The Steel Wave (26 page)

Authors: Jeff Shaara

He moved to his desk, opened a small notebook, flipped a page, smiled.

“This could be perfect timing, perfect. This will please her enormously.”

“Sir?”

“Put that paperwork aside for the moment. I want you to arrange a trip for me. Official business, of course. With the weather this poor, I will take the opportunity to visit the Führer to discuss our progress. He continues to send me his heartiest compliments on our work here, so perhaps this time I can make use of his good spirits to convince him to listen to my strategies. But I want you to schedule the transportation to allow me a couple days in Herrlingen. I can leave even today. The Führer is presently at Berchtesgaden, which is but a short journey from my home. Yes, she will be greatly surprised and greatly pleased if I am there. This weather has opened the door. It is perfect timing.”

“If I may ask, sir, is it a special occasion?”

“Quite special. I have been instructed not to reveal this, you understand.”

Speidel smiled. “Anniversary, sir?”

“Not quite. Lucie is turning fifty. Her birthday is only two days away, on June sixth.”

16. ADAMS

SPANHOE AIRFIELD, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE

JUNE 5, 1944, 11 P.M.

T

he day had passed with painful slowness, the natural letdown from so much adrenaline the night before. It was every veteran’s nightmare, that once the call came, you geared yourself into that mindless mode, moving with precision, relying on the automatic memory from so much training, from having done it all before. But then the mission had been aborted. He had climbed out of the C-47 in a haze of despair, cursing as they all cursed, but the weather had turned truly awful, a hard blowing rain that soaked them through their jumpsuits.

The officers had hustled them quickly into the hangars, most of the men sleeping right there, on a vast sea of cots that had been set up days before. Spanhoe was the home for the 315th Troop Carrier Group, one part of the enormous armada of transports that would ferry the paratroopers and gliders into France. The paratroopers of the 505th had been hauled company by company to Spanhoe, one of several airfields where the C-47s would begin the mission, but this one was nothing like Adams had seen before. There were no sleeping quarters, no mess hall. What barracks there were at Spanhoe were already occupied by the huge number of ground and flight crews, so the paratroopers had slept in the hangars. The men groused, but only for a while, their attention caught more by the vast parade of C-47s that continued to land, coming in from airfields throughout England, great flocks of green birds, gathering in long rows along the various landing strips.

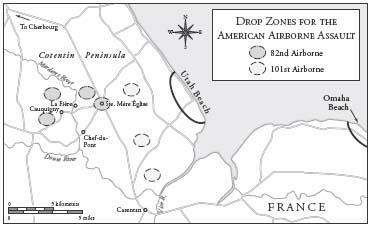

Their briefings had been more intimate this time, down to the company and platoon level, senior officers passing along detailed instructions to their subordinates, junior officers passing those details to the noncoms. Captain Scofield had gathered his company’s lieutenants and noncoms into a cramped recreation room, the first time since Adams had served on Gavin’s staff that he had been privy to a map of their part of the operation. It was the familiar shape of the Cotentin Peninsula, but now the map was marked in red: the angular, circuitous routes the transports would fly to sweep into France from the west, which Adams thought was someone’s very good idea, staying far away from the naval ships along the invasion beaches. There were circles on the map as well, the drop zones, inland from where the American Fourth Division would push ashore, at the place someone had named Utah Beach.

Adams had seen these kinds of maps a year before, drop zones neatly circled on the maps of Sicily. Then, the perfectly precise plans on paper had become a disastrous comedy of bad weather and inept flying, green pilots scattering their paratroopers over a sixty mile swath of Sicilian countryside. But the paratroopers, led by men like Jim Gavin, had turned the disaster into victory: They had held the immense power of German armor back away from those landing beaches, allowing the infantry to come ashore and establish the critical beachheads. Now, the paratroopers had been asked to do it again, but this time, the numbers were immense. Instead of the three thousand who had made the first drop in Sicily, in Normandy the Americans would drop fourteen thousand men, two full divisions. Whether or not the pilots would do a better job of finding the drop zones was a question Adams tried not to think about.

The night before, they had gone through their usual preparation, blackening their faces and loading themselves down with more than a hundred pounds of equipment, from weapons to toilet paper. But first there had been another custom to observe: the evening meal, a spectacular bounty of fried chicken and gravy, fresh vegetables, and mashed potatoes that Adams swore had been drenched in butter, one of the rarest commodities of the war. The jokes had come, of course, their Last Supper, a final display of gratitude for men who were to begin an operation that would take them far from any kind of comforts.

When word came that the mission had been postponed, the mess officers had been as surprised as everyone else, and so one day later there was one more Last Supper, a chaotic affair tossed together by kitchen staffers at Spanhoe who scrambled and scrounged to find something for these two thousand men to eat, men who weren’t supposed to be there. Stew, Adams thought. That’s what they called it. They said it was beef, but who the hell knew? He rubbed a hand on his stomach, felt a rumble, but he couldn’t fault the mess staff. I felt the same way last night, and it wasn’t because I ate too much fried chicken. Nobody’s guts are working too well right now.

“Line up here! If you can haul it, you need it!”

The men obeyed, Adams bringing up the rear of the line. In front of him, men pushed past tables and crates, loading up their pockets and belts, no one speaking except the ground crews, low voices, casual greetings, useless words of encouragement. The crews were handing out ammunition, grenades, and all the rest of the cumbersome gear the men would carry. There was no talking, none of the raucous kidding around, much of that exhausted the night before. The first time, it had been something of a ridiculous party, so many frayed nerves betrayed by bad jokes and off-key singing, especially the new men, but tonight even they were quiet, absorbing the urgency and the fear. There had been some effort to get a card game going, but no one had enthusiasm for it, the poker players seeming to understand that luck was something best saved for what might happen in the morning.

The men were making slow progress in front of him, but Adams wouldn’t be impatient, wouldn’t gripe at anyone. Then, off to one side, he suddenly heard a voice, one man singing.

“Give me some men who are stout-hearted men,who will fight for the right they adore.

Start me with ten who are stout-hearted men,and I’ll soon give you ten thousand mo-ore!”

Around him, his own men responded with puzzled annoyance, and Adams said aloud, “What the hell?”

He saw the singer now, slapping his buddies on the back, encouraging them to join in with him, some feeble voices rising, but not many.

“He’s trying to organize a full-blown glee club,” Adams said, to no one in particular. “Somebody needs to stuff a sock in his mouth. He must be one of the

brave ones,

all puffed up. Jackass.”

The man gave up his efforts, no one in his squad seeming interested in his one-man attempt to rally their patriotic energy. In front of Adams, the men continued to press forward along the tables and crates of equipment, the only sounds the clanking of metal, equipment fastened and hooked and lashed to each man’s jumpsuit. Adams looked out across the field, surprised he could still see, the darkness not yet complete. It was strange, something to do with British Double Summer Time, some odd way the British had of adjusting their clocks to make better use of daylight. Adams had never completely understood that; time was time. He looked at his watch. This late, it ought to be dark, he thought. I guess it makes sense to somebody who’s smarter than I am. That’s why I’m just a sergeant. He was suddenly aware of a voice tripping through his brain:

Give me some men who are stout-hearted men…

Oh, for God’s sake! That idiot has me singing his damned song. Think of something else. What, another song? He tried to silence the music, then thought, No, just let it go. You have enough to think about. He ran a hand over the Thompson hanging off his shoulder. Think about that. Grab a ton of ammo. These guys think they need rations more than anything else. He called out ahead.

“All right, you morons. Fewer chocolate bars and more grenades. If you think it’s too heavy, it’s not. The army’s not going to run out of this stuff.”

Shoulder to shoulder, and bolder and bolder…

Dammit! Shut the hell up! If that jerk had been one of my guys, I’d stick a grenade in his jumpsuit. Ten thousand men! That’s how many Krauts are waiting for us, at least. I wonder if the jackass who wrote the song thought of that.

“Keep moving!”

The words came from in front of him, Lieutenant Pullman, grimfaced, standing at one end of a large wooden box. Pullman would be jumpmaster of Adams’s plane, the last man out. Adams would be crew chief, an unusual role for him. The crew chief was the last man to board the plane, stayed close to the wide doorway, and so would be the first man to jump. Adams wasn’t used to that, was far more experienced being the thorn in the side of the hesitant jumpers, coming up from behind, pushing the man out the opening who might not be so eager to make the jump or, worse, yanking the man back, out of the way of the others. In training, if a man wouldn’t go, you could urge him, prod him, yell at him, but ultimately no one was forced to jump. This time, there would be no one returning home with the plane. In combat, there was a different kind of urgency, the power of the entire stick overwhelming any one man’s fear. If anyone froze, the surge of men behind him would solve the problem; no matter what terrors filled a man’s thoughts, he would find himself rammed out through the door, his chute yanked open automatically by the static line above his head. Adams had seen it before, that strange paralysis that could infect even experienced jumpers, men who would suddenly lose their nerve. Adams scanned the men around him. That wouldn’t be a problem, not with this bunch. He had an instinct for those men, one reason he had become such a good jumpmaster. You can tell who the problems are likely to be, he thought. Sometimes it’s the quiet ones, but mostly it’s the loudmouths, men like Marley. But he’ll be okay, they’ll all be okay tonight. He rubbed his stomach again, could taste the stew in his throat, cursed to himself. I hope that was beef. Damned English farmers. He recalled a lesson from Fort Benning, drilled into him from some textbook:

The anticipation of combat is far worse than the combat itself.

That’s a crock, but most of these boys don’t know that yet. Scared is healthy, means you’re paying attention. But nothing prepares a man for what he’ll see on the ground. How many of these loudmouths know what they’ll do when they see a Kraut pointing a bayonet at them? Like that moron over there, with his damned song?

And I’ll soon give you ten thousand mo-ore….

Dammit! That’s what we should do: Sing that to the Krauts. Win the war by driving them nuts.

He reached the tables, looked at Pullman, could see the lieutenant sweating in the chill, making anxious motions with his hands. Pullman pointed into the crate closest to him.

“Grab a couple of these, Sergeant. Gammon grenades. Most of the men have no idea how to use the things, but I want you to carry them. We might run into some armor.”

The grenades looked like bundles of socks, small black wads of cloth stuffed with pliable bricks of plastic explosive. To one side, Adams heard a voice: Marley, the big man already loaded up with a mountain of gear.

“Hey, Sarge, you ever use that stuff before?”

Adams stuffed one in a pocket on his pants leg. “Nope. Didn’t have them in Sicily. You saw a tank, you either fired a bazooka or ran like hell. We did a little of both.”

“You think we’re gonna run into tanks, Sarge?”

Marley had lowered his voice, and Adams realized it was a serious question, the joking bluster of the man erased by the mood of the men around him. The lieutenant responded.

“We might, Private. If we do, these Gammon grenades are made to stick to their bellies.”

“Sir, you mean…under? How do you get under a tank?”

Adams moved past Marley toward a box of magazines, ammunition for his Thompson.

Pullman said, “You let them come to you. If you’re in a foxhole, they’ll drive right over you. You just stay put and jab that thing up into the tank as it passes. It’s supposed to wedge into whatever crack you can find.”

Straight out of a training manual, Adams thought. He tried to respect Pullman, but the man had never seen combat. Adams had been in that exact situation in Sicily, a massive Tiger tank rolling up a hillside directly over a narrow foxhole. Then there were no Gammon grenades, nothing to stop the great steel monster. The only weapon was the bazooka, something most of the men had never fired or, worse, had never even seen. He glanced back at Pullman, saw him talking to Marley still, the tall heavy private seemingly eager to learn what he should already have learned in training. He can’t have forgotten all that, he thought. No, he’s just scared to death. Chattering. Maybe the lieutenant too. I wonder what either one of them will do if a tank drives over him?