The Star of the Sea (49 page)

Read The Star of the Sea Online

Authors: Joseph O'Connor

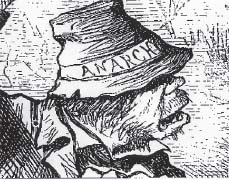

‘Comparative Anthropology’ by Daniel Macintosh

The Anthropological Review

, January 1866

THE GUEST OF HONOUR

T

HE

TWENTY-FOURTH

DAY OF THE

V

OYAGE

(

THAT BEING

WEDNESDAY

THE FIRST DAY OF

DECEMBER);

IN WHICH THE

R

EADER IS OFFERED A

NUMBER OF

C

ONTEMPORANEOUS DOCUMENTS; ALSO THE

TRUE RECOLLECTIONS

OF SOME OF THE

P

ASSENGERS

PERTAINING TO THE

EXTREMELY IMPORTANT

EVENTS

OF THAT DAY; AND THE

A

UTHOR’S OWN

A

CCOUNT OF A

DISTURBING

B

IRTHDAY

C

ELEBRATION (WHICH LATTER HE

WILL NEVER

F

ORGET SO LONG AS HE

L

IVES)

.

Captain Lockwood’s Quarters

— 9.38 a.m. —

An Emergency Note in the Register

CALENDS DEC. 47

I have not five minutes ago compleated a conference of myself, First Mate Leeson, the prisoner Pius Mulvey and Lord Kingscourt. The circumstances in which the interview occurred were as follows:

Two hours erewhile, at dawn this morning, I received word that my presence was required in the lock-up. The prisoner Mulvey was in a state of profound distress all night. He said he needed pressingly to speak to myself and to Lord Kingscourt about a very dark matter indeed. He would not reveal it then and there but intimated that he had happened upon extremely troubling information touching the safety of Lord Kingscourt and his family aboard this vessel.

I gave orders for him to be conveyed to my quarters. There he refused to breathe another syllable until Lord Kingscourt was brought to him in person. I was obviously averse to arrange for this but he said he would say nothing (and indeed would return to the

lock-up, taking his information with him) if he could not see His Lordship and speak to him in person.

Contriving a pretext so as not to cause alarm I sent a message to Lord Kingscourt’s quarters and asked if he would breakfast with me. When he came in, Mulvey became quite distraught. He fell to his knees and began to exclaim, kissing the hands and garments of Lord Kingscourt, invoking the name of his late mother as that of a holy personage. His Lordship appeared disconcerted by such an effusion and asked the other to stand up. I explained to Lord Kingscourt that this was the man of whom I had spoken previously, who had asseverated a great fidelity to the Merridith family.

Mulvey told us that last evening at approximately midnight he had been looking out the bars of the lock-up when he had perceived two men of steerage passing by on the deck. They had paused nearby and commenced to mutter and whisper.

One confided to the other that he belonged to a secret revolutionary society, namely ‘The Else-Be-Liable Men’ of Galway. And he revealed that he had been placed on board the ship in order to murder Lord Kingscourt and his wife and children as a revenge for evictions and other deeds carried out by the Merridith family in that unhappy district.

Lord Kingscourt was very greatly shocked; but he then said that he had indeed received threatening notes from the same hooligan gang in the past. Moreover he mentioned that he had reason to believe his father’s grave to have been desecrated by these very barbarians and that he had been advised by the Irish Constabulary not to travel through his Estate without an armed bodyguard. He was exceeding concerned that his wife and children should be protected on the ship. I guaranteed to him that I would order personal guards from this on. He implored me to do so in such a way that his wife and children should remain unaware of the situation, since he did not want them to be upset. I said it were better if they remained in quarters for the rest of the voyage; and he said he would see what might be done about it.

One of the conspirators Mulvey was not able to distinguish; but the other that had spoken of dastardly murder he named as Shaymus Meadowes, lately of Clifden.

Immediately I sent Leeson and a number of men down to

steerage to arrest him. A meticulous investigation was made of his belongings and therein was found a sample of revolutionary literature, that is, the words of a hateful ballad about landlords which a number of the men have heard him singing late at night when he was drunk. He has been placed in the lock-up until we arrive at New York, at which time he will be given into the custody of the authorities.

