The Story of the Greeks (Yesterday's Classics) (15 page)

The Persians were so delighted at having attained their purpose, and reduced the proud city to ashes, that they sent messengers to bear the glad tidings to the Persian capital. Here the people became almost wild with joy, and the whole city rang with their cries of triumph for many a day.

As you will remember, Themistocles had allowed the Spartans to command both the army and the navy. It was therefore a Spartan king, Eurybiades, who was head of the fleet at Salamis. He was a careful man, and was not at all in favor of attacking the Persians.

Themistocles, on the contrary, felt sure that an immediate attack, being unexpected, would prove successful, and therefore loudly insisted upon it. His persistency in urging it finally made Eurybiades so angry that he exclaimed, "Those who begin the race before the signal is given are publicly scourged!"

Themistocles, however, would not allow even this remark to annoy him, and calmly answered, "Very true, but laggards never win a crown!" The reply, which Eurybiades thought was meant for an insult, so enraged him that he raised his staff to strike the bold speaker. At this, the brave Athenian neither drew back nor flew into a passion: he only cried, "Strike if you will, but hear me!"

Once more Themistocles explained his reasons for urging an immediate attack; and his plans were so good, that Eurybiades, who could but admire his courage, finally yielded, and gave orders to prepare for battle."

The Battles of Salamis and Platæa

T

HE

fleets soon came face to face; and Xerxes took up his post on a mountain, where he sat in state upon a hastily built throne to see his vessels destroy the enemy. He had made very clever plans, and, as his fleet was far larger than that of the Greeks, he had no doubt that he would succeed in defeating them.

His plans, however, had been found out by Aristides, who was in the Island of Ægina; and this noble man rowed over to the fleet, at the risk of being caught by the enemy, to warn his fellow-citizens of their danger.

He first spoke to Themistocles, saying, "Rivals we have always been; let us now set all other rivalry aside, and only strive which can best serve his native country."

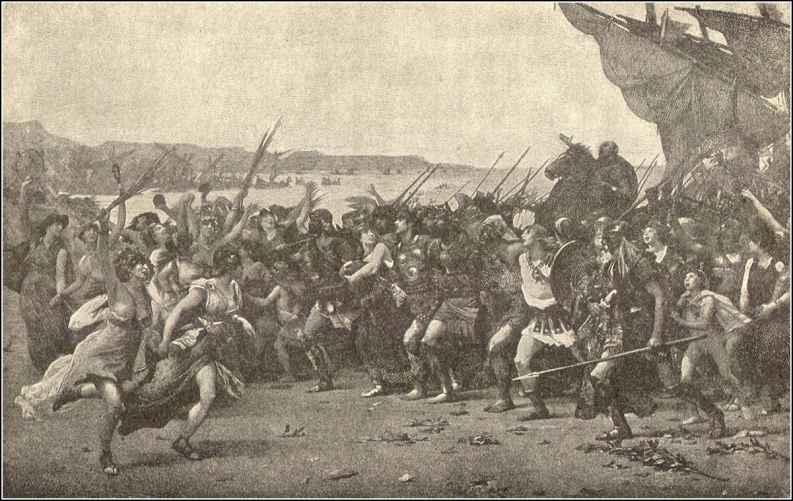

Themistocles agreed to this proposal, and managed affairs so wisely and bravely that the Greeks won a great victory. When they came home in triumph with much spoil, the women received them with cries of joy, and strewed flowers under their feet.

Return of the Victorious Greeks

From his high position, Xerxes saw his fleet cut to pieces; and he was so discouraged by this check, that he hastened back to Persia, leaving his brother-in-law Mardonius with an army of three hundred thousand men to finish the conquest of Greece.

The Greeks were so happy over their naval victory at Salamis, that they all flew to arms once more; and Pausanias, the Spartan king, the successor of Leonidas, was soon able to lead a large army against Mardonius.

The two forces met at Platæa, and again the Greeks won, although fighting against foes who greatly outnumbered them. Strange to relate, while Pausanias was winning one battle at Platæa, the other Spartan king, Eurybiades, defeated a new Persian fleet at Mycale.

