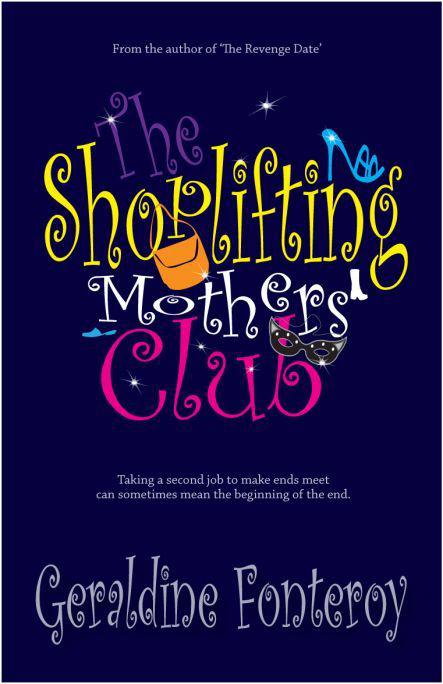

The Shoplifting Mothers' Club

Read The Shoplifting Mothers' Club Online

Authors: Geraldine Fonteroy

| The Shoplifting Mothers' Club | |

| Geraldine Fonteroy | |

| Furrow Imprint (2012) | |

| Rating: | ***** |

Sure, being married to a workaholic pro-bono lawyer and living in Surrey on pennies isn't ideal - particularly when the yummy mummies at school take every opportunity to point out the differences between their husbands' incomes and hers.

With their Range Rovers, size 6 skinny jeans and waist-length hair extensions, they couldn't be more different to Jessica and her own more 'herbal' approach to life.

But when eight-year-old Rachel suffers a life changing injury, and husband Ronald refuses to pay for a private surgeon, Jessica becomes intimately involved with the vacuous group from school, a decision that dramatically changes the course of the future for herself and her family.

The Shoplifting Mothers’ Club

By Geraldine Fonteroy © 2012

e-ISBN: 978-1-907504-32-7

Published by Furrow Imprint exclusively worldwide 2012

© All rights reserved in all media by Furrow Imprint.

This book is a work of fiction. Any similarities to any person, place or thing living or dead is entirely coincidental.

For the mini-llamas with love.

IT ALWAYS COMES down to money, grumbled Jessica Maroni to herself as she bundled another huge box of fairly useless home-brand washing powder into her trolley. No matter how many concessions one made to love, or the universe, or the spirits or whoever else was supposed to guide all the poor souls stuck permanently on this decaying planet, money always got in the way.

Take today, for instance. Jessica had to make cupcakes for Rachel to take to school for a fundraiser the next day. Problem was, in order for her husband Ronald to work as a pro-bono immigration lawyer, they were on a ridiculously tight budget. An extra five quid for cupcakes and icing meant that she had to think of something cheap for dinner, find a substitute for the kids’ favourite breakfast cereal, and choose a washing powder that would, in all probability, turn her whites grey.

‘Dear me, aren’t those trousers a tad tight?’ A cheerful voice interrupted the unhappy thoughts.

There behind her stood the ultimate yummy mummy of Berry Street Junior School, Chelsea Jordan. The pristine pair of white jeans, loose black and white top with tiny subtle sequins that gave a festive air to the outfit and a pair of killer heels indentified her as someone who didn’t frequent the cheaper supermarket chains. Attached to her arm was a handbag that looked to be worth more than Jessica and Ronald’s two cars put together. As usual, Chelsea wore a bucket load of orange makeup. Jessica could never understand why – the woman seemed to have perfect skin and reasonable taste. What was with all that gloop she plastered on every morning?

It was a question she wouldn’t bother asking, though. Ever since an unfortunate incident on the first day of primary school, when Jessica’s daughter Rachel had dropped a pot of paint directly into Chelsea’s daughter Sienna’s new D&G Mary Janes, Chelsea had hated Jessica and, because of the irrationality of it all, Jessica hated Chelsea. It was mutual detestation.

