The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent (24 page)

Read The Siege of Vienna: The Last Great Trial Between Cross & Crescent Online

Authors: John Stoye

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire

Next day the bombardment paused towards the evening, when rain fell. During the lull the defence brought up new, and removed faulty, guns on the bastions; but at the same moment some citizens were shuddering over the

rumour that enemy soldiers were creeping up a sewer. Others boldly re-opened their shops, closed during the day. Others again went to church; and in St Stephen’s the congregation and preacher were startled by a ball which burst into the building and struck the organ.

On Sunday the Turks at last exploded their mine opposite the ravelin. It knocked down part of the palisading, and ‘volunteers’ poured into the attack while the garrison rallied to drive them out. It was a serious moment, and a number of high-ranking officers were wounded before the enemy moved back to the shelter of their trenches. In fact this assault set a pattern for a whole series of explosions, attacks and counter-attacks in the course of the following week. The other novel element, introduced on 26 July, was the countermining of the defenders, an art which they only mastered gradually. A few bold improvisers had offered their services to Starhemberg, especially Captain Hafner of the City-Guard, but they needed practice and experience before becoming efficient. The garrison relied more on their artillery, and on the bombs or grenades which they threw from the counterscarp into the Turkish works and the Turkish squads of labourers. On 27 July, at last, some attackers jumped into the covered way opposite the Burg, but were promptly thrown down into the moat and slaughtered by Christian troops at this lower level. On every one of three days following, the battle was furious. Inch by inch the Turks broke down the defences of the counterscarp. The effect of their bombs was to destroy the palisading, and after an expensive counterattack had managed to drive back the troops which stormed in after the explosions, it was necessary on each occasion to repair the breach with more timber and fresh digging; but a stage had now been reached when these outer works could no longer be strengthened, and they could only be patched with great difficulty. It seems premature, but Starhemberg was already at this time making arrangements to fight inside the walls. He listed assembly-points for the burghers and other untrained forces, he silenced all bells and chimes except for the striking of the hour from the church towers, he decreed that the great bell of St Stephen’s should only sound to summon the citizens if the worst of all emergencies should befall and the Turks entered the city.

Occasionally there was good news. The Danube rose a little, which made an attack across the Canal less likely. A large band of students from the University and men from the corps of butchers once sallied from the defences into the open country and brought back cattle; fresh meat had been getting scarce and dear. Unfortunately dysentery spread fast among the troops and civil population. It was the Turks’ strongest ally. The town council set aside the Passauerhof, the property of the Bishop of Passau, as a hospital for these patients. The military authority, anxiously totting up the losses caused by mining and storming, now saw them multiplied by this new factor, and began to look around for reserves. The companies of ‘Hofbefreiten’ were deployed for the first time, and posted to the ravelin by the Stuben-gate. It was not a post of great significance, but they freed better soldiers for use elsewhere. This

was the period of Vienna’s greatest isolation. Starhemberg, from 24 July to 4 August, was in touch neither with Kuniz nor Lorraine. It hardly mattered, provided that the Turks continued to stand in front of, and not in or under the counterscarp. The defenders of the city also pinned their hopes to earlier reports that a relieving army would arrive in Austria in the fairly near future, and they still enjoyed plentiful supplies of bread and cash. The troops had been paid punctually, and large quantities of corn were ground. But if disease continued to spread and stocks dwindled and the enemy advanced, which all appeared probable, then the morale of even the commanding officer was vulnerable. The inveterate pessimism of Caplirs would prove as infectious as a bout of plague.

On 31 July the Christian forces listened to their own bands making excellent music, so they said, with drum and pipe. In the Turkish camp the Sultan’s special envoy Ali Aga took his leave of the Grand Vezir before returning to Belgrade, and the Turkish musicians were also commanded to strike up.

20

The accounts of the besiegers and the besieged serve to show that the enemy’s music roused scorn on both sides, while each continued to fight desperately in front of the Vienna Burg. Every foot of this small area was disputed, in the first week of August as in the last week of July. The Turks, having brought their foremost trenches as far as the palisades guarding the counterscarp, now threw up the earth to such a height that they gradually raised themselves sufficiently to command a partial view of the defence works, while at the same time they also tunnelled underneath their own entrenchments. They tried to set fire to the timbers which barred them, and the garrison countered by taking water from the ditch in the moat to put out the fires. Arrows and grenades flew about, as well as bombs and balls and stones. The Christians sometimes fixed scythes to long poles, to strike at the enemy through the palisades. On 2 August for the first time Starhemberg’s men sprung a mine effectively, to the heartfelt satisfaction of the commander who congratulated the officer in charge, Captain Hafner. Arms and legs mingled with the smoke and falling rubbish opposite the Löbel-bastion. Artillery fire normally dominated the forenoon, while in the afternoon and during the earlier part of the evening the mines were exploded, to be followed by one or more assaults immediately afterwards and in the course of the night. At night, too, repair work was carried out by both sides. The Turks began to get into the defences on the counterscarp opposite the Burg-ravelin, because here their tunnelling and their mines had practically obliterated the angles and entrenchments which alone made effective resistance possible. Misdirected countermines at a critical time had even helped them. By the night of 3 August they were at last fairly in control at this point; and a new phase of the siege began when they started shooting down the ditches in the moat on both sides of the ravelin opposite them. The most desperate attacks failed to drive them back, and Habsburg losses were very heavy. One of the most serious was the death in action of Rimpler the engineer. The defenders, retreating from the lost section of the

counterscarp, tried to bring back the timbering of the palisades with them, or to burn it; while the Turks dug and mined in such a way that earth fell from the counterscarp into the moat and partially filled it up. Their intention, naturally, was to raise a barrier protecting them from the marksmen posted in the ‘caponnières’ recently constructed to left and right of the ravelin, and so to ease their progress towards the ravelin itself. This obstacle required an assault at various levels, with miners attaching themselves to its base while storm troops mounted as near as they could get to the top of the outside walls.

