The Small House Book (5 page)

Read The Small House Book Online

Authors: Jay Shafer

A Sausalito houseboat

37

Too Good To Be Legal

It is illegal to inhabit a tiny home in most popu-

lated areas of the U.S. The housing industry and

the banks sustaining it spent much of the 1970s

and 1980s pushing for larger houses to produce

more profit per structure, and housing authori-

ties all cross the country adopted this bias in

the form of minimum-size standards. The stated

purpose of these codes is to preserve the high

quality of living enjoyed in our urban and sub-

urban areas by defining how small a house can

be. They govern the size of every habitable room and details therein. By aim-

ing to eliminate all but the most extravagant housing, size standards have

effectively eliminated housing for everyone but the most affluent Americans.

No Problem Too Small

Again, the intention of these limits is to keep unsightly little houses from pop-

ping up and lowering property values in America’s communities and, more-

over, to ensure that the housing industry is adequately sustained. The actual

results of the limits are a greater number of unsightly large houses, inordi-

nate construction waste, higher emissions, sprawl and deforestation, and, for

those who cannot afford these larger houses, homelessness.

One of the leading causes of homelessness in this country is, in fact, our

shortage of low-income housing. After mental illness and substance abuse,

minimum-size standards have probably kept more people on the street than

any other contributing factor. Countless attempts to design and build efficient

38

Another Sausalito Houseboat (above)

forms of shelter by and for the homeless have been thwarted by these codes.

By demanding all or nothing from our homes, current restrictions ensure that

the have-nots have nothing at all. The U.N. Declaration of Universal Human

Rights (of which the United States is a signatory) holds shelter to be a fun-

damental human right. Yet, in the U.S.. this right is guaranteed only to those

with enough money to afford the opulence.

The stated premise of these well-intentioned codes is as profoundly flawed as

their results. Little houses have not been shown to lower the values of neigh-

boring large residences. In fact, the opposite holds true. When standard-

sized housing of standard materials and design goes up next to smaller, less

expensive dwellings, for which some of the budget saved on square footage

has been invested in quality materials and design, the value of the smaller

places invariably plummets while that of the derelict mansions is raised.

Protecting “the health, safety and welfare not only of those persons utilizing a

house but the general public as well” is the stated purpose of minimum-size

standards. But, by prohibiting the construction of small homes, these codes

clearly circumvent their own alleged goal. It would seem far more effective

to outlaw the kind of toxic real estate that such codes currently mandate. An

even more reasonable and less draconian system would allow individuals to

determine the size of their own homes- large or small.

Some of us prefer to devote our time to our children, artistic endeavors, spiri-

tual pursuits or relaxing. Others would rather spend their time generating

disposable income. Some enjoy living simply, while others like taking risks.

Every American should be free to choose a simple or an extravagant lifestyle

and a house, to accommodate it.

39

Mi Casa Es Su Asset

In his book,

How Buildings Learn

, Stuart Brand speaks of the difference be-

tween “use value” and “market value”:

Economists dating back to Aristotle make a distinction between “use value”

and “market value.” If you maximize use value, your home will steadily be-

come more idiosyncratic and highly adapted over the years. Maximizing

market value means becoming episodically more standard, stylish, and in-

spectable in order to meet the imagined desires of a potential buyer. Seek-

ing to be anybody’s house it becomes nobody’s. 5

On the surface, small dwellings may seem to afford greater utility than mar-

ketability. These places are typically produced by people who are more con-

cerned about how well a house performs as a home than how much it could

sell for. The creation of a smart little house has traditionally been a labor of

love because, until recently, love of home has been its only apparent re-

ward. As a rule, Americans like to buy big things. Like fast food, the standard

American house offers more frills for less money. This is achieved primarily

by reducing quality for quantity’s sake.

Financiers have been banking on this knowledge for decades. From their

perspective, a sound investment is one that corresponds with the dominant

market trend. Oversized houses are more readily financed because they are

what most Americans are looking for. For a lender, two bedrooms are better

than one, because, whether the second room gets used or not, this is what

the market calls for. Sometimes a bank will simply refuse to finance a small

home because the cost per square foot is too high or the land upon which the

house sits is too expensive in proportion to the structure. The design, con-

struction or purchase of a small house has thus been further discouraged.

