The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (13 page)

The war was ended, and the army returned to Rome, where a magnificent triumph was awarded to the victorious consul. In the procession there were four of the fighting elephants which the Romans had captured, and all the people gazed in awe and wonder at the huge creatures, which they then saw for the first time.

Ancient Ships

T

HE

ships in olden times were very different from many of those which you see now. They were not made to go by steam, but only by sails or by oars. As sails were useless unless the wind happened to blow in a favorable direction, the people preferred to use oars, as a rule.

Even large ships were rowed from one place to another by well-trained slaves, who sat on benches along either side of the vessel, and plied their oars slow or fast according to the orders of the rowing master. These vessels with many rowers were called galleys. When the men sat on three tiers of benches, handling oars of different lengths, the boat they manned was known as a trireme.

There were other boats, with five, ten, or even twenty-four banks of oars; but for war the most useful were the triremes, or three-banked ships, and the quinqueremes, or those with five tiers of rowers. For battle, the ships were provided with metal points or beaks, and a vessel thus armed was rowed full force against the side of an enemy's ship to cut it in two.

Of all the people settled on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, the Carthaginians were now the best sailors. They dwelt at Carthage, in Africa, and, as their city was all the land they owned there at first, they soon turned all their energies to trading.

The Carthaginians thus amassed great wealth, and their city, which was near the present Tunis, and was twenty-three miles around, was one of the finest in the world.

In the course of their journeys, the Carthaginian sailors often visited Sicily, one of the most fertile countries in the world. Little by little they began to establish trading places there, and daily gained ground in the island. The Romans saw the advance of the Carthaginians with great displeasure; for it is but a step from Sicily to the Italian mainland, and they did not want so powerful a people for their neighbors.

The city of Syracuse was at this time the largest and strongest on the island, although the Carthaginians had waged many wars against it. There was also another city that was independent, which was occupied by a band of soldiers called Mamertines. A quarrel between these two cities led to war, and the Mamertines were so badly defeated that they asked the Romans for help.

When Hiero, the King of Syracuse, heard that Rome was planning to help his enemies, he sought aid from Carthage, and began to get ready for the coming war. The Romans, however, boldly crossed over into Sicily, and won such great victories that Hiero soon made peace with them, and he remained friendly to Rome as long as he lived.

The Carthaginians were thus left to carry on the war without the help of Syracuse. Now while the Roman legions were noted for their bravery on land, the Romans soon realized that Carthage would have the advantage, because it had so many ships.

A navy was needed to carry on the war with any hopes of success, and as the Romans had no vessels of war, they began right away to build some. A Carthaginian quinquereme, wrecked on their shores, was used as a model. While the shipbuilders were making the one hundred and twenty galleys which were to compose the fleet, the future captains trained their crews of rowers by daily exercise on shore.

Such was the energy of the Romans that in the short space of two months the fleet was ready. As the Romans were more experienced in hand-to-hand fighting than any other mode of warfare, each ship was furnished with grappling hooks, which would serve to hold the attacked vessel fast, and would permit the Roman soldiers to board it and kill the crew.

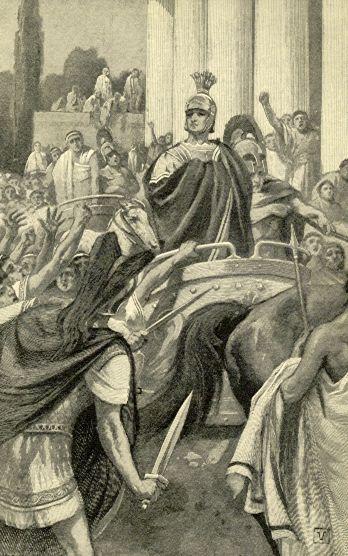

The fleet was placed under the command of Duilius Nepos, who met the Carthaginian vessels near Mylæ, on the coast of Sicily, and defeated them completely. Most of the enemy's ships were taken or sunk, and, when Duilius returned to Rome, the senate awarded him the first naval triumph.