‘I’m surprised to see you here,’ Jessica said, looking away and feigning interest in the under-populated flour section.

Damn. Only the expensive stuff left.

Why won’t these places stock up the generic brands? Who wants to pay double, or triple for flour? The genetically-modified stuff was fine for her. Well, not fine, but it was better than nothing.

Chelsea smiled. ‘Actually, I’m here with my mother. Poor thing insists on

actually

coming to

this

supermarket.’ She wrinkled her nose, as one might at a putrid odour. ‘I told her that there are so many other ways of doing the shopping in this day and age. Take me, for example. I simply ask my maid to do it.’

Of course she does.

Jessica looked intensely at the two quid flour, hoping one of three things might happen – Chelsea would disappear; the generic brand would suddenly reappear on the shelf; or a large portion of the ceiling would cave in and flatten Chelsea. Option Three was preferable.

‘I don’t suppose Rachel is going to Paris in the half-term, is she?’ Chelsea observed her fingernails intently.

Was she joking? If they couldn’t afford flour, they couldn’t afford Paris.

‘What?’

‘You know, it’s for French class. Not compulsory, of course. But I believe most of the kids are going. Such a wonderful opportunity, don’t you think?’

Ah, that explains it.

Rachel had been moping around yesterday and despite Jessica taking her to the local park for an hour’s concentrated swinging, she had failed to cheer up. But why hadn’t the little girl told her what the problem was?

Because Ronald was always telling the kids not to waste money, that’s why.

‘I haven’t been availed of the details,’ Jessica said.

At least it was the truth.

‘Oh, the note went out with the kids day before yesterday. You know how eight year olds are, though. Probably find it in the bottom of Rachel’s bag.’

‘Probably.’

‘The Paris thing is quite expensive and the children are so young – it is a luxury to send them abroad just to practise the language, don’t you think?’

‘Yes, I suppose so.’

‘Of course, with everyone killing themselves to get into Madson Grammar in a few years, it all helps, doesn’t it? A little practice of the proper

lingo

won’t hurt, will it?’ Chelsea smiled sweetly. Jessica’s blood boiled. Chelsea could well afford to send Sienna to a private school, instead of taking up a place at the local grammar. Chelsea drove a Range Rover, had Caribbean holidays and sent her children to the local schools – no doubt so that she could guarantee she was top dog.

The two women stood, uncomfortable in each other’s presence. Feeling like the definite poor relation – brown frizzy hair, clothes that were at least five years out of fashion and ill-fitting thanks to recent weight gain; and a face devoid of makeup, Jessica nevertheless wasn’t going to be the one to break and run. She could hear Chelsea’s comment to the other bitch mothers at the school gates later:

Oh, poor thing, so embarrassed about how she looked, she just bolted.

It wouldn’t be the first time. There had been that meeting in Costa Coffee a couple of months ago. Her mate Elise had revealed that Jessica’s obvious avoidance of Chelsea had been the subject of much hilarity amongst the BIBs (Bitches in Burberry).

The seconds ticked by, and finally, Chelsea was paged. Her mother was clearly fed up with waiting for her.

‘Well, I suppose I should go and rescue Mum. Poor dear does hate these places, but won’t trust just anyone to do her shopping for her.’

‘Okay.’

Go away.

‘So, let me know if you’re going to do the Paris thing – we can carpool to Kings Cross or something.’

‘Yes, sure, will do.’

When hell freezes over.

Finally alone, Jessica sank back against the shelves.

Great

. Something else they couldn’t afford to do for their kids. First it was ballet and football lessons, then it was any sort of holiday and now this.

It was easy to gloss over the details, when you were young and in love; easy to believe in possibilities. Ronald certainly had, eventually forming his small practice to help those who were at risk of starvation, torture or death if deported. But then they had ended up living in poverty in one of the country’s most affluent areas. It wasn’t planned, but when an unrenovated wreck came on the market, spitting distance from Ronald’s office and the school, they’d overextended themselves on an interest-only mortgage and moved in.

