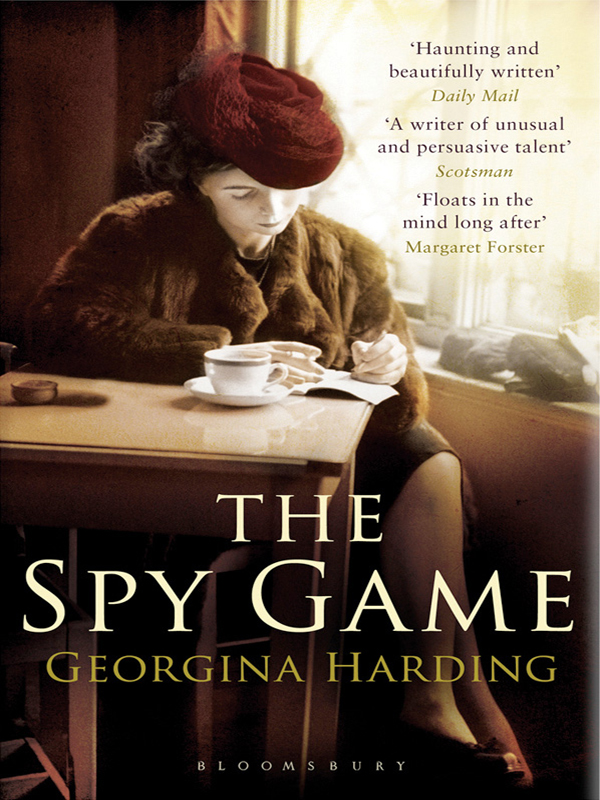

The Spy Game

Authors: Georgina Harding

THE SPY GAME

GEORGINA HARDING

is the author of the novel

The Solitude of Thomas Cave

and two works of non-fiction:

Tranquebar: A Season in South India

and

In Another Europe.

She lives in London and the Stour Valley.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Tranquebar: A Season in South India

In Another Europe

The Solitude of Thomas Cave

THE SPY GAME

GEORGINA HARDING

_ocr-3.jpg)

First published in Great Britain 2009

Copyright © Georgina Harding

This electronic edition published 2009 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

The right of Georgina Harding to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 36 Soho Square, London W1D 3QY

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 978-1-60819-147-5

www.bloomsbury.com/georginaharding

Visit

www.bloomsbury.com

to find out more about our authors and their books.

You will find extracts, authors interviews, author events and you can sign up for newsletters to be the first to hear about our latest releases and special offers.

For Nellie,

and for Kay

F

og that morning, a freezing fog; the flagstones dark and slippery outside the door. I shall always associate my mother with

fog. Once she went up to London in one of the last peasoupers, I cannot have been more than six then, and came back on the

train late. She drove home and came in beneath the bright overhead light in the hall and talked about it, and when she took

off her silk headscarf I thought that I saw a remnant of the fog shaken off it, a dull spray that fell away off the gleam

of the silk. I saw it like a horror.

It was there, I told her. The smog. She had brought it home.

My mother looked in the hall mirror as if to check, smiled a dazzling smile into the glass and shaped up her hair where it

had been flattened by the scarf.

'All gone now.'

The smog in London had a greenish-yellowish colour because of the poison it contained, that made you cough if you did not

wear a mask and made fragile people die. The smog was famous so you remembered when people talked about it.

The fog at home was plain grey country fog, dead leaves and cow smell in it and the hollow sound of milking in the farm across

the road. No poison there but numbness, a numbness that you knew from other, forgotten days, that seeped into grass and wood

and stone and skin, and made them all the same, until feeling was gone along with the sight of the village and the valley

and the hills, as if these no longer existed and there was only this one numb place and no other to be known.

And yet the hills were there, even if I could not see them. I knew that they were there; and close, not remote at all. The

road rose steeply out where the houses ended, up round bends and through close woods to the ridge and the high open land beyond

it. Up there on the fog-covered hills there would be ice, on the surfaces of the roads that had been wet yesterday with all

the week's rain, hidden ribbons of ice on the slopes, on the bends where water had run down in black streams on the asphalt.

