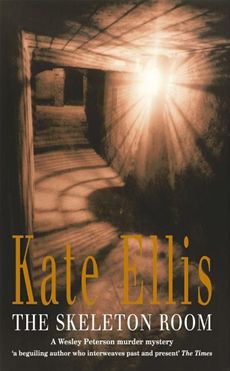

The Skeleton Room

The Merchant’s House

The Armada Boy

An Unhallowed Grave

The Funeral Boat

The Bone Garden

A Painted Doom

For more information regarding Kate Ellis log on to Kate’s

website:

www.kateellis.co.uk

Published by Hachette Digital

ISBN: 978-0-74812-668-2

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2003 by Kate Ellis

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Hachette Digital

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London, EC4Y 0DY

With many thanks to Judy Lees for all her help.

20 July

The woman in the red T-shirt lay on the sharp grey rocks far below; distant and tiny, like a small fish caught in the teeth

of some gigantic sea creature.

The figure on the cliff top above stared down and swayed slightly to the rhythm of the waves. The sea would soon swallow the

woman in the red T-shirt and carry her off. Over the centuries the sea had claimed many lives around this coast. So what was

one more?

Seagulls shrieked overhead like souls in torment while fat bees buzzed, busy in the greenery. For a moment the watcher stood

listening to the sounds of nature, then took a step forward, careful not to go too near the edge. There was no movement down

below on the rocks; the woman in the red T-shirt lay there twisted, her lifeless limbs spread out against the grey stone in

a clumsy parody of sunbathing.

The watcher felt in a pocket to check that the letter was safe before glancing at an expensive watch. It was time to go now,

to get away before others came along to enjoy the awesome beauty of the cliff top.

It had been easy this time. In fact murder became easier with each passing year.

My sorry tale begins in the year of Our Lord 1771 when I was newly appointed to the parish of Millicombe. At the hour of ten

o’clock one Friday in April of that year, I was called to the hamlet of Chadleigh to visit a certain farmhand called George

Marbis, who, by all accounts, was close to death. His daughter, Margaret, had run along the coast path to Millicombe at that

late hour and my maidservant showed her into the study where I was composing my sermon for the following Sunday. The girl,

Margaret, a poor, thin creature, pleaded with me to come with her, saying that her father was most troubled and had asked

to see me. As vicar, I felt obliged to give the dying man some words of comfort, so I went with Margaret to Marbis’s cottage,

which I found to be a dark, foul-smelling place, hardly fit for the animals he tends.Marbis was indeed close to meeting his Maker, and I prepared to utter the words of comfort I use at such unhappy times.

But Marbis would have none of my prayers. He clawed at my sleeve with his bony hands and said that he wished to speak with

me in private. Margaret, who had cared for her father since her mother’s untimely death in childbed, busied herself about

the cottage, and the dying man bade me stoop so he could whisper in my ear. His breath was

noxious but I obliged him. Yet afterwards I wished I had refused, because what he had to tell me was a secret so vile that

it were best not to hear it.From

An Account of the Dreadful and Wicked Crimes of the Wreckers of Chadleigh

by the Reverend Octavius Mount, Vicar of Millicombe

23 July

Ian Jones watched his colleague wield the sledgehammer, fearful that one misplaced blow would bring the huge edifice of Chadleigh

Hall crashing to the ground.

‘You sure that’s not a supporting wall, Marty?’

‘’Course I’m bloody sure.’

Marty Shawcross raised the hammer while Ian scratched his shaved head. At least they’d have plenty of time to get out if the

ceiling started to collapse.

A few foundation-shaking thuds later, when the dense cloud of plaster dust had begun to settle, Marty and Ian looked at the

small jagged hole that they had made in the wall.

‘You were right. Looks like a doorway. It’s been blocked off.’

‘What did I tell you?’ Marty reached out and pushed the loose plaster from the edge of the hole. ‘Do we carry on or what?’

‘Ours not to reason why – ours just to do what’s on the plans. Give it another bash.’

Marty obeyed and dust and debris flew into the air as the hole expanded. The men coughed and Ian took a grubby handkerchief

from his pocket and held it to his face.

‘We’re meant to be knocking through to the next room but this looks like some sort of cupboard or . . . I’m having a look.’

‘Go on, then. Rather you than me.’

Marty watched as Ian poked his head through the hole and quickly pulled it out again.

‘Can’t see a bloody thing. Got your lighter?’

Marty, a incorrigible smoker, pulled a cheap disposable cigarette lighter from his trouser pocket and handed it to Ian, who

lit it and held it just inside the gaping hole.

After a few seconds of silence, Ian turned to face his companion. The blood had drained from his face, leaving it as white

as the plaster dust that was settling on the splintery floorboards.