Early on, when it was clear that Ronald’s salary wasn’t going to change for the foreseeable future, Jessica had wanted to move, but Ronald said that anywhere in the UK was expensive to live in – what was the point of paying out all that stamp duty and ending up worse off. She’d agreed, because she always deferred to her husband’s opinion, but as time went on, the sense of the argument was slowly eroding.

It was one thing to admire Ronald’s altruism at wanting to help the poor, but who was going to help them, Jessica wondered.

THINGS ONLY GOT WORSE when she arrived home to find that their youngest son Paul’s satchel schoolbag had been mutilated during an after-school play date with Elise’s son Zack.

‘Sorry,’ her friend said sheepishly. ‘Apparently they used it to create a swing. Didn’t quite work out. Paul banged his head and Zack’s got a huge gash on his arm. Rachel had the good sense to stay out of the whole silly affair.’

Over by the toybox in the nearby play alcove, Zack held up his arm in confirmation.

‘Oh.’ Jessica didn’t know what to say. Paul would be taking a plastic bag to school tomorrow.

‘Everything okay?’ Elise asked, as Jessica automatically flicked the switch on the kettle and reached for some cups. Shame they were all chipped. Elise and her husband weren’t exactly affluent, but they at least had matching cups. Still, the woman had drunk tea in her home a million times – no point worrying about the cups now, was there?

Offering her friend a seat, Jessica sighed. ‘The usual, money.’ A few minutes later, the tea was poured and the sorry tale of the Paris offering was revealed, as quietly as possible, in case Rachel was listening. Elise’s older daughter was in Year 7 at Madson Grammar, and Zack and Paul were too young to go to Paris, so she was in the dark about the trip.

‘How much is it?’

Shrugging, Jessica replied that if it was more than the price of a Coke, they couldn’t afford it.

‘Maybe you could get a job? Even part-time. That could make a difference, couldn’t it?’

‘I’ve looked. Anything that doesn’t cost a fortune in petrol to get to is for young kids, not someone my age. Even the coffee places want kids – they’re cheap and available.’

‘What did you do before the kids? Can you go back to that?’

Jessica had given up work as a legal secretary the moment Rachel was born. Things had changed a lot in nine years, and by the time they paid for after school care and transport, the lowly job she was qualified for wouldn’t be worth the effort. ‘Besides, I worry about the kids – what if they need me and I’m not here?’

‘How about something from home? Childminding?’

‘I couldn’t, not with Dad ill.’ Jessica’s father had recently been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and she’d promised her mother she’d be available if she was needed. Her parents still lived in the family home on the Isle of Wight, hours away from their home in the small Surrey village of Clawson.

‘I still don’t get how a lawyer can make so little.’ Elise finished her cup and stood to make another. ‘Every single one I’ve come across is rolling in it. My friend had to get a non-molestation order the other week – cost her two and a half grand.’

Shamefully, Jessica couldn’t help but think:

there goes my cuppa in front of the telly later.

There were only two teabags left, and she hadn’t been able to afford a new box, not with the expensive brand name flour she’d had to buy. ‘He works for a charity. Almost for free.’

‘Oh, well can’t your parents help out again?’

Jessica didn’t want to reveal too much about her finances, but Elise knew that the Drummonds had paid for a good portion of the Maroni home in order to bring the mortgage payments right down to an affordable level when Rachel was born.

‘They’ve already done so much, and now with Dad so ill, I can’t really ask.’

Pouring the water, Elisa shook her head. ‘You can’t keep going like this. Tell Ronald he needs to get a proper job. It’s nuts, you living like this with two kids.’

‘How can I? He loves that job. It was the only reason he studied law, remember? It’s his life plan.’

‘What about your life plan? Things change, Jess. Kids grow up and want to go to Paris. Everyone has to adapt.’