In the procession, the conqueror was followed by his sailors, bearing the bronze beaks of the Carthaginian galleys which they had taken. These beaks, called "rostra," were afterwards placed on a column in the Forum, near the orators' stand, which was itself known as the Rostra, because it was already adorned by similar beaks of ships.

Duilius was further honored by an escort of flute players and torchbearers, who accompanied him home from every banquet he attended. As no one else could boast of such an escort, this was considered a great privilege.

Regulus and the Snake

T

HE

war against Carthage lasted many years, with sundry interruptions. The Carthaginians made many promises to the Romans, but broke them so often that "Punic faith" (that is, Carthaginian faith) came to mean the same as treachery or deceit.

When both parties were weary of the long struggle, the Romans resolved to end it by carrying the war into Africa. An army was therefore sent out under the command of Regulus. The men landed in Africa, where a new and terrible experience awaited them.

One day, shortly after their arrival, the camp was thrown into a panic by the appearance of one of the monster snakes for which Africa is noted, but which the Romans had never seen. The men fled in terror, and the serpent might have routed the whole army, had it not been for their leader's presence of mind.

Instead of fleeing with the rest, Regulus bravely stood his ground, and called to his men to bring one of the heavy machines with which they intended to throw stones into Carthage. He saw at once that with a ballista, or catapult, as these machines were called, they could stone the snake to death without much risk to themselves.

Story of Regulus

Reassured by his words and example, the men obeyed, and went to work with such good will that the snake was soon slain. Its skin was kept as a trophy of this adventure, and sent to Rome, where the people gazed upon it in wonder; for we are told that the monster was one hundred and twenty feet long. Judging by this account, the "snake story" is very old indeed, and the Romans evidently knew how to exaggerate.

Having disposed of the snake, the Roman army now proceeded to war against the Carthaginians. These had the larger army, and many fighting elephants; so the Romans were at last completely defeated, and Regulus was made prisoner, and taken into Carthage in irons.

The Carthaginians had won this great victory under a Greek general named Xanthippus to whom, of course, the people were very grateful; but it is said that they forgot his services, and ended by drowning him.

The rulers of Carthage soon had cause to regret the loss of Xanthippus; for the Romans, having raised a new army, won several victories in Sicily, and drove the Carthaginian commander, Hasdrubal, out of the island.

As you have already seen, the people in those days rewarded their generals when successful; but when a battle was lost, they were apt to consider the general as a criminal, and to punish him for being unlucky, by disgrace or death. So when Hasdrubal returned to Carthage defeated, the people all felt indignant, and condemned him to die.

Then the Carthaginians, weary of a war which had already lasted about fifteen years, sent an embassy to Rome to propose peace; but their offers were refused. About this time Regulus was killed in Carthage, and in later times the Romans told a story of him which you will often hear.

They said that the Carthaginians sent Regulus along with the embassy, after making him promise to come back to Carthage if peace were not declared. They did this thinking that, in order to secure his freedom, he would advise the Romans to stop the war.

Regulus, however, was too good a patriot to seek his own welfare in preference to that of his country. When asked his advice by the Roman senate, he bade them continue the fight, and then, although they tried to detain him in Rome, he insisted upon keeping his promise and returning to captivity.

When he arrived in Carthage with the embassy, and it became known that he had advised the continuation of the war, the people were furious, and put him to death with frightful tortures.

The war went on for seven or eight years more, until even the Romans longed for peace. A truce was then made between Rome and Carthage, which put an end to the greatest war the Romans had yet waged,—the struggle which is known in history as the First Punic War.

Hannibal Crosses the Alps

T

HE

peace won thus after years of fighting was very welcome, and the Romans gladly closed the Temple of Janus, for the first time since the days of Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome.

As there was no fighting to be done anywhere, the people now began to cultivate the arts of peace. For the first time in their busy lives, they took a deep interest in poetry, and enjoyed satires, tragedies, and comedies. But while the first style of poetry was an invention of their own, they borrowed the others from the Greeks.

