The Story of the Romans (Yesterday's Classics) (3 page)

At these words Æneas sprang to his feet, and cried that the prophecy was fulfilled at last, and that now they could settle in the beautiful country they had reached. The next day they were welcomed by Latinus, King of Latium, who, after hearing their story, remembered his dream, and promised that Æneas should have his daughter Lavinia in marriage.

The Wolf and the Twins

A

LTHOUGH

Æneas had been so kindly welcomed to Latium by the king, his troubles were not yet ended. Turnus, the young king who had been engaged to Lavinia, was angry at her being given to another, and, in the hope of winning her still, he declared war against the Trojan strangers.

During the war Æneas and Turnus both won much glory by their courage. At last they met in single combat, in which Turnus was conquered and slain; and Æneas, having thus got rid of his rival, married the fair princess.

He then settled in Latium, where he built a city which was called Lavinium, in honor of his wife. Some time after, Æneas fell in battle and was succeeded by his sons. The Trojans and Latins were now united, and during the next four hundred years the descendants of Æneas continued to rule over them; for this was the kingdom which the gods had promised him when he fled from Troy.

The throne of Latium finally came to Numitor, a good and wise monarch. He had a son and a daughter, and little suspected that any one would harm either of them.

Unfortunately for him, however, his brother Amulius was anxious to secure the throne. He took advantage of Numitor's confidence, and, having driven his brother away, killed his nephew, and forced his niece, Rhea Sylvia, to become a servant of the goddess Vesta.

The girls who served this goddess were called Vestal Virgins. They were obliged to remain in her temple for thirty years, and were not allowed to marry until their time of service was ended. They watched over a sacred fire in the temple, to prevent its ever going out, because such an event was expected to bring misfortune upon the people.

If any Vestal Virgin proved careless, and allowed the sacred fire to go out, or if she failed to keep her vow to remain single, she was punished by being buried alive. With such a terrible fate in view, you can easily understand that the girls were very obedient, and Amulius thought that there was no danger of his niece's marrying as long as she served Vesta.

A Vestal Virgin

We are told, however, that Mars, the god of war, once came down upon earth. He saw the lovely Rhea Sylvia, fell in love with her, wooed her secretly, and finally persuaded her to marry him without telling any one about it.

For some time all went well, and no one suspected that Rhea Sylvia, the Vestal Virgin, had married the god of war. But one day a messenger came to tell Amulius that his niece was the mother of twin sons.

The king flew into a passion at this news, and vainly tried to discover the name of Rhea Sylvia's husband. She refused to tell it, and Amulius gave orders that she should be buried alive. Her twin children, Romulus and Remus, were also condemned to die; but, instead of burying them alive with their mother, Amulius had them placed in their cradle, and set adrift on the Tiber River.

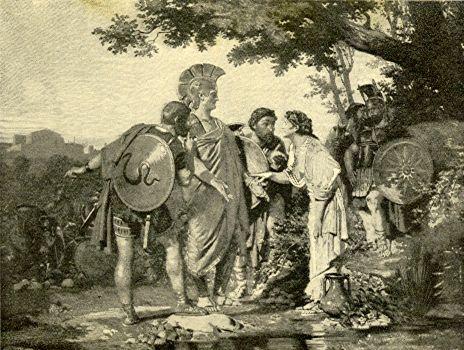

The king thought that the babes would float out to sea, where they would surely perish; but the cradle drifted ashore before it had gone far. There the cries of the hungry children were heard by a she-wolf. This poor beast had just lost her cubs, which a cruel hunter had killed. So instead of devouring the babies, the she-wolf suckled them as if they were the cubs she had lost; and the Romans used to tell their children that a woodpecker brought the twins fresh berries to eat.

Thus kept alive by the care of a wolf and a bird, the children remained on the edge of the river, until a shepherd passed that way. He heard a strange noise in a thicket, and, on going there to see what was the matter, found the children with the wolf. Of course the shepherd was greatly surprised at this sight; but he took pity on the poor babies, and carried them home to his wife, who brought them up.

Romulus Builds Rome

R

EMUS

and Romulus, the twins who had been nursed by the she-wolf, grew up among the shepherds. They were tall and strong, and so brave that all their companions were ready to follow them anywhere. One day, when they were watching their flocks on the hillside, their pasture was claimed by the shepherds who were working for Numitor.

The young men were angry at this, and as the shepherds would not go away, they began to fight. As they were only two against many, they were soon made prisoners, and were led before Numitor.

Their strong resemblance to the royal family roused the old man's suspicions. He began to question them, and soon the young men found out who they were. Then they called together a few of their bravest companions, and entered the city of Alba, where Amulius dwelt. The unjust king, taken by surprise, was easily killed; and the brothers made haste to place their grandfather, Numitor, again on the throne.

Remus and Romulus were too restless and fond of adventure to enjoy the quiet life at Alba, so they soon left their grandfather's court to found a kingdom of their own. They had decided that they would settle in the northern part of Latium, on the banks of the Tiber, in a place where seven hills rose above the surrounding plain. Here the two brothers said that they would build their future city.