‘What is it? What did you see?’

It was a while before Ian felt up to answering.

Neil Watson had dived down to the wreck of the

Celestina

several times. But, being a creature of habit, he preferred to work on dry land, dealing with the artefacts the divers were

bringing up from the seabed, viewing their video footage and writing reports in the disused beach café that they were using

as their site headquarters.

He was unused to working in such splendid isolation. He missed the hustle and bustle of a land-based dig and the chatter of

his colleagues, most of whom were working aboard the boat or diving beneath the sea.

But today he had company. A couple of bored-looking youths – Oliver Kilburn and his friend, Jason Wilde, aged eighteen and

both at a loose end since the finish of their final school exams – had volunteered to help with the finds from the wreck.

And as Oliver’s father was Dominic Kilburn, the businessman who owned the beach, Neil felt he could hardly complain that the

pair were unreliable and turned up only when it suited them.

Satisfied that the boys weren’t doing too much damage to the delicate objects brought up from the seabed, Neil stepped outside

the café onto the sandy concrete steps that led down to the beach. He shaded his eyes against the sun and squinted at the

dive boat, which bobbed near the rocks, watching the figures on the deck, divers in shiny black with brightly coloured air

tanks on their backs.

Neil knew that their main enemy was the weather. The

ship’s timbers had been uncovered by a freak storm three weeks before and discovered by amateur divers, who had reported

their find to the relevant authorities. And, if nature decided not to cooperate, another storm could cover the remains of

the

Celestina

up again just as quickly. They were working against the clock, and Neil Watson preferred to work at his own pace.

‘How’s it going, then, Dr Watson?’

Neil swung round. A tall man was standing on top of a rock to his left, outlined against the sun. Neil shielded his eyes,

feeling small and subservient as he gazed up at the towering figure. But perhaps this was Dominic Kilburn’s intention.

‘We’re making good progress. They’ve uncovered more of the timbers and found a lot of interesting stuff. Your son’s in there

washing the pottery they brought up this morning – high-status stuff, probably from the captain’s cabin. Want to take a look?’

Neil pointed at the shabby wooden building near by which had been a beach café and ice-cream shop in the days when the cove

had been the property of a neighbouring girls’ boarding school which had allowed its use by the public.

But Dominic Kilburn’s mind was on more important things than old pottery. ‘Is there any sign of . . .?’

‘No. Nothing like that.’

‘Can you use metal detectors down there? Speed things up a bit?’

‘I can assure you that we are carrying out a thorough investigation of the site. We’ll use metal detectors if they’re considered

appropriate,’ said Neil with academic dignity, as though Dominic Kilburn had made an obscene suggestion.

Kilburn jumped down off his rock, walked up to Neil and put his face close to his. ‘I’m footing the bill for this, so if I

say get a move on, you get a move on.’

Neil pretended not to notice the threat in Kilburn’s voice.

‘You can’t just strip the wreck of anything that might be worth a few bob, you know. Everything has to be recorded, photographed

and drawn

in situ

, and any finds need to be conserved properly. We don’t cut corners. We’re archaeologists, not treasure hunters.’

‘So what about all these stories? Surely you’ve found some signs of . . .’

‘Don’t get your hopes up. There’s a chance we won’t find anything like that.’

Kilburn was about to reply when his son appeared at the café door. Oliver Kilburn was tall, classically good looking with

fine fair hair. Neil noticed a distinct family resemblance and wondered, not for the first time, whether the boss’s son was

a helper or a spy in their midst. Kilburn greeted Oliver with a scowl, seemingly annoyed by the interruption, but before he

could say anything the sound of raised voices drifted over on the breeze, clear above the cry of the seagulls and the thunder

of the waves. Something was happening.

Neil shaded his eyes and looked out to sea. A dinghy was approaching, its outboard motor thrusting it through the waves at

full speed. Without a word he left the Kilburns, father and son, and ran towards the waterline to meet it. When the dinghy

reached the shore Matt jumped out, anxious to relay some news. Neil glanced back and saw that Dominic Kilburn was standing

beside his son, watching expectantly, no doubt hoping that Matt was bringing the news he had been waiting for since he had

first heard the story of the

Celestina

.

But what Matt had to say didn’t concern sunken treasure. After a brief conversation, Neil took his mobile phone from his pocket

and looked at it despairingly. There was no signal. He swore under his breath and looked up to find Dominic Kilburn and his

son standing beside him.

‘What’s going on? What have they found?’

Neil didn’t answer. ‘I need to get to a phone. There’s no mobile signal around here.’

‘There’s a cottage up on the cliff top. You pass it on the way down to the beach,’ said Oliver Kilburn in an attempt to be

helpful.