These two victories finished the rout of the greatest army ever seen. Mardonius fled with the remnant of his host, leaving his tents, baggage, and slaves to the Greeks, who thus got much booty.

We are told that the Spartans, entering the Persian camp, were greatly amazed at the luxury of the tents. Pausanias stopped in the one that had been occupied by Mardonius, and bade the slaves prepare a meal such as they had been wont to lay before their master.

Then, calling his own Helots, he gave orders for his usual supper. When both meals were ready, they made the greatest contrast. The Persian tent was all decked with costly hangings, the table was spread with many kinds of rich food served in dishes of solid gold, and soft couches were spread for the guests.

The Spartan supper, on the contrary, was of the plainest description, and was served in ordinary earthenware. Pausanias called his officers and men, and, after pointing out the difference between the Spartan and the Persian style of living, he showed how much he liked plain food by eating his usual supper.

To reward Pausanias for his bravery and for defeating the enemy, the Greeks gave him a part of all that was best in the spoil. Next they set aside one tenth of it for Apollo, and sent it to his priest at Delphi as a token of gratitude for the favor of the god.

To show that they were grateful also to Zeus and Poseidon,—the gods who, they thought, had helped them to win their battles by land and by sea,—they sent statues to Olympia and Corinth; and they erected a temple in honor of Athene, the goddess of defensive war, on the battlefield of Platæa.

The Rebuilding of Athens

T

HE

Persians had been driven out of Greece, and the war with them was now carried on in Asia Minor instead of nearer home. The Greek army won many battles here also, and even managed to free the city of Miletus from the Persian yoke.

These triumphs encouraged all the Ionian cities, and they soon formed a league with the other Greeks, promising to help them against the Persians should the war ever be renewed. As soon as this alliance was made, the Greek fleet returned home, bringing back to Athens as a trophy the chains with which Xerxes had pretended to bind the rebellious sea.

In the mean while the Athenians, who had taken refuge on the Peloponnesus, had returned to their native city, where, alas! they found their houses and temples in ruins. The desolation was great; yet the people were so thankful to return, that they prepared to rebuild the town.

They were greatly encouraged in this purpose by an event which seemed to them a good omen. Near the temple of the patron goddess of Athens stood a sacred olive tree, supposed to have been created by her at the time when the city received her name.

This place had been burned by the invaders, and the returning Athenians sorrowfully gazed upon the blackened trunk of the sacred tree. Imagine their delight, therefore, when a new shoot suddenly sprang up from the ashes, and put forth leaves with marvelous speed.

The people all cried that the goddess had sent them this sign of her continued favor to encourage them to rebuild the city, and they worked with such energy that they were soon provided with new homes.

As soon as the Athenians had secured shelter for their families they began to restore the mighty walls which had been the pride of their city. When the Spartans heard of this, they jealously objected, for they were afraid that Athens would become more powerful than Sparta.

Of course, they did not want to own that they were influenced by so mean a feeling as jealousy, so they tried to find a pretext to hinder the work. This was soon found, and Spartan messengers came and told the Athenians that they should not fortify the town, lest it should fall again into the hands of the enemy, and serve them as a stronghold.

Themistocles suspected the real cause of these objections, and made up his mind to use all his talents to help his fellow-citizens. He therefore secretly assembled the most able men, and told them to go on with the work as fast as possible, while he went to Sparta to talk over the matter with the Lacedæmonians.

When he arrived at Sparta, he artfully prolonged the discussions until the walls were built high enough to be defended. Of course, there was now nothing to be done; but the Spartans were very angry, and waited anxiously for an opportunity to punish the Athenians. This came after a time, as you will see in the following chapters.

Death of Pausanias

P

AUSANIAS

,

the Spartan king, was very proud of the great victory he had won over the Persians at Platæa, and of the praise and booty he had received. He was so proud of it, that he soon became unbearable, and even wanted to become ruler of all Greece.

