The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (23 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

IMPRISONMENT AND INEQUALITY

We used statistics on the proportion of the population imprisoned in different countries from the United Nations

Survey on Crime Trends and the Operations of Criminal Justice Systems

.

212

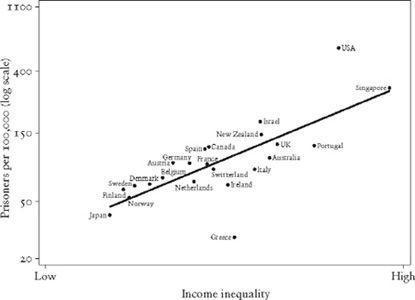

Figure 11.1 shows (on a log scale) that more unequal countries have higher rates of imprisonment than more equal countries.

In the USA there are 576 people in prison per 100,000, which is more than four and a half times higher than the UK, at 124 per 100,000, and more than fourteen times higher than Japan, which has the lowest rate at 40 per 100,000. Even if the USA Singapore are excluded as outliers, the relationship is robust among the remaining countries. and

Figure 11.1

More people are imprisoned in more unequal countries.

149

Figure 11.2

More people are imprisoned in more unequal US states.

149

For the fifty states of the USA, figures for imprisonment in 1997–8 come from the US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

243

As Figure 11.2 shows, there is again a strong relationship between imprisonment and inequality, and big differences between states – Louisiana imprisons people at more than six times the rate of Minnesota.

The other thing to notice on this graph is that states are shown using two different symbols. The circles represent states that have abolished the death penalty; diamonds are states which have retained it.

As we pointed out in Chapter 2, these relationships with inequality occur for problems which have steep social gradients within societies. There is a strong social gradient in imprisonment, with people of lower class, income and education much more likely to be sent to prison than people higher up the social scale. The rarity of middle-class people being imprisoned is highlighted by the fact that two sociologists at California State Polytechnic thought it worthwhile to publish a research paper describing a middle-class inmate’s adaptation to prison life.

244

Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of imprisonment are one way of showing the inequalities in risk of being imprisoned. In America, the racial gap can be measured as the ratio between imprisonment rates for whites and blacks.

245

Hawaii is the only state where the risk of being imprisoned doesn’t seem to differ much by race. There, the risk of being imprisoned if you are black is 1.34 times as high as if you are white. In every other state of the union ratios are greater than 2. The ratio is 6.04 for the USA as a whole and rises to 13.15 for New Jersey. There is a similar picture in the UK, where members of ethnic minorities are much more likely to end up in prison.

246

Are these ethnic inequalities a result of ethnic disparities in rates of crimes committed? Research on young Americans suggests not.

247

Twenty-five per cent of white youths in America have committed one violent offence by age 17, compared to 36 per cent of African-Americans, ethnic rates of property crime are the same, and African-American youth commit fewer drug crimes. But African-American youth are overwhelmingly more likely to be arrested, to be detained, to be charged, to be charged as if an adult and to be imprisoned. The same pattern is true for African-American and Hispanic adults, who are treated more harshly than whites at every stage of judicial proceedings.

248

Facing the same charges, white defendants are far more likely to have the charges against them reduced, or to be offered ‘diversion’ – a deferment or suspension of prosecution if the offender agrees to certain conditions, such as completing a drug rehabilitation programme.

DEGREES OF CIVILIZATION

Prison data show us that more unequal societies are more punitive. There are other indicators of this in the ways that offenders are treated in different penal systems. First, as Figure 11.2 shows, more unequal US states are more likely to retain the death penalty. Second, how prisoners are treated seems to differ.

Discussing the Netherlands, David Downes describes how a group of criminal lawyers, criminologists and psychiatrists came together to influence the prison system. They believed that:

the offender must be treated as a thinking and feeling fellow human being, capable of responding to insights offered in the course of a dialogue . . . with therapeutic agents.

241

, p. 147

This philosophy has, he says, resulted in a prison system that emphasizes treatment and rehabilitation. It allows home leave and interruptions to sentences, as well as extensive use of parole and pardons. Prisoners are housed in single cells, relations among prisoners and between prisoners and staff are good, and programmes for education, training and recreation are considered a model of best practice. Although the system has toughened up somewhat since the 1980s in response to rising crime (mostly a consequence of rising rates of drug trafficking and the use of the Netherlands as a base for international organized crime), it remains characteristically humane and decent.

Japan is another country with a very low rate of imprisonment. Prison environments there have been described as ‘havens of tranquillity’.

249

The Japanese judicial system exercises remarkable flexibility in prosecution and criminal proceedings. Offenders who confess to their crimes and express regret and a desire to reform are generally trusted to do so, by police, judges and the public at large. One criminologist writes that:

the vast majority [of those prosecuted] . . . confess, display repentance, negotiate for their victims’ pardon and submit to the mercy of the authorities. In return they are treated with extraordinary leniency.

