The Signature of All Things (66 page)

Read The Signature of All Things Online

Authors: Elizabeth Gilbert

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Foreign Language Fiction

Then she was underwater again, knocked over by three women who were attempting to run over her. They succeeded: they ran over her. One of them pushed off Alma’s chest with her feet—using Alma’s body for leverage, as one would use a rock in a pond. Another kicked her in the face, and now she was fairly certain her nose was broken. Alma struggled again to the surface, fighting for breath and spitting out blood. She heard somebody call her a

pua‘a—

a hog. She was pushed under again. This time, she felt sure it was intentional; her head had been shoved down from the back by two strong hands. She surfaced once more, and saw the ball fly past her. She dimly heard the cheers of the crowd. Again, she was trampled. Again, she went under. When she tried to surface this time, she could not: somebody was actually sitting on her.

What happened next was an impossible thing: a complete halting of time. Eyes open, mouth open, nose streaming blood into Matavai Bay, immobilized and helpless underwater, Alma realized she was about to die. Shockingly, she relaxed. It was not so bad, she thought. It would be so easy, in fact. Death—so feared and so dodged—was, once you faced it, the simplest thing going. In order to die, one merely had to stop attempting to live.

One merely had to agree to vanish. If Alma simply remained still, pinned beneath the bulk of this unknown opponent, she would be effortlessly erased. With death, all suffering would end. Doubt would end. Shame and guilt would end. All her questions would end. Memory—most mercifully of all—would end. She could quietly excuse herself from life. Ambrose had excused himself, after all. What a relief it must have been to him! Here she had been pitying Ambrose his suicide, but what a welcome deliverance he must have felt! She ought to have been envying him! She could follow him straight there, straight into death. What reason did she have to claw for the air? What point was in the fight?

She relaxed even more.

She saw pale light.

She felt invited toward something lovely. She felt summoned. She remembered her mother’s dying words:

Het is fign

.

It is pleasant.

Then—in the seconds that remained before it would have been too late to reverse course at all—Alma suddenly knew something. She knew it with every scrap of her being, and it was not a negotiable bit of information: she knew that she, the daughter of Henry and Beatrix Whittaker, had not been put on this earth to drown in five feet of water. She also knew this: if she had to kill somebody in order to save her own life, she would do so unhesitatingly

.

Lastly, she knew one other thing, and this was the most important realization of all: she knew that the world was plainly divided into those who fought an unrelenting battle to live, and those who surrendered and died. This was a simple fact. This fact was not merely true about the lives of human beings; it was also true of every living entity on the planet, from the largest creation down to the humblest. It was even true of mosses. This fact was the very mechanism of nature—the driving force behind all existence, behind all transmutation, behind all variation—and it was the explanation for the entire world. It was the explanation Alma had been seeking forever.

She came up out of the water. She flung away the body on top of her as though it were nothing. Nose streaming blood, eyes stinging, wrist sprained, chest bruised, she surfaced and sucked in breath. She looked around for the woman who had been holding her under. It was her dear friend, that fearless giantess Sister Manu, whose head was scarred to pieces from all the various awful battles of her own life. Manu was laughing at the

expression on Alma’s face. The laughter was affectionate—perhaps even comradely—but still, it was laughter. Alma grabbed Manu by the neck. She gripped her friend as though to crush her throat. At the top of her voice, Alma thundered, just as the Hiro contingent had taught her:

“OVAU TEIE!

TOA HAU A‘E TAU METUA I TA ‘OE!

E ‘ORE TAU ‘SOMORE E MAE QE IA ‘EO!”

THIS IS ME!

MY FATHER WAS A GREATER WARRIOR THAN YOUR FATHER!

YOU CANNOT EVEN LIFT MY SPEAR!

Then Alma let go, releasing her grip on Sister Manu’s neck. Without a moment’s hesitation, Manu howled back in Alma’s face a magnificent roar of approval.

Alma marched toward the beach.

She was oblivious to everyone and everything in her midst. If anyone on the beach was either cheering for her or against her, she could not possibly have noticed.