There was a skin of ice on the dips in the stone path. Later I would go out in my boots and smash it like glass but now I

stood huddled on the step still warm from bed and felt the cold on my bare face and through the soles of my slippers, penetrating

and pushing away the sleep.

'Don't stand out there, Anna, you will catch your death.' The ineradicable pattern of German in my mother's voice. 'Run on

in and get dressed.'

Cold, waking me up. A Monday in January during the Cold War. A sting in the air that touched closer than the kiss she gave

me, which was no more than a brush of breath and powdered cheek, and a pursing of new red lips just so far from the skin as

to leave no mark, and I stood in my slippers on the doorstep and had already as a memory or a dream the waxy scented smell

of her as she started up the car and ran it awhile with the exhaust puffing while she scraped windscreen and windows, and

then got in and closed the door and seemed to wave, though the scraped patch was small and it was hard to see, and drove away.

Her lights were gone, into the cold.

What I did next was done with the deliberateness of a child suddenly responsible for herself. I went back in as I had been

told, pushing the big bolt across the bottom of the front door that I must not open to strangers. I finished a bowl of Rice

Krispies that had grown soggy and then went upstairs and again I did as I had been told. I put on a warm vest and long socks

and jeans. There was a green mohair jumper that I kept after that for years, until it was too small and worn through in places

and dangled broken threads that caught in things, but I would not let it go. I put it on that morning because of the cold.

Later I would wear it in almost any weather. I folded my pyjamas and put them under the pillow, tidied the bed and pulled

up the bed-spread, arranged my animals upon it. From downstairs came the clumsy sound of Margaret doing the cleaning, moving

things round as she dusted the sitting room. (Useless girl, my mother would say, stroking the top of some table and inspecting

the dust that collected on her fingertips. Has she no eyes with which to see?)I slipped by, slipped down past the open door

to the room, where Margaret had her back turned and was unwinding the cord of the Hoover. I found my satchel in the kitchen,

took my coat from its hook in the hall and let myself out at the back, pulling out the mittens and hat that were stuffed in

the pockets and shoving them on soon as the cold hit. I walked to Susan's, walked fast in spite of the fog, head down, scarcely

needing to see the way as I walked it so often, around the side of the house, down the stone path and along the road, and

then through the gate into her front garden, and the fog was thick and the ice was thin, scrunching into mud underfoot, and

Mrs Lacey let me in as she always did and a little later we drove to school. Mrs Lacey drove slowly, rubbing the windscreen

and leaning forward over the steering wheel as if those few inches made all the difference to what she could see. And all

day the fog held. It was there like a milky breath beyond the classroom windows, at break, at lunch, when Mrs Lacey took us

back at the end of the day, the headlamps lighting it before the car. Even when it got dark and the fire was lit and the curtains

were drawn, I knew that the fog was there.

The Times, Monday 9 Januay 1961. Price sixpence.

(Going back now, going over these things, I read the newspapers for that day.) The front page is given over to the Classifieds.

How faceless it was then, the front page of

The Times,

a full broadsheet page of solid type, small-type lists cramped across seven tight columns: Births, Marriages, Deaths, Personal

(and yet how impersonal), Motor Cars Etc., Shipping, Agriculture.

PALMER on

7

Januay 1961, peacefully, after an accident, HILDA BEATRICE, widow of Lieut. Col. C. H.

PALMER

. . .

Notice of a ship of the Blue Star Line disembarking London via Lisbon for Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina, exclusively first-class.

The news does not begin to appear until page six.

Two Climbers Found Dead. Union Plan for Car Industry. Child Drowns in Roadwork Trench.

The Portland story is slipped in amongst the rest.

Victoy Assured for President de Gaulle.

Five People on Semets Act Charge. General McKeown in Leopoldville.

It runs to a few standard phrases, no more. The reporting is quaintly dated: the plain headlines, the conventional formulations,

the formality with which people are named, the images which are pinched and small, head-and-shoulders photographs mainly of

the Prime Minister and dignitaries and people with titles. All of it is respectful, restrained, clipped like the BBC voices

of the time, drilled in objectivity.

Suspects charged under the Official Secrets Act, held at Bow Street Police Station

. . .

