The Silent Boy (6 page)

Authors: Lois Lowry

"And Mattie Washington," he added. "You must know her, Naomi. Her house is close to yours."

Naomi, still at the stove, nodded. "She doesn't have pain, does she?"

"No," Father told her. "But I want to be sure she's being kept comfortable. She'll go soon."

"Ninety-two," Naomi said. "Seven children, only three still left, and one of them was always worthless."

Father smiled. "Even the worthless one is at her side. And lots of grandchildren."

"And some greats," Naomi told him. "I believe she has some greats."

"Yes. She's lived a good long life." Father pulled his heavy coat on. We could hear the horses in front; Levi had brought them around. They stamped their feet, and the bells on their

harnesses jingled. Horses like snow. It makes them excited, and I think they like the way their snorts make steam in the cold air. When Father opened the front door, I could hear one of them whinny. The light sliced into the hall when the door opened. The entire day was white, and I could see the flakes still drifting.

"The steps will be slippery, Henry. Be careful," Mother warned him, and then he was gone.

Â

The steps

were

slippery, I found, when finally, bundled up, mittened, and booted, with a red knitted scarf wrapped twice around my neck and up over my chin, I went outside. Next door, Austin was already out, building a snowman in his front yard for his sister, Laura Paisley, who even at two and a half had learned how to command her brother.

"Make him a nose!" Laura Paisley called from the front porch, where she watched Austin at work. Her own nose and cheeks were pink with cold. She was wearing blue mittens.

"I will," Austin promised. "First I have to finish him." He was still patting the sides smooth, and I went over to help. It was hard, walking through the snow, which was up partway to my knees. On the way, I broke off two thin branches from the forsythias to use as snowman arms.

"Ding-dong!" Laura Paisley shouted suddenly, clapping her mittened hands in delight.

Bells! Not like the small jingles from our two horses harnessed to the buggy. But many bells, rows of them, because the snow-roller had come around the corner and entered our street, with its six huge horses. Slowly, dragging the heavy roller, they flattened the snow in the street. When Father left, Orchard Street was like a meadow, or a sea of snow, not a street at all. Jed and Dahlia had pranced through, lifting their feet high, leaving prints of their spiked winter shoes in the deep new snow. But now Orchard Street was reappearing. And in front of each house, now, men and boys were out with shovels, clearing the walks.

The Stevensons hired girl came out onto their porch and took the frozen tea towels down. I thought she had been scolded. Her face was glum. But then she looked over, saw our snowman, and smiled. "Need a carrot?" she called. "I'll bring one out in a bit. And some lumps of coal for eyes."

Like our Peggy and Peggy's sister Nell, she was just a young girl, in from the farm, sending the money back home, to help out.

They were all slightly younger than Austin's brother, Paul Bishop, who would graduate next year from high school. Watching her unpin the towels, I wondered if she ever wished she could have stayed in school, studying French and

algebra, instead of washing tea towels and scrubbing the kitchen floor for the Stevensons.

Nellie came out to check on Laura Paisley, and behind her came Paul, who was home because the high school had also closed for the day. "Katy," Nell called to me, "ask your mother can Peggy come out just for a bit. Mrs. Bishop said I could!" Nell had a bright pink scarf wrapped around her neck, and her cheeks were pink, too, from the cold. Paul scraped some snow from the porch rail and made as if to put it down her neck, and Nell shrieked, as he wanted her to, and hunched her shoulders against him, laughing. Paul often teased Nellie till she giggled and blushed. Once, in the fall, when she was hanging sheets on the line in their backyard, I saw Paul come up behind her and put his face suddenly right into her hair. He tickled her with his nose against her neck and slid his arm around her waist. She had to wrestle him away, but she was laughing.

"We'll go sledding!" Paul called to Austin and me.

"Bundle up," Mother said when I went in for Peggy, "and don't stay out too long. Peg, you bring her home by lunchtime, and see that your sister doesn't let that little Laura Paisley get too cold!"

"Or Austin," I reminded my mother. "Nell must watch out for him, too."

"

Boys,

"Mother said, laughing. "Austin and Paul

can watch out for themselves, I imagine."