She came striding out of the sea like she was born from it.

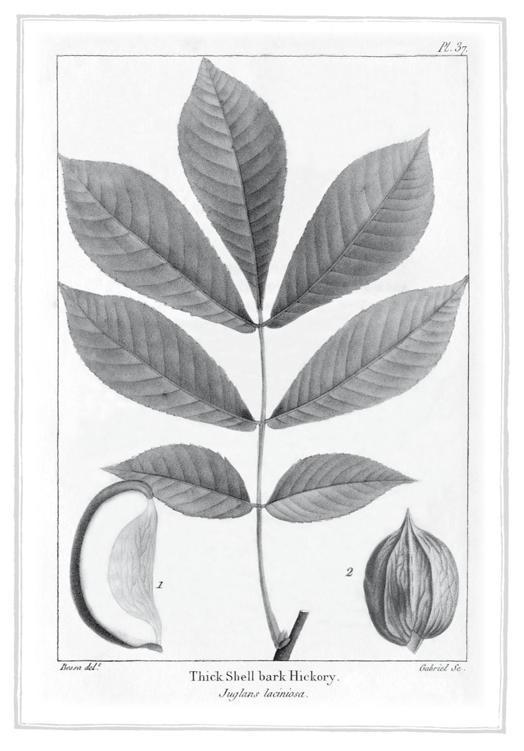

Juglans laciniosa

PART FIVE

The Curator of Mosses

Chapter Twenty-seven

A

lma Whittaker arrived in Holland in mid-July of 1854.

She had been at sea for more than a year. It had been an absurd voyage—or, rather, it had been a

series

of absurd voyages. She had departed Tahiti in mid-April the year before, sailing on a French cargo ship heading to New Zealand. She had been forced to wait in Auckland for two months before she found a Dutch merchant ship willing to take her on as a passenger to Madagascar, whence she’d traveled in the company of a large consignment of sheep and cattle. From Madagascar, she’d sailed to Cape Town on an impossibly antique Dutch

fluyt

—a ship that represented the finest of seventeenth-century maritime technology. (This had been the only leg of the voyage where, in fact, she truly feared she might die.) From Cape Town, she had proceeded slowly up the western coast of the African continent, stopping to change vessels in the ports of Accra and Dakar. From Dakar, she’d found another Dutch merchant ship heading first to Madeira, then up to Lisbon, across the Bay of Biscay, through the English Channel, and all the way to Rotterdam. In Rotterdam, she had purchased a ticket on a steam-powered passenger boat (the first steamer she’d ever been on), which carried her up and around the Dutch coast, finally heading down the Zuiderzee to Amsterdam. There, on July 18, 1854, she disembarked at last.

Her journey might have been both swifter and easier if she’d not had Roger the dog along with her. But she did have him, for when the time had

come to leave Tahiti at last, she’d found herself morally incapable of leaving him behind. Who would take care of unlovable Roger, in her absence? Who would risk his bites, in order to feed him? She could not be entirely certain that the Hiro contingent would not eat Roger once she was gone. (Roger would not have made for much of a meal; nonetheless, she could not bear to imagine him turning on a spit.) Most significantly of all, he was Alma’s last tangible link to her husband. Roger had probably been there in the

fare

when Ambrose had died. Alma imagined the constant little dog standing guard in the center of the room during Ambrose’s final hours, barking out protection against ghosts and demons and all the attendant horrors of extraordinary despair. For that reason alone she was honor bound to keep him.

Unfortunately, few sea captains welcome the company of woebegone, hunchbacked, unfriendly little island dogs on their ships. Most had simply refused Roger, and thus sailed on without Alma, delaying her journey considerably. Even when they had not refused, Alma sometimes had been required to pay double fare for the privilege of Roger’s company. She paid. She sliced open yet more hidden pockets in the hems of her traveling dresses, and pulled out yet more gold, one coin at a time. One must always have a bribe.