‘Thanks,’ Neil mumbled. At least the boy’s suggestion had been a good one.

He looked out to sea again, ignoring Dominic Kilburn’s repeated questions. He could see that the diving team were dragging

something onto their boat but he didn’t hang around. He rushed off up the sand, leaving a neat trail of footprints behind

him, and scaled the steep and overgrown path to the lane above.

When he reached the top he paused to catch his breath, but then he ran on. Fifty yards down the lane he found a small, brick-built

cottage fronted by a long and overgrown garden. The gate bore the name ‘Old Coastguard Cottage’ on a rustic wooden plaque,

but Neil had no time to take in the architectural niceties: he rushed up the garden path, ignoring the tall, toppled flowers

that ambushed his legs, and banged on the front door. The sound was urgent – but then it was meant to be.

A thin, dark-haired man in his early thirties opened the door a fraction and peeped round suspiciously, as though he feared

a raid of some kind. When Neil explained the reason for his visit the door opened a little wider, and after a few seconds

he was allowed into the hallway.

The man pointed to an old-fashioned telephone, which stood on the hall table, and he watched in silence as Neil dialled the

numbers: 999.

‘Police,’ Neil said calmly, instinctively turning away from the man. ‘We’ve found a body in the sea at Chadleigh Cove.’

When Neil turned round he saw that the colour had drained out of his host’s face.

The two policemen climbed out of the car and admired the view. Chadleigh Hall had been built at a time when pleasing proportions

were all the rage.

‘It’ll be nice when it’s finished,’ commented the elder of

the pair, a big man with unruly hair, an expanding midriff and a prominent Liverpool accent.

‘What are they doing to it?’

‘Turning it into one of them posh country hotels. Nothing that need concern us on our salaries.’

The younger man smiled. ‘I suppose we’d better see what all the fuss is about.’

As if on cue, a uniformed constable appeared, shaded by the magnificent Georgian portico. He raised his hand in greeting.

‘Sorry to drag you out, sir,’ he said, addressing the older man and ignoring his companion. ‘But a couple of workmen have

turned up a body. They were knocking a wall through and they found a skeleton. I reckon it looks suspicious,’ he added seriously.

‘Right, then, George, lead us to it.’

The constable led the way through what was once, and no doubt would be again, a magnificent entrance hall, now filled with

scaffolding, large paint pots and the tools of the builder’s trade. They ascended a sweeping, dust-covered staircase and passed

through a series of rooms, each stripped bare to the plaster and awaiting the attentions of electricians and decorators.

The younger CID officer breathed in, the smell of fresh paint reminding him that he had promised his wife that he would decorate

the bedroom some time soon – work permitting.

Stepping through another doorway, they found themselves in a smaller room, as bare as the rest. Two men were sitting on wooden

stools: the smaller of the pair was a monkey-like man with the wizened skin of a heavy smoker, the larger sported a fine beer

belly and had more hair on his body than on his head. They stared at the newcomers.

‘This is Detective Chief Inspector Heffernan and er . . .’ The constable hesitated. He knew Gerry Heffernan – everybody knew

Gerry Heffernan – but he hadn’t come across his colleague before, although he’d heard of his existence:

there weren’t that many black detective inspectors in the local force.

‘Detective Inspector Peterson,’ the younger man said quietly.

‘They’ve come to ask you a few questions,’ the constable said with relish.

‘Right, then, let’s get on with it, shall we,’ Heffernan began, looking from one to the other. ‘Which of you found this skeleton?’

‘We both did, I suppose. But Ian went inside to have a look and I stayed out here. It gave me the creeps just looking at it.’

Marty Shawcross shuddered.

‘Can you tell us what happened?’

Marty looked at the policeman who spoke. Detective Inspector Peterson possessed a quiet air of authority which Marty assumed

was bestowed by his police warrant card.

‘We didn’t know it was there,’ Marty said defensively. There was no way they were going to lay any blame on him. ‘The plans

said this wall was to be knocked through so me and Ian started and there was this sort of room and . . .’

‘It must have given you a shock.’ Wesley Peterson did his best to look sympathetic.

‘Nearly gave me a bleeding heart attack seeing that thing staring at me.’

‘Me and all,’ Ian chipped in, not wanting to be left out.

Heffernan plunged his hands into his trouser pockets and looked Marty in the eye. ‘Well, if you’ve recovered perhaps you could

give a statement to the constable here while me and Inspector Peterson have a look at what you’ve found.’

Marty nodded. ‘We thought we were just knocking through to the room next door. We reckoned it was a cupboard or something.

It’s nothing to do with us really. We just . . .’

Wesley Peterson decided to interrupt the protestations of

innocence. ‘Do you know anything about this place? Who were the previous owners?’