The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger (40 page)

Read The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger Online

Authors: Richard Wilkinson,Kate Pickett

Tags: #Social Science, #Economics, #General, #Economic Conditions, #Political Science, #Business & Economics

At this stage, creating the political will to make society more equal is more important than pinning our colours to a particular set of policies to reduce inequality. Political will is dependent on the development of a vision of a better society which is both achievable and inspiring. We hope we have shown that there is a better society to be won: a more equal society in which people are less divided by status and hierarchy; a society in which we regain a sense of community, in which we overcome the threat of global warming, in which we own and control our work democratically as part of a community of colleagues, and share in the benefits of a growing non-monetized sector of the economy. Nor is this a utopian dream: the evidence shows that even small decreases in inequality, already a reality in some rich market democracies, make a very important difference to the quality of life. The task is now to develop a politics based on a recognition of the kind of society we need to create and committed to making use of the institutional and technological opportunities to realize it.

A better society will not happen automatically, regardless of whether or not we work for it. We can fail to prevent catastrophic global warming, we can allow our societies to become increasingly anti-social and fail to understand the processes involved. We can fail to stand up to the tiny minority of the rich whose misplaced idea of self-interest makes them feel threatened by a more democratic and egalitarian world. There will be problems and disagreements on the way – as there always have been in the struggle for progress – but, with a broad conception of where we are going, the necessary changes can be made.

After several decades in which we have lived with the oppressive sense that there is no alternative to the social and environmental failure of modern societies, we can now regain the sense of optimism which comes from knowing that the problems can be solved. We know that greater equality will help us rein in consumerism and ease the introduction of policies to tackle global warming. We can see how the development of modern technology makes profit-making institutions appear increasingly anti-social as they find themselves threatened by the rapidly expanding potential for public good which new technology offers. We are on the verge of creating a qualitatively better and more truly sociable society for all.

To sustain the necessary political will, we must remember that it falls to our generation to make one of the biggest transformations in human history. We have seen that the rich countries have got to the end of the really important contributions which economic growth can make to the quality of life and also that our future lies in improving the quality of the social environment in our societies. The role of this book is to point out that greater equality is the material foundation on which better social relations are built.

HOW WE CHOSE COUNTRIES FOR

OUR INTERNATIONAL COMPARISONS

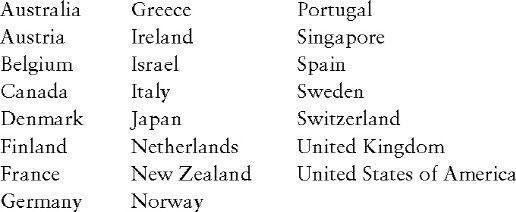

First, we obtained a list of the 50 richest countries in the world from the World Bank. The report we used was published in 2004 and is based on data from 2002.

Then we excluded countries with populations below 3 million, because we didn’t want to include tax havens like the Cayman Islands and Monaco. And we excluded countries without good information on income inequality, such as Iceland.

That left us with 23 rich countries:

CALCULATING THE INDEX OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL PROBLEMS

Not all of the countries in our data set had data for all the health and social problems listed on p. 19, but 21 of them had data on at least 8 of the 9. We include all these countries in our Index of Health and Social Problems (IHSP). Israel had only 6 and Singapore only 5 indicators, so they are not included in the Index, but are included in Chapters 4–12 whenever data permits.

The IHSP for the 50 US states was calculated using 9 variables rather than all 10 because there were no data on social mobility. Forty states have complete data for the 9 variables. Trust (from the General Social Survey) was missing for 9 states, and one did not have homicide data.

We calculated the z-scores of each indicator for each society, added up the z-scores for all the variables available for each society, and divided by the number of variables available. So a society’s score in the IHSP is the average z-score for the variables available for it.

Each component of the IHSP is therefore weighted equally.

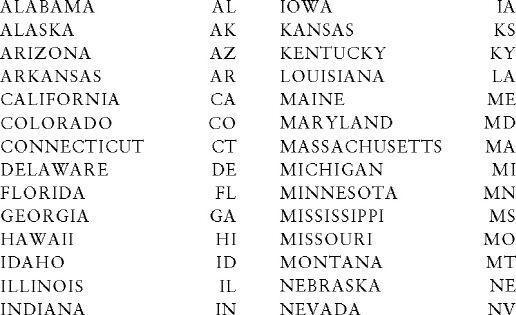

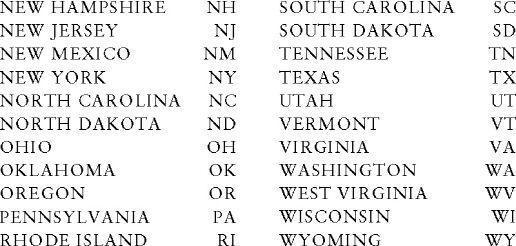

THE 50 AMERICAN STATES

In our figures, we label each American state with the two-letter abbreviation used by the US Postal Service. As these will be unfamiliar to some international readers, here is a list of the states and their labels:

1

. The Harwood Group,

Yearning for Balance: Views of Americans on consumption, materialism, and the environment.

