The Sleepwalkers (169 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

What

he

did

was

to

found

the

modern

science

of

dynamics,

which

makes

him

rank

among

the

men

who

shaped

human

destiny.

It

provided

the

indispensable

complement

to

Kepler's

laws

for

Newton's

universe:

"If

I

have

been

able

to

see

farther,"

Newton

said,

"it

was

because

I

stood

on

the

shoulders

of

giants."

The

giants

were,

chiefly,

Kepler,

Galileo

and

Descartes.

2.

Youth of Galileo

Galileo

Galilei

was

born

in

1564

and

died

in

1642,

the

year

Newton

was

born.

His

father,

Vincento

Galilei,

was

an

impoverished

scion

of

the

lower

nobility,

a

man

of

remarkable

culture,

with

considerable

achievements

as

a

composer

and

writer

on

music,

a

contempt

for

authority,

and

radical

leanings.

He

wrote,

for

instance

(in

a

study

on

counter-point):

"It

appears

to

me

that

those

who

try

to

prove

an

assertion

by

relying

simply

on

the

weight

of

authority

act

very

absurdly."

1

One

feels

at

once

the

contrast

in

climate

between

the

childhoods

of

Galileo

and

our

previous

heroes.

Copernicus,

Tycho,

Kepler,

never

completely

severed

the

navel-cord

which

had

fed

into

them

the

rich,

mystic

sap

of

the

Middle

Ages.

Galileo

is

a

second-generation

intellectual,

a

second-generation

rebel

against

authority;

in

a

nineteenth

century

setting,

he

would

have

been

the

Socialist

son

of

a

Liberal

father.

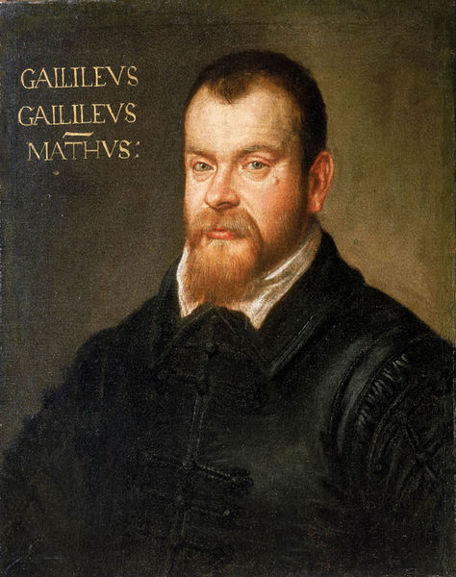

His

early

portraits

show

a

ginger-haired,

short-necked,

beefy

young

man

of

rather

coarse

features,

a

thick

nose

and

conceited

stare.

He

went

to

the

excellent

Jesuit

school

at

the

Monastery

of

Vallombrosa,

near

Florence;

but

Galileo

senior

wanted

him

to

become

a

merchant

(which

was

by

no

means

considered

degrading

for

a

patrician

in

Tuscany)

and

brought

the

boy

home

to

Pisa;

then,

in

recognition

of

his

obvious

gifts,

changed

his

mind

and

at

seventeen

sent

him

to

the

local

university

to

study

medicine.

But

Vincento

had

five

children

to

look

after

(a

younger

son,

Michelangelo,

plus

three

daughters),

and

the

University

fees

were

high;

so

he

tried

to

obtain

a

scholarship

for

Galileo.

Although

there

were

no

less

than

forty

scholarships

for

poor

students

available

in

Pisa,

Galileo

failed

to

obtain

one,

and

was

compelled

to

leave

the

University

without

a

degree.

This

is

the

more

surprising

as

he

had

already

given

unmistakable

proof

of

his

brilliance:

in

1582,

in

his

second

year

at

the

University,

he

discovered

the

fact

that

a

pendulum

of

a

given

length

swings

at

a

constant

frequency,

regardless

of

amplitude.

2

His

invention

of

the

"pulsilogium",

a

kind

of

metronome

for

timing

the

pulse

of

patients,

was

probably

made

at

the

same

time.

In

view

of

this

and

other

proofs

of

the

young

student's

mechanical

genius,

his

early

biographers

explained

the

refusal

of

a

scholarship

by

the

animosity

which

his

unorthodox

anti-Aristotelian

views

raised.

In

fact,

however,

Galileo's

early

views

on

physics

contain

nothing

of

a

revolutionary

nature.

3

It

is

more

likely

that

the

refusal

of

the

scholarship

was

due

not

to

the

unpopularity

of

Galileo's

views,

but

of

his

person

–

that

cold,

sarcastic

presumption,

by

which

he

managed

to

spoil

his

case

throughout

his

life.

Back

home

he

continued

his

studies,

mostly

in

applied

mechanics,

which

attracted

him

more

and

more,

perfecting

his

dexterity

in

making

mechanical

instruments

and

gadgets.

He

invented

a

hydrostatic

balance,

wrote

a

treatise

on

it

which

he

circulated

in

manuscript,

and

began

to

attract

the

attention

of

scholars.

Among

these

was

the

Marchese

Guidobaldo

del

Monte

who

recommended

Galileo

to

his

brother-in-law,

Cardinal

del

Monte,

who

in

turn

recommended

him

to

Ferdinand

de

Medici,

the

ruling

Duke

of

Tuscany;

as

a

result,

Galileo

was

appointed

a

lecturer

in

mathematics

at

the

University

of

Pisa,

four

years

after

that

same

University

had

refused

him

a

scholarship.

Thus

at

the

age

of

twenty-five,

he

was

launched

on

his

academic

career.

Three

years

later,

in

1592,

he

was

appointed

to

the

vacant

Chair

of

Mathematics

at

the

famous

University

of

Padua,

again

through

the

intervention

of

his

patron,

del

Monte.