The Silk Road: A New History (5 page)

Read The Silk Road: A New History Online

Authors: Valerie Hansen

Thina? The spelling makes sense, given that ancient Greek had no letter for the sound “ch” and the letter theta was probably pronounced something like

ts

in ancient Greek. The author did his best to record the unfamiliar name he heard from Indian traders. In Sanskrit, China was pronounced Chee-na (named for the Qin dynasty, 221–207

BCE

); the Sanskrit word is the source of the English word “China.” In subsequent centuries, Roman geographers like Ptolemy (ca. 100–170

CE

) learned more about Central Asia, but scholars are still struggling to reconcile their descriptions with the actual geography of the region.

34

The author of the

Periplus

is certain of only one kernel of information about the Chinese: they produced silk in the form of floss from cocoons, spun thread from that floss, and wove cloth from the thread.

The Chinese were indeed the first people in the world to make silk, possibly as early as 4000

BCE

, if an ivory carving with a silkworm motif on it, from the Hemudu site in Zhejiang, constitutes proof of silk manufacture. According to the Hangzhou Silk Museum, the earliest excavated fragment of silk dates to 3650

BCE

and is from Henan Province in central China.

35

Skeptical of such an early date, experts outside of China believe the earliest examples of silk date to 2850–2650

BCE

, the time of the Liangzhu culture (3310–2250

BCE

) in the lower Yangzi valley.

36

In the first century

CE

, when the

Periplus

was written, the Romans did not know how silk was made. Pliny the Elder (

CE

23–79) reported that silk cloth had made its way to Rome by the first century. Pliny misunderstood silk production: he thought silk was made from a “white down that adheres to … leaves,” which the people of Seres combed off and made into thread. (His description more accurately describes cotton.) Yet in another passage he wrote about silkworms.

37

Modern interpreters often translate Seres as China, but, to the Romans, it was actually an unknown land on the northern edge of the world.

China was not the only manufacturer of silk in Pliny’s day. As early as 2500

BCE

, the ancient Indians wove silk from the wild silk moth, a different species of silkworm than the one the Chinese had domesticated. In contrast, the Indians collected broken cocoons that remained after the silk worms had matured into moths, broken through their cocoons, and flown away.

38

Similarly, in antiquity, the Greek island of Cos in the eastern Aegean produced Coan silk, which was also spun from the broken cocoons of wild silk moths. Early on, the Chinese had learned to boil the cocoons, which killed the silk worms, leaving the cocoons intact and allowing the thread to be removed in long, continuous strands. Even so, Chinese silk cannot always be distinguished from wild silk, and it is possible that Pliny may have described Indian or Coan, not Chinese, silk.

39

Because Chinese and Coan silk resemble each other so closely, analysts must identify motifs unique to China in order to determine the origins of a piece of silk. Yet since any motif can be copied, the most reliable indicator of Chinese manufacture is the presence of Chinese characters, which only the Chinese wove into their cloth. Textiles found in Palmyra, Syria, from the first to third centuries

CE

were among the earliest Chinese silks to reach west Asia from China.

40

The Chinese emperor routinely sent envoys to the Western Regions to bestow textiles on local rulers, and they in turn probably sent them further west.

Still, most of the beautiful silks found in Europe that are labeled “Chinese” were actually woven in the Byzantine Empire (476–1453

CE

). One scholar who examined a thousand examples dating between the seventh and thirteenth century found only one made in China.

41

Silk in particular drew Pliny’s ire because he simply could not understand why the Romans imported fabric that left so much of the female body exposed: “So manifold is the labor employed, and so distant is the region of the globe drawn upon, to enable the Roman matron to flaunt transparent raiment in public.”

42

He railed against other imported goods as well—frankincense, amber, and tortoiseshell, among others—because consuming them, in his opinion, weakened Rome.

43

Had the trade between China and Rome been as significant as Pliny contended, some Roman coins would presumably have been found in China. Yet the earliest European coins unearthed in China are from Byzantium, not Rome, and date to the 530s and 540s.

44

Vague rumors to the contrary, not a single Roman coin has turned up in China—in contrast to the thousands of Roman gold and silver coins excavated on the south Indian coast, where Roman traders often journeyed.

45

Historians sometimes argue that coins made from precious metals could have circulated between two places in a given period but might not survive today because they were melted down. But the survival of so many later non-Chinese coins in China undercuts this argument. Many Iranian coins made of silver and minted by the Sasanian Empire (224–651) have appeared in quantities as large as several hundred (see the example in plate 4B).

In sum, the absence of archeological or textual evidence suggests surprisingly little contact between ancient Rome and the Han dynasty. Although Pliny the Elder offered a confident critique of the silk trade, no one in the first century

CE

collected any reliable statistics about Rome’s balance of trade.

46

If Romans had bought Chinese silk with Roman coins, some remnants of Chinese silk might have surfaced in Rome. Starting in the second and third centuries, a few goods managed to make their way between Rome and China. This is the period of the Palmyra silks and also when Romans began to pin down the location of Seres.

The art-historical record in China also confirms intermittent contacts between Rome and China that accelerate in the second and third centuries

CE

. In the Han dynasty, only a few rare examples of Chinese art display foreign motifs. But by the Tang dynasty much more Chinese art incorporated Persian, Indian, and even Greco-Roman motifs.

47

The Tang dynasty marked the high point of Chinese influence in Central Asia and also the height of the Silk Road trade.