Takoma Park, MD:Merck Family Fund, 1995.

2

. United Nations Development Program,

Human Development Report

. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

3

. R. Layard,

Happiness

. London: Allen Lane, 2005.

4

. World Bank,

World Development Report 1993: Investing in health

. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

5

. European Values Study Group and World Values Survey Association, European and World Values Survey Integrated Data File, 1999–2001, Release 1. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, 2005.

6

. United Nations Development Program,

Human Development Report

. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

7

. G. D. Smith, J. D. Neaton, D. Wentworth, R. Stamler and J. Stamler, ‘Socioeconomic differentials in mortality risk among men screened for the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial: I. White men’,

American Journal of Public Health

(1996) 86 (4): 486–96.

8

. R. G. Wilkinson and K. E. Pickett, ‘Income inequality and socioeconomic gradients in mortality’,

American Journal of Public Health

(2008) 98 (4): 699–704.

9

. L. McLaren, ‘Socioeconomic status and obesity’,

Epidemiologic Review

(2007) 29: 29–48.

10

. R. G. Wilkinson and K. E. Pickett, ‘Income inequality and population health: a review and explanation of the evidence’,

Social Science and Medicine

(2006) 62 (7): 1768–84.

11

. J. M. Twenge, ‘The age of anxiety? Birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952–1993’,

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology

(2007) 79 (6): 1007–21.

12

. M. Rutter and D. J. Smith,

Psychosocial Disorders in Young People:

Time trends and their causes

. Chichester: Wiley, 1995.

13

. S. Collishaw, B. Maughan, R. Goodman and A. Pickles, ‘Time trends in adolescent mental health’,

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry

(2004) 45 (8): 1350–62.

14

. B. Maughan, A. C. Iervolino and S. Collishaw, ‘Time trends in child and adolescent mental disorders’,

Current Opinion in Psychiatry

(2005) 18 (4): 381–5.

15

. J. M. Twenge,

Generation Me

. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006.

16

. S. S. Dickerson and M. E. Kemeny, ‘Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research’,

Psychological Bulletin

(2004) 130 (3): 355–91.

17

. T. J. Scheff, ‘Shame and conformity: the defense-emotion system’,

American Sociological Review

(1988) 53: 395–406.

18

. H. B. Lewis,

The Role of Shame in Symptom Formation

. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum, 1987.

19

. R. W. Emerson,

Conduct of Life

. New York: Cosimo, 2007.

20

. A. Kalma, ‘Hierarchisation and dominance assessment at first glance’,

European Journal of Social Psychology

(1991) 21 (2): 165–81.

21

. F. Lim, M. H. Bond and M. K. Bond, ‘Linking societal and psychological factors to homicide rates across nations’,

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology

(2005) 36 (5): 515–36.

22

. S. Kitayama, H. R. Markus, H. Matsumoto and V. Norasakkunkit, ‘Individual and collective processes in the construction of the self: self-enhancement in the United States and self-criticism in Japan’,

Journal of Personal and Social Psychology

(1997) 72 (6): 1245–67.

23

. A. de Tocqueville,

Democracy in America

. London: Penguin, 2003.

24

. National Opinion Research Center,

General Social Survey

. Chicago: NORC, 1999–2004.

25

. R. D. Putnam,

Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community

. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

26

. R. D. Putnam, ‘Social capital: measurement and consequences’,

ISUMA: Canadian Journal of Policy Research

(2001) 2 (1): 41–51.

27

. E. Uslaner,

The Moral Foundations of Trust.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

28

. B. Rothstein and E. Uslaner, ‘All for all: equality, corruption and social trust’,

World Politics

(2005) 58: 41–72.

29

. J. C. Barefoot, K. E. Maynard, J. C. Beckham, B. H. Brummett, K. Hooker and I. C. Siegler, ‘Trust, health, and longevity’,

Journal of Behavioral Medicine

(1998) 21 (6): 517–26.

30

. S. V. Subramanian, D. J. Kim and I. Kawachi, ‘Social trust and self-rated health in US communities: a multilevel analysis’,

Journal of Urban Health

(2002) 79 (4, Suppl. 1): S21–34.

31

. E. Klinenberg,

Heat Wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago

. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2002.

32

. J. Lauer, ‘Driven to extremes: fear of crime and the rise of the sport utility vehicle in the United States’,

Crime, Media, Culture

(2005) 1: 149–68.

33

. K. Bradsher, ‘The latest fashion: fear-of-crime design’,

New York Times

, 23 July 2000.