40

Despite all obstacles, a few relentless claustrophiles do continue to fight for

their right to the tiny, and it has finally begun to pay off. Lawsuits concerning

the constitutionality of minimum-size standards have recently forced some

municipalities to drop the restrictions. Where this is the case, little dwell-

ings have begun to pop up, and they are selling fast. Americans looking for

smaller, well-built houses are out there, and their needs have been refused

for decades. This minority, comprised mostly of singles, may be small, but it

is ready to buy. It seems the composition of American households changed

some time ago, and the dwellings that house them are just now being al-

lowed to catch up.

Some developers on the West Coast have been quick to take advantage of

the fresh market potential. In one high-income neighborhood, new houses of

just 400 square feet are selling for over $120,000, and some at 800 square

feet are going for more than $300,000. That is about 10 percent more per

square foot than the cost of 2,000 square-foot houses in the immediate area.

Needless to say, post-occupancy reports show that, though less expensive

overall, these little homes have not had a negative impact on neighboring

property values. In fact, the resale value of American houses of 2,500 square

feet or more appreciated 57 percent between 1980 and 2000, while houses

of 1,200 or less appreciated 78 percent (Elizabeth Rhodes,

Seattle Times

,

2001). Small houses appreciated $37 more per square foot.

41

Meeting Code

I should be clear that, despite the absurdities in their codebooks, our local

housing officials are not necessarily absurd people. This is important to re-

member if you are about to seek their approval for a project. Building codes

are made at the national level, but they are adopted, tailored and enforced at

the local level. View your housing department as the helpful resource it wants

to be, not as an adversary. Once your local officials are politely informed

about the actual consequences of the codes they have been touting, the

codes are likely to change. Be sure to provide plenty of evidence about the

merits of smaller houses, including documentation of projects similar to the

one you intend to build. Codes are generally amended annually by means

of a review and hearing process anyone in the community can take part in.

Diplomacy is one way of clearing the way for a small house. Moving is an-

other. Some remote areas of the country have no building codes at all, and

a few others have a special “owner-builder” zoning category that exempts

people who want to build their own homes from all but minimal government

oversight. Provisions for alternative construction projects also exist. Section

104.11 of the International Building Code encourages local departments to-

weigh the benefits of alternative design, materials and methods in the course

of evaluating a project. Several counties permit accessory dwellings. These

small outbuildings are also known as “granny flats” because they can be in-

habited by a guest, teenager, or elderly member of the family.

Terminology can sometimes provide wiggle-room within the laws. “Temporary

housing” is, for example, a term often used by codebooks to describe “any

tent, trailer, motor home or other structure used for human shelter and de-

signed to be transportable and not attached to the ground, to another struc-

42

ture or to any utility system on the same premises for more than 30 calendar

days.” Such structures are usually exempt from building codes. So, as long

as a small home is built to be portable, with its own solar panel, composting

toilet, and rain water collection system (or just unplugged once a month), it

can sometimes be inhabited on the lot of an existing residence indefinitely.

Most municipalities are eager to endorse a socially-responsible project, but

occasionally, a less savvy housing department will dig in its heels. When

relocating to an area where smaller homes are legal is not an option, there

may still be recourse. Political pressure can be applied on departments to

great effect. While an official may have no trouble telling one individual that

his plans for an affordable, high-quality, ecologically-sound home will not fly,

the same official may have a great deal more trouble letting his objections

be known publicly through the media. Newspeople love a good David-and-

Goliath story as much as their audiences do.

As mentioned earlier, minimum-size standards have been found to be uncon-

stitutional in several U.S. courts. If all else fails, a lawsuit against the local

municipality remains a final option. This strategy, and any involving politi-

cal pressure through the media, should be reserved only for circumstances

where all other avenues have been explored and exhausted. Remember that

ridiculous codes do not usually reflect the mind-set of those who have been

asked to enforce them. Take it easy on your local officials and they will more

than likely make things easy for you.

43

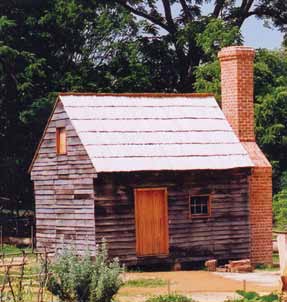

Guerilla Housing

We are in the midst of a housing

crisis. The Bureau of the Census

has determined that more than for-

ty percent of this country’s families

cannot afford to buy a house in the

U.S. Over 1,500 square miles of ru-

ral land are lost to compulsory new

housing each year. An immense

portion of this will be used for noth-

ing more than misguided exhibi-

tionism. We clearly need to change

our codes and financing structure

and, most importantly, our current

attitudes about house size.

Minimum-size standards are slowly eroding as common sense gradually

makes its way back onto the housing scene. Where negotiation and political