My friend Jessie Wood appeared at her corner, dragging her sled, and off we went, the group of us, to the hill beyond the Presbyterian church, pulling our sleds behind us, Laura Paisley perched on one and giggling as she bumped along. Everywhere were children and sleds in the new-rolled streets; and we could hear the jingle of sleigh bells as horses trotted by, pulling runnered cutters instead of the buggies that they were accustomed to. They tossed their heads and snorted steam.

"Did you go sledding when you lived at home, Peggy?" I asked. She was walking beside me, holding my hand.

"We didn't have sleds," she explained. "But we sat on cooking tins and slid down the hill. They whirled us all about."

"Nellie too? And Jacob?"

"Nellie did till she moved in to town. And once I held Anna in my lap and slid. But Jacob never, though he watched. I think he don't like the fastness."

"I don't, either," I confessed. "I just like the little hills."

"Katy's a fraidy-baby," Jessie said. "No, I'm not," I replied, but I knew it was true that I was.

"Ride with me, Katy, and try the big hill," Peggy

offered. "I'll hold you tight, I promise. It's a treat, full-speed. And the boys, they'll call you scaredy-cat if you don't."

So I did. Peg was strong and sturdy, and I wasn't frightened with her arms tight around me. I sat in front of her, on her long wool skirt. She pulled the guide rope up on either side, put her feet firm against the steer board, and we pushed off and sailed, both of us shrieking laughter all the way to the bottom of the hill, where we had to turn sharp to miss a tree. Then we stood there and watched as the others came down: Austin on his own, belly-whopping, and Jessie, too, lying on her sled and laughing as she flew by. Finally Paul and Nellie flew past together with Laura Paisley wedged in between. But Laura Paisley was fearful and cried. So Peggy and I took her to the babies hill and left Nell and Paul on their own.

On the gentle slope Laura Paisley wasn't frightened. Peggy sent her down again and again, and I waited at the bottom to haul her back up. From there, we could hear Austin hollering as he sped down the big hill, and I could see Jessie go just as fast and call out just as loud. Now and then we heard Nellie call out, too, in delight. Looking over from where I stood, I could see her bright pink scarf fly in the wind as Paul, behind her on the sled, steered the two of them down, slicing a turn at the bottom each time. The tree at the bottom

loomed like a danger, but all the sledders knew how to make the turn at just the right instant.

"Push me!" Laura Paisley begged, so Peg would give her a gentle shove and watch as she slid slowly and then tumbled, giggling, from the little sled at the bottom of the gentle slope.

Going home for lunch, I think we were all like the horses, excited and prancing. Nell, especially, was like a wild thing let loose; she teased and shouted and her voice was so shrill that Peggy murmured "Shhhh" to her in embarrassment at what others might think. But Nellie turned away with an irritated shrug and went to walk with Paul.Shedidn 't care what others thought.

Nell came over to visit her sister late on a sleety Thursday afternoon. They both had Thursday off, and usually Peggy went to the library that day, often taking me with her; she said she didn't mind. Nellie always went to town, to the pictures or the shops.

But today it was too cold and wet to walk far. Nellie was in a foul mood when she came over. She pulled off her coat and boots in the kitchen and unwound the scarf from her thick, damp hair. She had had other plans, she said, but the weather made her plans fall through.

Together the sisters went up to Peggy's third-floor room. Sometimes Peg let me go up there and visit when she had free time, but I could tell she didn't want me tagging along now. She and Nellie were chattering about grown-up girl things, and from my room below I could hear Nell's whoops of laughter and Peggy's quieter, more serious voice.

"They want to be by themselves," I complained to Mother, feeling left out.

She was in the little room at the end of the upstairs hall, the one we called "the sewing room" though no one ever sewed there. Mother was at the pine table with an album open on it, and she was carefully pasting things in what she called a "memory book." It was where the postcard of Niagara Falls was, and the newspaper account of Mother and Father's wedding. A dried and flattened flower was attached to one page, with a note in Mother's careful penmanship describing a tea party where a vase of pink roses had been part of the decoration. It was hard to imagine the brown faded thing as one of those roses.

Mother listened for a moment to the noises from Peggy's bedroom. She smiled. "I'm glad we got the quieter of the Stoltz sisters," she said. "Mrs. Bishop says that Nellie's a good worker but she has a very frivolous side."