As they knew that an inactive life would not please them long, they made sundry improvements in their arms and defenses, and prepared for future wars. Then, to prevent their weapons from rusting, they joined the Achæans in making war against the pirates who infested the Adriatic Sea.

Soon after this, the Gauls again invaded Italy, and came down into Etruria, within three days' march of Rome. The citizens flew to arms to check their advance, and defeated them in a pitched battle. Forty thousand of the barbarians were killed, and ten thousand were made prisoners.

In a second encounter, the King of the Gauls was slain, and the people bought peace from the victorious Romans by giving up to them all the land which they occupied in the northern part of Italy.

While Rome was thus busy making many conquests, the Carthaginians had not been idle either. In a very short time their trade was as brisk as ever, and they conquered about half of Spain. Then as soon as they earned enough money, and finished their preparations, they broke the treaty they had made with Rome, by besieging Saguntum, a Spanish city under the protection of the Romans.

The Roman senate sent an ambassador to Carthage to complain of this breach of the treaty, and to ask that the general who had taken Saguntum should be given up to them. This general was Hannibal, a man who hated the Romans even more than he loved his own country. When only a little boy, he had taken a solemn oath upon the altar of one of the Carthaginian gods, that he would fight Rome as long as he lived.

Hannibal was a born leader, and his dignity, endurance, and presence of mind made him one of the most famous generals of ancient times. The Carthaginians had not yet had much chance to try his skill, but they were not at all ready to give him up. When the Roman ambassador, Fabius, saw this, he strode into their assembly with his robe drawn together, as if it concealed some hidden object.

"Here I bring you peace or war!" he said. "Choose!" The Carthaginians, nothing daunted by his proud bearing, coolly answered: "Choose yourself!"

"Then it is war!" replied Fabius, and he at once turned away and went back to Rome to make known the result of his mission.

Hannibal, in the mean while, continued the war in Spain, and when he had forced his way to the north of the country, he led his army of more than fifty thousand men over the Pyrenees and across Gaul. His object was to enter Italy by the north, and carry on the war there instead of elsewhere. Although it was almost winter, and the huge barrier of the Alps rose before him, he urged his men onward.

The undertaking seemed impossible, and would never have been attempted by a less determined man. Thanks to Hannibal's coolness and energy, however, the army wound steadily upward along the precipices, and through the snow. Although over half the men perished from cold, or from the attacks of the hostile inhabitants, the remainder came at last to the Italian plains. It had taken a whole fortnight to cross the Alps.

The Romans Defeated

W

HEN

the Romans heard of Hannibal's approach, the consul Scipio advanced with an army to fight him, and the two forces met face to face near the river Ticinus. Here a battle took place, and Hannibal, reenforced by Gallic troops, won a brilliant victory.

A second battle was fought and won by stratagem at the river Trebia, where a frightful slaughter of the Romans took place. Beaten back twice, the Romans rallied again, only to meet with a still greater defeat on the shores of Lake Trasimenus. In their distress at the news of these repeated disasters, the Roman people gave the command of their army to Fabius, a man noted for his courage no less than for his caution.

Fabius soon perceived that the Romans were not able to conquer Hannibal in a pitched battle, and, instead of meeting him openly, he skirmished around him, cutting off his supplies, and hindering his advance. On one occasion, by seizing a mountain pass, Fabius even managed to hedge the Carthaginians in, and fancied that he could keep them prisoners and starve them into submission; but Hannibal soon made his escape. By his order, the oxen which went with the army to supply it with food, and to drag the baggage, were all gathered together. Torches were fastened securely to their horns; and then lighted. Blinded and terrified, the oxen stampeded, and rushed right through the Roman troops, who were forced to give way so as not to be crushed to death. The Carthaginians then cleverly took advantage of the confusion and darkness to make their way out of their dangerous position, and thus escaped in safety.