The Shining Sea (2 page)

Authors: George C. Daughan

The heroic efforts of the American navy were critical in winning the war and the peace. Victory in the key battles at Plattsburgh, Baltimore, and New Orleans would have been impossible without the navy. It's true that the Battle of New Orleans was fought (on January 8, 1815) after the peace treaty had been signed at Ghent, on December 24, 1814. But the lopsided outcome at New Orleans showed the potential of American arms and had a major impact on Castlereagh. The navy's part in the battle is not well known, but the hero of the Battle of New Orleans, General Andrew Jackson himself, was the first to acknowledge that the tiny naval contingent played a key part in securing a tremendous victory.

The war revealed hidden strengths that made the small American fleet far more potent than its meager size would indicate. Several factors accounted for its surprising success. To begin with, the ships were as good as, and often better, than their British counterparts, and so were their crews. American men-of-war were manned by volunteers who were required to sign on for only two years, unlike British tars who were forced to serve until the war was over. American seamen exhibited an inspiring degree of patriotism, willingly enduring unbelievably harsh conditions. British seamen were patriotic, too, but their unusually high rate of desertion demonstrated, as nothing else could, how brutal conditions were aboard their ships. American desertions, by comparison, were minuscule. There were no impressed men aboard American men-of-war as there were in the Royal Navy. And the treatment of the crews was far better in the American fleet. Pay, health, food, and discipline were all superior.

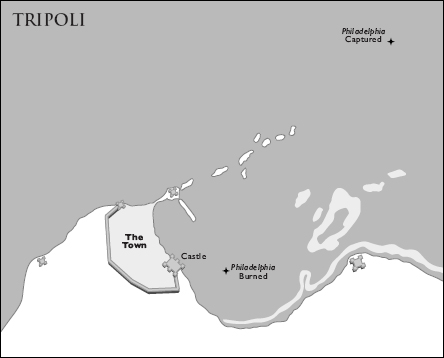

Perhaps the most important factor accounting for the success of the American navy was its superb officer corps. Unlike the army, which had not fought (except against small numbers of poorly armed Indians) since the Revolution, the navy's leaders were experienced fighters, having begun their baptism of fire during the Quasi-War with France from 1798 to 1800. Their skills were further honed during the war with Tripoli, which lasted from 1801 until 1805.

A strong naval tradition, dating back to the War of Independence, added to the navy's strength. Heroes like John Paul Jones, John Barry, Silas Talbot, and many, many others inspired the young officers. So, too, did their fathers and uncles who fought with distinction in the Continental and state navies during the Revolution. Lesser-known heroes, like Christopher Perry, Stephen Decatur Sr., George Farragut, and David Porter Sr. inspired their sons to follow in their footsteps. The navy's young stars also benefited from gifted mentors like Thomas Truxtun and Silas Talbot during the Quasi-War and Edward Preble during the war with Tripoli.

David Porter Jr. was among the navy's more promising young officers. He had joined the service in 1798 and had been in the thick of the fight during the Quasi-War and the war with Tripoli. When he sensed the War of 1812 coming, he wanted, more than anything else, to be a part of it.

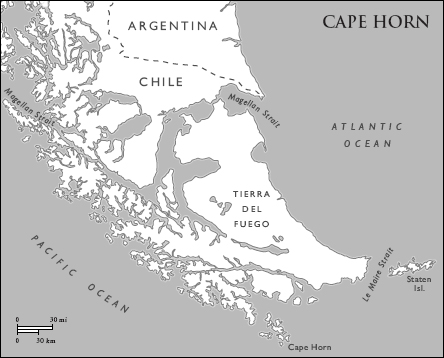

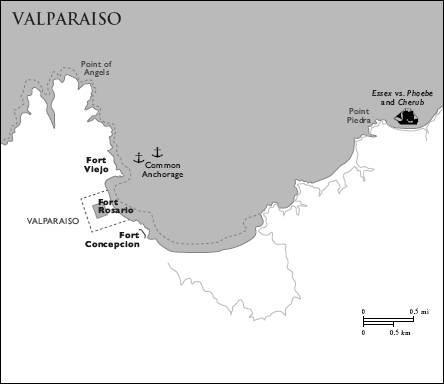

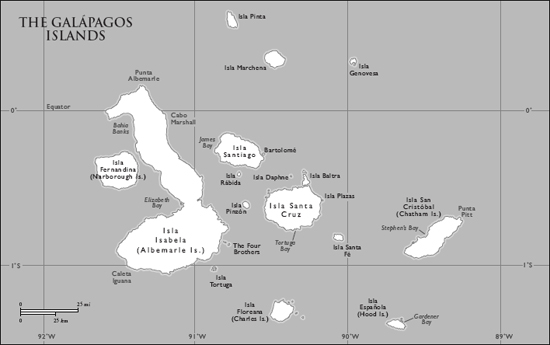

He viewed it as an opportunity to achieve everlasting fame, one that might never come again. His chance came early in the fighting, and he eagerly grasped it. Beginning in October 1812, he began a seventeen-month cruise in the USS

Essex

that would become the most famous voyage of the war, and one of the most spectacular in the entire age of fighting sail. What follows is the remarkable story of his unforgettable odyssey.

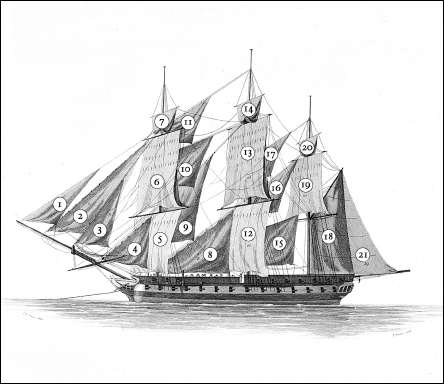

T

HE

S

AILS OF A

S

QUARE

-R

IGGED

S

HIP

1. Flying jib

2. Jib

3. Fore topmast staysail

4. Fore staysail

5. Foresail, or course

6. Fore topsail

7. Fore topgallant

8. Mainstaysail

9. Maintopmast staysail

10. Middle staysail

11. Main topgallant staysail

12. Mainsail, or course

13. Maintopsail

14. Main topgallant

15. Mizzen staysail

16. Mizzen topmast staysail

17. Mizzen topgallant staysail

18. Mizzen sail

19. Mizzen topsail

20. Mizzen topgallant

21. Spanker