"What's

frivolous?

"

"Silly."

"I don't think Nell is silly. She's very serious about wanting to be in pictures."

Mother raised an eyebrow. I knew she disapproved of the pictures, and I was sorry I had mentioned it. "What's that?" I asked, and pointed at a wisp of hair gathered and tied with a ribbon and attached to the page.

"That's yours, Katy," Mother said, looking at it fondly. "You were two years old and I trimmed your hair. You didn't have a lot, but it was in your eyes until I snipped it back.

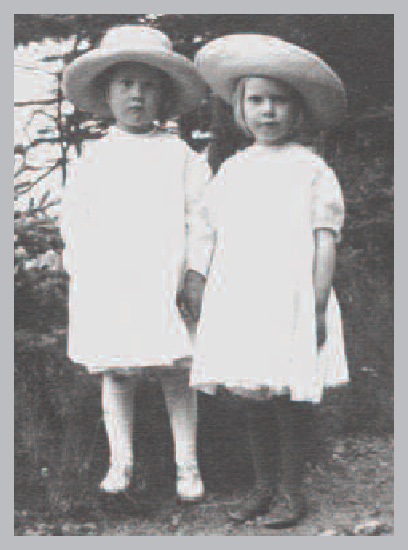

"And look at this!" She pointed to a picture. "You might remember this. You and Jessie Wood were both four that summer, and Jessie's father had a new camera."

I peered at the photograph of two solemn little girls, side by side, wearing hats, and gradually I remembered that day at the lake. It was summer. It came to me in fragments, in little details.

Jessie had black shoes, and mine were white.

The air smelled like pine trees.

A cloud was shaped like my stuffed bear. Then its ears softened and smeared, and it was just a cloud, really, not a bear at all (I knew it all along); then, quickly, the cloud itself was gone and the sky was only blue.

And there were fireworks! We were visiting at

the Woods' cottage there. Cottage sounded like a fairy tale: a woodcutter's cottage. Hansel and Gretel and their cottage.

But the Woods' cottage was not a fairy-tale storybook one. It was just a house. They invited my family to come to their cottage for the holiday called Fourthofjuly, which I didn't understand, and for fireworks.

I remembered the scent, the sky, the heat, the wide-brimmed straw hats we wore to protect our faces from the sun, and the white shoes and black. The shoes and stockings and dressesâeven the hatsâwere removed, at some point, because my memory told of Jessie and me, wearing only our bloomers, wading at the edge of the lake. We chased tiny silvery fishâminnows! Someone told us they were called minnows, and we said that to each other, laughing: "Minnows! Minnows!"

After a while we were shivering, even though the day was hot. My fingertips were puckered, pale lavender. Our mothers rubbed us dry with rough towels. Jessie fretted because there were pine needles stuck to her damp feet. We played in the sand at the edge of the lake.

The parents sat on the porch, talking, while Jessie and I amused ourselves, still half-naked in the sunshine, digging with bent tin shovels in the damp sand. Jessie had a pail and I didn't. I pretended that I didn't care about her pail,

though secretly I wished it were mine, with the bright painted picture printed on its metal side: pink-faced children building castles, green-blue water, foamed with white, curling behind them.

Stealthily I followed a beige toad that hopped heavily away into tall grasses edging the small beach. Soon I could no longer see the toad (I had begun to think of him as "my" toad) but when I waited, silent, I saw the grass move and knew that he had hopped again. I waited, watched. I followed where the grass moved. It was taller than my head, now, and I was surrounded by it and was briefly frightened, feeling that I had become invisible and not-there with the high reeds around me. But the world continued to be close by. I could hear the grownups talking on the porch, still.

"Where's Katy?" I heard my mother ask, suddenly.

"Jessie, where did Katy go?" Mrs. Wood called in an unconcerned voice.

"I don't know." Jessie's voice was not that far away from me.

"She was right there. I saw her just a minute ago." That was my father's voice.

"It's amazing, how quickly they scamper off, isn't it?" Mrs. Wood again. She was using a cheerful voice, but I could tell that now she was worried, and I was made pleased and proud by the worry.