Although he had at first pretended to despise the luxury which he had seen in the tent of Mardonius, he soon began to put on the Persian dress and to copy their manners, and demanded much homage from his subjects. This greatly displeased the simple Greeks, and he soon saw that they would not help him to become sole king.

In his ambition to rule alone, he entirely forgot all that was right, and, turning traitor, secretly offered to help the Persians if they would promise to make him king over all Greece.

This base plot was found out by the ephors, the officers whose duty it was to watch the kings, and they ordered his own guards to seize him. Before this order could be carried out, however, Pausanias fled, and took refuge in a neighboring temple, where, of course, no one could lay violent hands upon him.

As the ephors feared he might even yet escape to Persia, and carry out his wicked plans, they ordered that the doors and windows of the temple should all be walled up.

It is said that as soon as this command had been given, Pausanias' mother brought the first stone, saying she preferred that her son should die, rather than live to be a traitor.

Thus walled in, Pausanias slowly starved to death, and the barriers were torn down only just in time to allow him to be carried out, and breathe his last in the open air. The Spartans would not let him die in the temple, because they thought his dying breath would offend the gods.

As Themistocles had been a great friend of Pausanias, he was accused of sharing his plans. The Athenians therefore rose up against him in anger, ostracized him, and drove him out of the country to end his life in exile.

After wandering aimlessly about for some time, Themistocles finally went to the court of Artaxerxes, the son and successor of Xerxes.

The Persian monarch, we are told, welcomed him warmly, gave him a Persian wife, and set aside three cities to supply him with bread, meat, and wine. Themistocles soon grew very rich, and lived on the fat of the land; and a traveler said that he once exclaimed, "How much we should have lost, my children and I, had we not been ruined by the Athenians!"

Artaxerxes, having thus provided for all Themistocles' wants, and helped him to pile up riches, fancied that his gratitude would lead him to perform any service the king might ask. He therefore sent for Themistocles one day, and bade him lead a Persian army against the Greeks.

But, although Themistocles had been exiled from his country, he had not fallen low enough to turn traitor. He proudly refused to fight; and it is said that he preferred to commit suicide, rather than injure the people he had once loved so dearly.

Cimon Improves Athens

A

S

soon as Themistocles had been banished from Athens, Aristides again became the chief man of the city, and he was also made the head and leader of the allies. He was so upright and just that all were ready to honor and obey him, and they gladly let him take charge of the money of the state.

In reward for his services, the Athenians offered him a large salary and many rich gifts; but he refused them all, saying that he needed nothing, and could afford to serve his country without pay.

He therefore went on seeing to all the public affairs until his death, when it was found that he was so poor that there was not enough money left to pay for his funeral. The Athenians, touched by his virtues, gave him a public burial, held his name in great honor, and often regretted that they had once been so ungrateful as to banish their greatest citizen, Aristides the Just.

As Aristides had watched carefully over the money of the allied states, and had ruled the Athenians very wisely, it is no wonder that Athens had little by little risen above Sparta, which had occupied the first place ever since the battle of Thermopylæ.

The Athenians, as long as Aristides lived, showed themselves just and liberal; but as soon as he was dead, they began to treat their former allies unkindly. The money which all the Greek states furnished was now no longer used to strengthen the army and navy, as first agreed, but was lavishly spent to beautify the city.

Now, while it was a good thing to make their town as fine as possible, it was certainly wrong to use the money of others for this purpose, and the Athenians were soon punished for their dishonesty.

Cimon, the son of Miltiades, was made the head of the army, and won several victories over the Persians in Asia Minor. When he returned to Athens, he brought back a great deal of spoil, and generously gave up all his share to improve the city and strengthen the walls.

It is said that Cimon also enlarged the beautiful gardens of the Academy; and the citizens, by wandering up and down the shady walks, showed that they liked this as well as the Lyceum, which, you will remember Pisistratus had given them.

They also went in crowds to these gardens to hear the philosophers, who taught in the cool porticoes or stone piazzas built all around them, and there they learned many good things.