This descent into the moat, and then the move forward as far as the ravelin, cost the Turks nine more days of furious fighting. While they piled up their earthworks, Starhemberg’s men managed to come along with barrows and trundled earth away. Then the Turks would sally out from their cover in great force, and the garrison came out likewise to repulse them. The Turks dug galleries and boarded them over; in the night of 8 August Daun and Souches with 300 men set fire to some of these galleries. On the 9th, the Turks destroyed a wall connecting one corner of the ravelin with the Burg-bastion. On the 10th they sprung a new mine at the forward point of the ravelin, but it misfired and they had to begin again. The losses on both sides were very severe and, as officers fell, promotion was rapid. In Vienna a new graveyard was opened in the old cemetery of the Augustinians. While one popular officer, Kottoliski, died on the Löbel side of the ravelin, his brother was wounded on the other side in the course of the same night’s fighting.

21

The Turks continued to work forward into the counterscarp opposite the bastions, and from the counterscarp into the moat. The cannon from the bastions played on the batteries which the Turks themselves gradually moved forward; bombs sometimes exploded on guns opposite, and fired them off. Yet the brunt of the fighting was in the central position, at the forward tip of the ravelin. The garrison had at length to withdraw its heavier pieces from this area to the main city wall and to the bastions; but at the same time, along the stoutly protected causeway which led forward from the wall to the rear of the ravelin, detachments of troops periodically advanced to mount guard—one detachment relieving another at fixed intervals—in that crucial, most exposed of all positions. As long as possible, also, they held on to points in this section of the counterscarp, and to the caponnières in the moat. Slowly they were forced out. The Turks edged in, were pushed back, and edged forward again. The interminable rota of watches in the ravelin still continued.

The monotony, as always in crises of this kind, matched the suspense. It was difficult to distinguish one mine, one sortie, from others. But in the early afternoon of 12 August, since nothing of note had occurred earlier in the day, something serious was expected. The officer commanding in the ravelin was warned by his men that they could not locate the spot where the Turks were obviously preparing their next mine on the grandest scale. As a spectator observed, even the attackers seemed to pause and wait anxiously. Then, abruptly, the mine was sprung. It was said to have shaken half the town.

When the smoke cleared, the same spectator was horrified to see that the combined result of previous Turkish works and the new upheaval was to raise a sort of causeway to the level of the defenders’ first entrenchment on the ravelin, wide enough for fifty attackers abreast. Soon eight Turkish standards were fixed there. The fighting was intense; the garrison recovered some of the ground lost, but at the end of the day Starhemberg had to recognise that his opponents now held a small part of their immediate objective, the ravelin, and could not be driven off. The 12th of August, like the 3rd, was an epoch in the siege of Vienna.

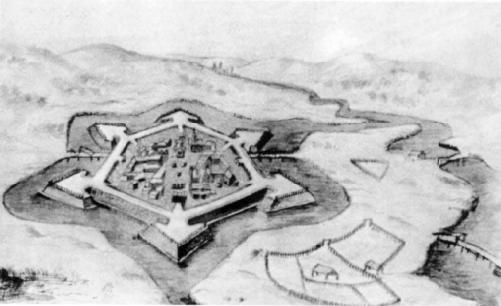

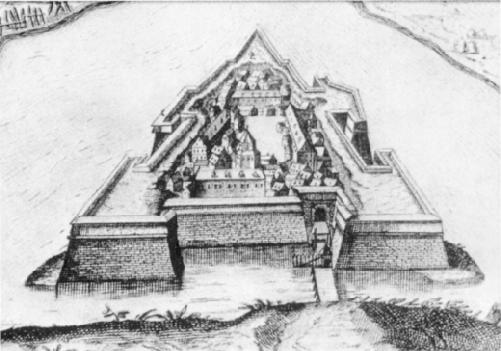

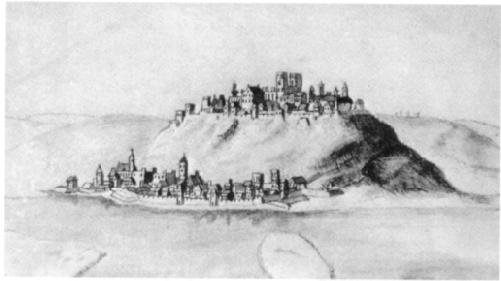

I. The Ottoman Frontier:

above,

Esztergom;

below

Neuhäusel

Edward Browne, the English traveller who made these pen-and-ink sketches in 1669, wrote a few years later of the frontier between Christendom and Islam in Hungary:

A man seems to take leave of our world when he hath passed a day’s journey from Rab (Györ) or Comorra (Komárom): and, before he comes to Buda seems to enter upon a new stage of the world, quite different from that of western countries: for he then bids adieu to hair on the head, bands, cuffs, hats, gloves, beds, beer: and enters upon habits, manners and a course of life which, with no great variety but under some conformity extend unto China and the utmost parts of Asia