Lord Kingscourt thanked Mulvey most sincerely for what he had done and pronounced himself greatly in the latter’s debt. He said he understood that it must have been difficult, knowing very well the informer was regarded among the commoner Irish as a pariah. He offered Mulvey a reward for his courage but it was insistently refused. Mulvey said he had done nothing other than his Christian duty, that he should not have been able to sleep at night had he taken any other course. Again the memory of Lord Kingscourt’s mother was mentioned, Mulvey revealing that his own parents had benefited from her kindness on one occasion and often prayed for her repose still and once a year visited her grave at Clifden. (Queer; I had thought his mother to be deceased.) That a picture of the late Countess hung to this day in their humble cottage, a devotional candle burning constantly before it. That one of his own sisters had been christened ‘Verity’ in veneration of the memory of Lord Kingscourt’s mother. That to allow Lady Verity’s son to be murdered by a reprobate such as Shaymus Meadowes would be unrealisable for him. And that the thought of the two little boys being harmed or worse was simply more than he could bear to countenance.

At that point Lord Kingscourt became very distressed. Mulvey begged him not be sad but rather to believe that the great majority of Galwaymen would feel the way which he, Mulvey, did but that there was always one rotten apple in the orchard to get all the others a bad name. He said poverty and forgetting their faith had created such a hardship among the people that violence had sadly sprouted in that barren field where before was the naturally existing friendship between humble servant and sheltering master. Lord Kingscourt thanked him again and collected himself a little.

At that point it occurred to Lord Kingscourt that Meadowes being in the lock-up, and steerage being no sort of possible haven,

there was no safe place on the ship for Mulvey to go to. ‘I suppose that is true,’ Mulvey replied. ‘I had not thought about it. But it is all in the hands of the Saviour, may His will be done always. He will protect me, I know.’ And he added: ‘If I am murdered for what I am after doing this day, at least I can die with my conscience unsullied. And I know I shall see your mother in Paradise this night.’

I said I could perhaps offer him a berth among the men, but Lord Kingscourt would absolutely not hear of it. He said it was not every day that a man had his life saved and he meant to show at least some variety of gratitude for it. His Lordship and Mulvey agreed with myself that he would be accommodated in the First-Class quarters for the remainder of the voyage; in a lazaretto next to Lord Kingscourt’s own stateroom which is used for the storing of linens and such. A subterfuge was agreed by which such an arrangement might be cloaked.

He, Lord Kingscourt, said he would need a short time to discuss it with his wife. (Her Ladyship, it appears, is the wearer of the britches.)

Countess Kingscourt’s Cabin

— about 10 a.m. —

‘You’re not serious,’ Laura Merridith said.

‘It is tiresome, I know. But Lockwood insists the poor chap is at death’s door.’

‘Precisely, David.’

‘What does “precisely” mean?’

‘He could have cholera or typhus: any kind of filthy infection. And you propose to allow him to sleep next to our children?’

‘Hardly next to them, for pity’s sake.’

‘In the cabin next door, then. And across from my own. How, convenient, should he require a trio of companions for bridge.’

‘Will you never understand that we have a responsibility to these people?’

‘I have done nothing to “these people”, David. And they have done rather a lot to me.’

‘I will help an unfortunate man who is down on his luck. With or without your blessing, Laura.’

‘Then do it without!’ she shouted. ‘As you do everything else.’

She went to the porthole and stared out hard, as though she expected she might see land from a distance of five hundred miles.

‘Laura – surely we can conduct ourselves without raising our voices.’

‘Oh yes. I forgot. We must never raise our voices, must we? Must never have a single human emotion about anything. Must insist on the same bloodlessness and lifelessness as one of your father’s damned skeletons.’

‘I had rather you did not turn these quarters into a barrack-room with your language, Laura. And what we must do is to think of the boys. You know they find it upsetting when we have words.’

‘Do not presume to give me instruction on my children, David, I warn you.’

‘I would never do that. But you know I am right.’

She spoke over her shoulder, as though he wasn’t worth the effort of facing. ‘How would you know what they find upsetting? Is it you they come to when they are upset? Their father who cares more for individuals he does not know than he does for his own wife and family.’

‘That is not fair.’

‘Is it not? Are you aware that today is your eldest son’s birthday? It would not have hurt you very much to mention it to him if you were.’

‘I’m sorry. You are right. I had momentarily forgotten.’

‘You might rather say sorry to the person your thoughtlessness has hurt. When you have quite finished saving the world from itself, of course.’

‘They are dying in tens of thousands, Laura. We cannot do nothing.’

She made no reply.

‘Laura,’ he said, and he made to touch her hair. As though sensing the gesture, she moved to avoid it.

‘It will not trouble us to help a little, Laura. Surely you can agree. We shall be in New York in only three days.’

She spoke very quietly, as though it hurt her to speak. ‘They’ll

never love you, David. Why can’t you see it? Too much has already happened for that.’