Alma did not mind the onerous length of her journey, not in the least. In fact, she needed every hour of it, and had welcomed those long months of isolation on strange ships and in foreign ports. Since her near-drowning in Matavai Bay during that raucous game of

haru raa puu

, Alma had been balancing on the keenest edge of thought she had ever experienced, and she did not want her thinking disturbed. The idea that had struck her with such force while she was underwater now inhabited her, and it would not be shaken. She could not always identify whether the idea was chasing her, or whether she was chasing it. At times, the idea seemed like a creature in the corner of a dream—drawing closer, then vanishing, and then reappearing. She pursued the idea all day long, in page after page of scrawling, vigorous notes. Even at night, her mind tracked the footsteps of this idea so relentlessly that she would awaken every few hours with the need to sit up in bed and write more.

Alma’s greatest strength was not as a writer, it must be said, although she had already authored two—nearly three—books. She had never claimed literary talent. Her books on mosses were nothing that anyone would read

for pleasure, nor were they even exactly

readable

, except to a small cadre of bryologists. Her greatest strength was as a taxonomist, with a bottomless memory for species differentiation and a bludgeoningly relentless capacity for minutiae. Decidedly, she was no storyteller. But ever since fighting her way to the surface that afternoon in Matavai Bay, Alma believed that she now had a story to tell—an immense story. It was not a cheerful story, but it explained a good deal about the natural world. In fact, she believed, it explained everything.

Here is the story that Alma wanted to tell: The natural world was a place of punishing brutality, where species large and small competed against each other in order to survive. In this struggle for existence, the strong endured; the weak were eliminated.

This in itself was not an original idea. Scientists had been using the phrase “the struggle for existence” for many decades already. Thomas Malthus used it to describe the forces that shaped population explosions and collapses across history. Owen and Lyell used it as well, in their work on extinction and geology. The struggle for existence was, if anything, an obvious point. But Alma’s story had a twist. Alma hypothesized, and had come to believe, that the struggle for existence—when played out over vast periods of time—did not merely

define

life on earth; it had

created

life on earth. It had certainly created the staggering variety of life on earth. Struggle was the mechanism

.

Struggle was the explanation behind all the most troublesome biological mysteries: species differentiation, species extinction, and species transmutation. Struggle explained everything.

The planet was a place of limited resources. Competition for these resources was heated and constant. Individuals who managed to endure the trials of life generally did so because of some feature or mutation that made them more hardy, more clever, more inventive, or more resilient than others. Once this advantageous differentiation was attained, the surviving individuals were able to pass along their beneficial traits to offspring, who were thus able to enjoy the comforts of dominance—that is, until some other, superior, competitor came along, or a necessary resource vanished. During the course of this never-ending battle for survival, the very design of species inevitably shifted.

Alma was thinking somewhat along the lines of what the astronomer William Herschel had called “continuous creation”—the notion of something both eternal and unfolding. But Herschel had believed that creation

could be continuous only at the scale of the cosmos, whereas Alma now believed that creation was continuous

everywhere

, at all levels of life—even at the microscopic level, even at the human level. Challenges were omnipresent, and with every moment, the conditions of the natural world changed. Advantages were gained; advantages were lost. There were periods of abundance, followed by periods of

hia‘ia

—the seasons of craving. Under the wrong circumstances, anything was capable of extinction. But under the right circumstances, anything was capable of transmutation. Extinction and transmutation had been occurring since the dawn of life, were still occurring now, and would continue to occur until the end of time—and if that did not constitute “continuous creation,” then Alma did not know what did.

The struggle for existence, she was certain, had also shaped human biology and human destiny. There was no better example, Alma thought, than Tomorrow Morning, whose entire family had been annihilated by unfamiliar diseases brought upon them by the Europeans’ arrival in Tahiti. His bloodline had

nearly

been rendered extinct, but for some reason Tomorrow Morning had not died. Something in his constitution had enabled him to survive, even while Death had come harvesting with both hands, taking all others around him. Tomorrow Morning had endured, though, and had lived to produce heirs, who may even have inherited his strengths and his extraordinary resistance to illness. This is the sort of event that shapes a species.