250

, p. 495

Many custodial sentences are suspended, even for serious crimes that in other countries would lead to long mandatory sentences. Apparently, most prison inmates agree that their sentences are appropriate. Prisoners are housed in sleeping rooms holding up to eight people, and meals are taken in these small group settings. Prisoners work a forty-hour week and have access to training and recreational activities. Discipline is strict, with exact rules of conduct, but this seems to serve to maintain a calm atmosphere rather than provoke an aggressive reaction. Prison staff are expected to act as moral educators and lay counsellors as well as guards.

The picture is far starker in the prison systems of the USA. The harshness of the US prison systems at federal, state and county levels has led to repeated condemnations by such bodies as Amnesty International,

251

–

252

Human Rights Watch

253

–

254

and the United Nations Committee against Torture.

255

Their concerns relate to such practices as the incarceration of children in adult prisons, the treatment of the mentally ill and learning disabled, the prevalence of sexual assaults within prisons, the shackling of women inmates during childbirth, the use of electro-shock devices to control prisoners, the use of prolonged solitary confinement and the brutality and ill-treatment sometimes perpetrated by police and prison guards, particularly against ethnic minorities, migrants and homosexuals.

Eminent American criminologist John Irwin has spent time studying high-security prisons, county jails and Solano State Prison in California, a medium-security facility housing around 6,000 prisoners, where prisoners are crowded together, with very limited access to recreation facilities or education, training or substance abuse programmes.

256

He describes serious psychological harm done to prisoners, and their difficulties in coping with the world outside when released, across all security levels and types of institutions.

In some prisons, inmates are denied recreational activities, including television and sport activities. In others, prisoners have to pay for health care, as well as room and board. Some have brought back ‘prison stripe’ uniforms and chain gangs. ‘America’s toughest sheriff’, Joe Arpaio, has become famous for his ‘tent city’ county jail in the Arizona desert, where prisoners live under canvas, despite temperatures that can rise to 130°F, and are fed on meals costing less than 10p (20 cents) per head.

257

–

258

America’s development of the ‘supermax’ prison,

201

facilities designed to create a permanent state of social isolation, has been condemned by the United Nations Committee on Torture.

255

Sometimes free-standing, but sometimes constructed as ‘prisons-within-prisons’, these are facilities where prisoners are kept in solitary confinement for twenty-three hours out of every day. Inmates leave their cells only for solitary exercise or showers. Medical anthropologist Lorna

Rhodes, who has worked in a supermax, describes prisoners’ lives as characterized by ‘lack of movement, stimulation and social contact’.

259

Prisoners kept in such conditions often are (or become) mentally ill and are unprepared for eventual release: they have no meaningful work, get no training or education. Estimates vary, but as many as 40,000 people may be imprisoned under these conditions, and new supermax prisons continue to be built.

There is, of course, considerable variation in prison regimes within the USA. A recent report by the Committee on Safety and Abuse in America’s prisons gives a comprehensive picture of the problems of the system, and describes some of the more humane systems and practices.

260

A health care initiative in Massachusetts provides continuity of care for prisoners within prison and in the community after their release. Maryland has an exemplary programme for screening inmates for mental illness. Vermont ensures that prisoners have access to low-cost telephone calls to maintain their contacts with the outside world. And in Minnesota there is a high-security prison that emphasizes human contact, natural light and sensory stimulation, regular exercise and the need to treat inmates with dignity and respect. If you look back at Figure 11.2, you can see that most of these examples come from among the more equal US states.

Not only do the higher rates of imprisonment in more unequal societies seem to reflect more punitive sentencing rather than crime rates, but both the harshness of the prison systems and use of capital punishment point in the same direction.

DOES PRISON WORK?

Perhaps a high rate of imprisonment, and a harsh system for dealing with criminals would seem worthwhile if prison worked to deter crime and protect the public.

*

Instead, the consensus among experts worldwide seems to be that it doesn’t work very well.

261

–

264

Prison psychiatrist James Gilligan says that the ‘

most effective way to turn a non-violent person into a violent one is to send him to prison

’.

201

, p. 117

In fact, imprisonment doesn’t seem to work as well now as it used to in the US: parole violation and repeat offending are an increasing factor in the growth of imprisonment rates. Between 1980 and 1996, prison admissions for parole violations rose from 18 per cent to 35 per cent.

238

Long sentences seem to be less of a deterrent than higher conviction rates, and the longer someone is incarcerated, the harder it is for them to adapt to life outside. Gilligan says that: