The Steel Wave (58 page)

Authors: Jeff Shaara

“

G

eneral Gavin’s as pissed off as I’ve ever seen him.” Scofield took a drink from his canteen. “Probably as pissed off as

you’ve

ever seen him.”

Adams, his back against a tree, stared at the mess tent in the distance, trucks in a line on the road, men milling around, most holding plates of food. He shook his head. “Again?”

Scofield didn’t answer, chewed the corner off a thick cracker. Adams saw men gathering, talking, helmets in their hands, a larger crowd around one of the lieutenants. The captain’s news was spreading throughout the company, the men reacting with curses and numb shock, the entire camp building into more of an angry rabble than a regiment of soldiers. Adams reached down beside him, grabbed a tuft of dry grass, and pulled it up by the roots, a feeble show of anger, the most energy he could muster.

“What the hell’s wrong with the One-oh-one? They’ve been kicked as hard as we have. Aren’t they involved in this war too?”

“Not this time. Not here anyway. According to General Gavin, the One-oh-one has already been moved off the line. They’re up north, on the coast, Cherbourg’s new police department.” Scofield let out a breath. “Keep your mouth shut about that. You don’t need to know about our troop positions. I know better than to talk about that.”

“Don’t worry about it, Captain. I’m not drawing any maps, and no one in my platoon will hear a damned thing. I’d love to tell ’em though. Might fire ’em up.”

“Not funny, Sergeant. I heard enough cracks about that. Gavin was pretty steamed about Ridgway, something Ridgway told the higher-ups. Doesn’t matter how beat to hell we are, he said.

We might be weak in numbers, but our fighting spirit is unimpaired.

”

“Oh, for crying out loud. It’s Ridgway who’s impaired.”

“Can that, Sergeant. There’s already enough bitching about generals at Gavin’s CP. I don’t want to hear it from you.”

“I’m entitled, sir. How many men are in this damned army? We’ve lost—what, half our strength? And we’re all they have to make this attack?”

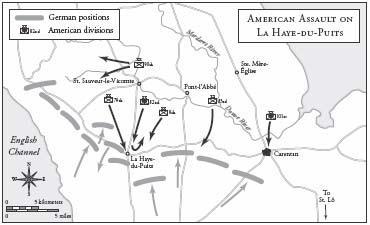

Scofield put a hand up. “Shut it! Now look, Sergeant, I hate this as much as anyone in this outfit, but we’ve got a job to do. Gather your platoon, and make sure they know what we’re doing. The Ninetieth will be on our left and the Seventy-ninth on our right. The Eighth is coming up behind us, and Gavin says they’ll replace us in line as soon as we reach our objective. But they need people leading the way who won’t stumble over their own feet. Like I said, Gavin’s madder than hell about this, and the division has made protests all the way to Bradley. But the orders come from the very top, and it doesn’t much matter what any of us think out here. We jump off at Oh-six-thirty, and advance toward a town called La Haye-du-Puits, about eight miles south of here. Colonel Ekman wants everybody rested, so make sure your guys get some sleep. No cards, no dice.”

“Who’s leading the advance?”

Scofield looked down, another long breath.

“That was Colonel Ekman’s decision. The Five-oh-seven is more beat up than we are, and most of the Five-oh-eight is already off the line. The Three-twenty-five hasn’t exactly impressed Gavin, and so, they’ll come in on our flank and rear, along with the Five-oh-seven.” He paused, and Adams waited for the words. “The Five-oh-five is the point.”

“Of course we are.”

SOUTH OF PONT-L’ABBÉ

JULY 3, 1944

The swamps and hedgerows were mostly behind them; the terrain now was wooded, the ground rolling, only a few grassy fields and pleasant farms. The roads were dismal, sloppy with mud, and the tired legs of the paratroopers made slow progress. Adams could feel the wetness in one of his socks, water seeping through a gash in the side of one boot, the same boots he had worn since the operation began. There had been no supply trucks for the personal needs of the men; most of the trucks they had seen brought K rations and tanks of drinkable water.

The ammunition trucks had been scarce as well, and Adams knew from the telltale tugging on his pants legs that he had only a half dozen magazines for the Thompson. For reasons no one explained, there had been ample supplies of grenades, the men scooping them up from habit and attaching them to their shirts without comment. Whether or not it was an accident, a chance delivery from the supply convoys, the inevitable talk began. If the commanders were issuing more grenades, it meant they expected a close-up fight. Adams felt it as well as his men. No one wanted to charge yet another machine-gun nest. No matter how much Adams had grown to hate Germans, the thought of hand-to-hand fighting opened up that cold hole in his gut. If I have to kill them, he thought, I’d rather not look ’em in the eye. Not anymore. It’d be awfully nice if that Hitler bastard would just up and quit.

His own platoon stretched out behind him, no one talking, the men conserving their energy for the terrain. Scofield’s briefing had offered few details beyond the description of their ultimate goal, La Haye-du-Puits. But before they reached the village, there would be a sizable hill, what the maps called Hill 131, where the enemy would certainly be dug in. Beyond that was La Poterie Ridge and then Hill 95, the final obstacle before the village itself. Adams had no idea of a timetable, if anyone above Scofield had even guessed how long the mission was supposed to take, or just how many enemy troops were waiting for them. It was obvious to the paratroopers that someone far above them had decided that if the fight was likely to be a tough one, the airborne should throw the first punch.

He marched in a daze, fighting to stay alert, an essential with woods close on both sides of them. It was more than sleeplessness, or the weariness of too many marches. Adams had felt the numbness growing for days now, even before the death of Marley. It angered him, quiet fury in his brain he couldn’t sweep away. The men around him rarely talked about anything like this, seemed to go about their routine in the camps with matter-of-fact acceptance. Even Unger was still annoyingly chipper, the boy who had learned to become such an utterly efficient killer. Corporal Nusbaum still did his job with the same uninterested effort, always a hint that he would rather be doing anything else, probably outside the army. Adams assumed that before much longer Nusbaum would make sergeant, the regiment’s need to fill the gaps left by the cost of so many hard-fought engagements.

There were hints, often from Scofield, that Adams himself would be promoted, a field commission to second lieutenant. There was nothing appealing to Adams about a lieutenant’s bars, even with the raise in pay. I’m already the first one in line, he thought. They already do what I tell them to do, and as long as I’m a sergeant I can kick asses without getting court-martialed. It was a tired theme now: the training, jump school, curses, and screaming, what every instructor inflicted upon his men. He thought of Fort Benning, the jump towers, the first rides in the C-47s, terrified men, some who wouldn’t jump at all, men who couldn’t handle the training and would disappear without fanfare. How long ago, two years? His brain wouldn’t do the math, so he tried to bring himself back to the march, the woods, the men in front of him stepping slowly through the mud. Didn’t much matter how much ass I kicked at Benning, he thought. No matter what the army told me, I couldn’t make paratroopers out of men who weren’t designed for it. I sure as hell couldn’t make heroes. You can never predict that, no one can, not even Gavin. Unger…I figured the first time he heard machine-gun fire, he’d crawl under some rock and cry his eyes out. Now I know damned well he’s got my back, a kid! But he’ll never make sergeant. He’s too clean-cut, won’t say a single cussword. Never even heard him raise his voice. His mama’d be proud. What would my mama say? The cussing wouldn’t bother her. Wasn’t a day gone by that my old man didn’t spew out some kind of filth, most of it at her. Bastard. He still thinks soldiers are scum, the bottom of the ladder. What are you, old man? You dig holes in the ground. Try

this

for a couple days.

He fought it, the same anger that came to him at night, breaking his sleep. With the exhaustion of so many days in combat, his brain had no power to resist, so the sleep was never complete and never enough. I need to write her, he thought. I need to know if Clay’s all right, what the hell he’s doing in the Pacific. He won’t tell her of course, even if he could. Hope like hell he’s alive. That’s the main thing. Probably ought to tell her I’m alive too.

He stepped in a hole, jarred, mud up to his knee, sharp pain in his ankle. “Dammit!”

In front of him, faces turned back, and one man was up beside him quickly, a hand under his arm: Unger.

“You okay, Sarge? Gotta watch those holes. You’ll bust an ankle.”

“Get your ass back in line, Private. I need a medic, I’ll holler for one.”

Unger said nothing, just backed away, and Adams felt a strange sensation: guilt. He wanted to say something, an apology, but he stared ahead, glanced into the trees, thought, You’re getting too damned soft. Don’t do that. We’re not a damned social club. That idiot Marley did something to you. You better damn well forget about him. Buford too. Hell, I don’t even remember what they looked like.

But one part of his brain opened up, exposing the lie, and he saw Marley now, the horrible image of the missing leg, the man’s awful words:

Shoot me.

No! You son of a bitch. You had no right to say that to me. Show some guts! He stared down at his feet, slow footsteps in the mud, the pain in his ankle not as bad. I can’t keep thinking about this stuff. This job oughta get easier: every day, every damned fight, every time I fire this damned submachine gun. I’ve never lost my nerve, never thought what it’d be like to get hammered, cut up by shrapnel. You dwell on that stuff, you’ll end up hiding under a rock. Maybe I just need a few weeks’ rest. Some of these morons talk about how they’d love a nice little wound, like that’s all they’d need to get them home. Ask Marley about that.

He forced himself to watch the trees, pulled the Thompson off his shoulder, held it in his hands, flexed his back. He heard the rustles and clicks behind him, others doing the same, men who had learned to follow his lead. I guess if I did a bunny hop, they’d do that too. That’s what happens when they get tired of hearing you cuss them out. They start paying attention.

There were sounds in front of him, the chatter of a machine gun, men moving into the woods on either side of the road. Adams was alert again, energized, motioned to his men, called out, “Cover!”

He stumbled into the brush, his foot stabbing a hole, cold water over his boots. He pushed farther into the cover, knelt, listened over the sound of the men behind him, the firing scattered, nothing in the air above their heads. There were voices on the road now: Scofield.

Adams looked at the dirty faces watching him and said, “Stay put. Let me see what the hell’s going on.”

He realized he had been the first one in his platoon to hit the cover of the woods and was annoyed with himself. Dammit, you command these guys. You shouldn’t be the first one to take cover. Grab hold of it, Sergeant. He saw Scofield, talking into a radio, saw one of the lieutenants moving up the road quickly, a hand clamped down on his helmet.

Scofield waited for them both to move close, then said in a low voice, “We ran into an outpost of some kind. They didn’t put up much of a fight. We grabbed a few prisoners. Colonel Ekman says, No slowing down. Drive hard, straight ahead. They don’t seem to know we’re coming. Hill 131 is right there.”

Adams saw now: steeper ground to one side of the road. He looked at the lieutenant, who stared at the incline.

“I guess we climb,” Adams said.

“Right now, Sergeant.”

Adams moved to the edge of the woods, waved his men out, waited for them to gather. Unger moved up close.

“Where they at, Sarge?”

“Shut up. You see that hill? They’re waiting for us on top. They’re not coming down here, so we have to go up and get ’em.” He looked around, saw Scofield on the radio again. The captain caught the look, nodded, pointed toward the woods across the road. It was time to climb.

T

hey moved quickly, the fire from the German machine guns mostly ineffective, much of it passing over their heads. The rain had begun again, softening the sounds, and Adams led his men up through grass and rocks, natural cover, stopped behind a flat rock, his head down, raised up quickly, then down again. There was no response from above, no firing, and he thought, I’m not giving you a damned target, you Kraut sons of bitches. There was low brush scattered across the hill above him, dips and valleys, hiding places, and he heard voices, German, yards above him: urgent orders. The flat rock was a foot above his helmet, and he used the cover, looked back behind him, saw Unger behind another rock, watching him, the M-1 cradled close to Unger’s chest. All along the hillside, his men seemed glued in place, motionless, some behind fallen trees, some in the rocks, no sounds above the hiss of the rain. Higher up the hill, the voices came again. Adams wanted to peer up, but the men were moving down the hill, closer, and he froze. The first voice was an officer, certainly. Okay, so the Kraut told his men to move down to a better position. Mistake, pal.