This book starts with the first perceptible contacts between China and the West in the second and third centuries

CE

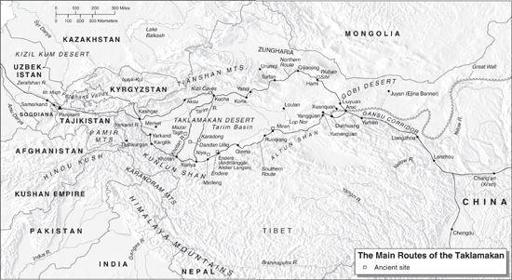

and concludes in the early eleventh century, the time of the latest excavated documents from Dunhuang and Khotan. Proceeding in chronological order, each chapter examines a different Silk Road site, chosen for its documentary finds. Niya, Kucha, Turfan, Dunhuang, and Khotan are in northwest China. Samarkand lies in Uzbekistan, while the nearby site of Mount Mugh is located just across the border in modern Tajikistan. The seventh, Chang’an, the capital of the Tang dynasty, is in Shaanxi Province in central China.

Chapter 1 begins with the sites of Niya and Loulan, because they have produced extensive documentary evidence of the first sustained cultural contacts among the local peoples, the Chinese, and a group of migrants from the Gandhara region of modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan. These migrants introduced their own script and imported a technology for keeping written records on wood; they were also among the first Buddhists to enter the Western Regions. Even though Buddhist regulations, or

vinaya,

prescribed celibacy for monks and nuns, many of these Buddhists at Niya married, had children, and lived with their families, not in celibate monastic communities, as is so often thought.

Kucha, the subject of

chapter 2

, was home to one of China’s most famous Buddhist translators, Kumarajiva (344–413), who produced the first understandable versions of Buddhist texts in Chinese. Kumarajiva grew up speaking the local Kuchean language, studied Sanskrit as a young boy, and learned Chinese after being held captive in China for seventeen years. The Kuchean documents have excited a century of passionate debate among linguists trying to solve the puzzle of why a people living in the Western Regions spoke an Indo-European language so different from the other languages of the region.

The Sogdians were the most important foreign community in China at the peak of the Silk Road exchanges. Many Sogdians settled permanently in Turfan on the northern route, the site discussed in

chapter 3

, where they pursued different occupations, including farming, running hostels, veterinary medicine, and trading.

48

In 640, when Tang-dynasty armies conquered Turfan, all the residents came under direct Chinese rule. Turfan’s extremely dry conditions have preserved an unusual wealth of documents about daily life in a Silk Road community.

Chapter 4 focuses on the Sogdian homeland around Samarkand in modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. While China has gained a reputation as a country that does not welcome outsiders, large communities of foreigners moved to China in the first millennium, particularly after Samarkand fell to Muslim forces in 712.

Some of the most exciting archeological finds in recent years have been the tombs of foreigners resident in the Tang-dynasty capital at Chang’an, or modern Xi’an, discussed in

chapter 5

. The Sogdian migrants from the Iranian world brought their Zoroastrian beliefs with them; they worshipped at fire altars and sacrificed animals to the gods. After they died, their kin prepared them for the next world by leaving the corpses exposed to predators who cleaned the bones of flesh—thought to pollute the earth—before burial. Although most Sogdians subscribed to Zoroastrian teachings, several Sogdians living in Chang’an at the end of the sixth and in the early seventh century opted for Chinese-style burials instead. These tombs portray the Zoroastrian afterlife in far more detail than any art surviving in the Iranian world.

Some 40,000 documents from the library cave at Dunhuang, covered in

chapter 6

, form one of the world’s most astounding collections of treasures, which includes the world’s earliest printed book, The Diamond Sutra. A monastic repository, the library cave contained much more than Buddhist materials, because so many other types of texts were copied on the backs of Buddhist texts. The cave paintings at Dunhuang are certainly the best preserved and most extensive of any Buddhist site in China; they testify to the devotion of the local people as well as the rulers who commissioned such beautiful works of art. Even as they created these masterpieces, Dunhuang residents did not use coins but instead paid for everything using grain or cloth, as was true of all the Western Regions after the withdrawal of Chinese troops in the mid-eighth century.

The rulers of Dunhuang maintained close ties to the oasis of Khotan, the focus of

chapter 7

, which lies on the southern Silk Road just west of Niya. Almost all surviving documents are written in Khotanese, an Iranian language with a huge vocabulary of words borrowed from Sanskrit; they were found at the library cave in Dunhuang and in towns surrounding Khotan. Oddly, none of these early documents have surfaced in the oasis of Khotan itself. These documents include language-learning aids showing how Khotanese students learned Sanskrit, the language used in most monasteries, and Chinese, a language spoken widely in the Western Regions. Conquered in 1006, Khotan was the first city in today’s Xinjiang to convert to Islam, and, as visitors today observe, Xinjiang is still heavily Muslim. The chapter concludes by surveying the history and trade of the region since the coming of Islam.

In sum, this book’s goal is to sketch the main events in the history of each oasis community, describe the different groups who resided there and their cultural interactions, outline the nature of the trade, and ultimately tell the flesh-and-blood story of the Silk Road, a story most commonly written on recycled paper.

CHAPTER 1

At the Crossroads of Central Asia

The Kingdom of Kroraina

I

n late January 1901, even before Aurel Stein arrived at the site of Niya, his camel driver gave him two pieces of wood with writing on them. Stein, to his “joyful surprise,” recognized the Kharoshthi script, which was used to write Sanskrit and related vernacular Indian languages in the third and fourth centuries

CE.

1

One of these two documents appears on this page—part of a historic cache proving that the Silk Road played a paramount role in transmitting languages, culture, and religion, which is why this book begins with a chapter about the ancient lost city of Niya.