The same news must have been on the radio that morning. It is possible that my mother heard it in the kitchen before she left,

but she was early and in a rush, so it is more likely that she would have heard it in the car as she drove. There is nowhere

lonelier than a car in a thick fog. She would have had the radio on for company, driving so slowly that every turn in the

known road seemed alien to her, delayed, out of place, the lights of oncoming cars looming weirdly towards her, the road surface

revealing itself too late, having of necessity to be trusted. She would have heard the voices in the background as she concentrated

on where she was going, looking for some movement in the air, hoping that the fog would lift on the hilltops or across the

next valley or when the hills were passed.

The Times'

forecast has the fog in the west of England dense but clearing slowly; the roads icy at first; the wind light, variable.

I remember no wind, and the fog did not clear. In Gloucestershire where I spent that day the air remained entirely still,

as if it was a day that didn't happen.

If someone had told me that it was a day that I must remember always, I would of course have made it different. I was old

enough to know the conventions of these things. If for example my mother had been a soldier and there had been a proper war,

then I would have stood at the door and marked it all. (And if she had not been who she was, and if she was on the right side.)

I would have marked the shine in her eyes, the braveness of her smile, the set of her shoulders in the big tweed coat. I would

have stood that extra moment gazing into the fog after the car's red lights had melted into it; made a picture for my memory

of a tall pale girl in a dressing gown, pink slippers and a warm bed behind her but no one else in the house.

And after, I would have not have gone to school but stayed at home. Just myself, alone. No Margaret there to flatten the atmosphere.

There was something so mundane about Margaret - mundane was a new word, one that I had heard Mrs Lacey say in her high, ringing

voice, and I had held it though I was not quite sure of its meaning and applied it to Margaret, Margaret with her heaviness

and her thick legs and her acne. To be eight years old, just a few days over eight and alone in the house would have been

much finer.

I would have done something solitary. I would have taken out some cards and sat down on the carpet in the sitting room and

played patience. Mrs Lacey had taught us to play a game of patience that she called Chinaman. She said that in Singapore there

was a Chinaman who sat on the street and invited you to play the game, and you paid him money and he gave you the pack of

cards, and if you got more than thirteen cards out he gave you the money back and you kept the cards as well, and you had

won. That didn't sound so many, thirteen, but it was hard to get. Mrs Lacey said that it was to do with odds. The Chinaman

was good at sums and could work out the odds. He wouldn't sit out on the street and play the game if he did not know that

he would mostly win. And yet every now and then the odds fell in the player's favour, and that made you feel good. So I would

lay out the cards, seven along with the first upturned, six the next line, and so on, and play the game through, and when

I had worked down the pack once - just once, the Chinaman was strict about that and to go on would be cheating - I would gather

the cards up and shuffle and deal once more.

Again and again, until the game came out, I would lay the lines of cards against the pattern of the Persian rug before the

fire, and the fire would be burning (some invisible hand must have been there to light it for me) and there would be the glow

of the fire and the circle of light from the lamp, or perhaps, as the day passed, clearing slowly, a low beam of winter sun

breaking through the grey beyond the window.

I'd deal the cards and they'd go down crisp. I'd gather them up and deal again. All the time I would have known that at any

moment the policeman might come, or the postman, some man in uniform with the news in him, holding the words back like he

held his bicycle, like you'd hold back a young dog from a stranger; and the fair-haired girl who stood at the door (a heroine

to myself, having a quality of calm and self-possession beyond given age) would have known at once what words they were by

the look in his face.

If she had been a soldier, it would have been black-and-white; black-and-white like the postman's telegram, be-cause this

after all was 1961, because I was eight, because war was the confrontation of good and evil and the soldiers on our side were

heroes, because I watched television, because we did not have colour then. Clear-cut, not the muddle it became: the hanging

around at the Laceys' house long after school, the staying for tea - though that in itself was nothing strange, I was often

there for tea - the being there even after Mr Lacey came home and poured his gin and tonic and turned on the News while the

phone rang, then having a bed made up in Susan's room and staying the night. Your parents won't be back till late, they want

you to stay here with us. And all that evening beneath the surface, the knowledge of something big unspoken, of the falseness

of smiles and the coding of words.