Before beginning, however, they thought it would be well to give the city a name. Each wanted the honor of naming it, and each wanted to rule over it when it was built. As they were twins, neither was willing to give up to the other, and as they were both hot-tempered and obstinate, they soon began to quarrel.

Their companions then suggested that they should stand on separate hills the next day, and let the gods decide the question by a sign from the heavens. Remus, watching the sky carefully, suddenly cried that he saw six vultures. A moment later Romulus exclaimed that he could see twelve; so the naming of the city was awarded to him, and he said that it should be called Rome.

The next thing was to draw a furrow all around the hill chosen as the most favorable site. The name of this hill was the Palatine. Romulus, therefore, harnessed a bullock and a heifer together, and began to plow the place where the wall of the town was to be built. Remus, disappointed in his hopes of claiming the city, began to taunt his brother, and, in a fit of anger, Romulus killed him.

Although this was a horrible crime, Romulus felt no remorse, and went on building his capital. All the hot-headed and discontented men of the neighboring kingdoms soon joined him; and the new city, which was founded seven hundred and fifty-three years before Christ, thus became the home of lawless men.

The city of Rome was at first composed of a series of mud huts, and, as Romulus had been brought up among shepherds, he was quite satisfied with a palace thatched with rushes. As the number of his subjects increased, however, the town grew larger and richer, and before long it became a prosperous city, covering two hills instead of one. On the second hill the Romans built a fortress, or citadel, which was perched on top of great rocks, and was the safest place in case of an attack by an enemy.

This is the city of which you are going to read the story. You will learn in these pages how it grew in wealth and power until it finally became the most important place in the world, and won for itself the name of the Eternal City.

The Maidens Carried Off

A

S

all the robbers, murderers, and runaway slaves of the kingdoms near by had come to settle in Rome, there were soon plenty of men there. Only a few of them, however, had wives, so women were very scarce indeed. The Romans, anxious to secure wives, tried to coax the girls of the neighboring states to marry them; but as they had the reputation of being fierce and lawless, their wooing was all in vain.

Romulus knew that the men would soon leave him if they could not have wives, so he resolved to help them get by a trick what they could not secure by fair means. Sending out trumpeters into all the neighboring towns and villages, he invited the people to come to Rome and see the games which the Romans were going to celebrate in honor of one of their gods.

As these games were wrestling and boxing matches, horse and foot races, and many other tests of strength and skill, all the people were anxious to see them; so they came to Rome in crowds, unarmed and in holiday attire. Whole families came to see the fun, and among the spectators were many of the young women whom the Romans wanted for wives.

Romulus waited until the games were well under way. Then he suddenly gave a signal, and all the young Romans caught up the girls in their arms and carried them off to the houses, in spite of their cries and struggles.

The fathers, brothers, and lovers of the captive maidens would gladly have defended them; but they had come to the games unarmed, and could not strike a blow. As the Romans refused to give up the girls, they rushed home for their weapons, but when they came back, the gates of Rome were closed.

While these men were raging outside the city, the captive maidens had been forced to marry their captors, who now vowed that no one should rob them of their newly won wives, and prepared to resist every attack. Most of the women that had been thus won came from some Sabine villages; and the Romans had easy work to conquer all their enemies until they were called upon to fight the Sabines. The war with them lasted a long time, for neither side was much stronger than the other.

At last, in the third year, the Sabines secured an entrance to the citadel by bribing Tarpeia, the daughter of the gate keeper. This girl was so vain, and so fond of ornaments, that she would have done anything to get some. She therefore promised to open the gates, and let the Sabine warriors enter during the night, if each of them would give her what he wore on his left arm, meaning a broad armlet of gold.

The Sabines promised to give her all she asked, and Tarpeia opened the gates. As the warriors filed past her, she claimed her reward; and each man, scorning her for her meanness, flung the heavy bronze buckler, which he also wore on his left arm, straight at her.

Tarpeia

Tarpeia sank to the ground at the first blow, and was crushed to death under the weight of the heavy shields. She fell at the foot of a steep rock, or cliff, which has ever since been known as the Tarpeian Rock. From the top of this cliff, the Romans used to hurl their criminals, so that they might be killed by the fall. In this way many other persons came to die on the spot where the faithless girl had once stood, when she offered to sell the city to the enemy for the sake of a few trinkets.

Union of Sabines and Romans

T

HE

Sabine army had taken the citadel, thanks to Tarpeia's vanity; and on the next day there was a desperate fight between them and the Romans who lived on the Palatine hill. First the Romans and then the Sabines were beaten back; and finally both sides paused to rest.

The battle was about to begin again, and the two armies were only a few feet apart, threatening each other with raised weapons and fiery glances, when all at once the women rushed out of their houses, and flung themselves between the warriors.

In frantic terror for the lives of their husbands on one side, and of their fathers and brothers on the other, they wildly besought them not to fight. Those who had little children held them up between the lines of soldiers, and the sight of these innocent babes disarmed the rage of both parties.

Instead of fighting any more, therefore, the Romans and Sabines agreed to lay down their arms and to become friends. A treaty was made, whereby the Sabines were invited to come and live in Rome, and Romulus even agreed to share his throne with their king, Tatius.

Thus the two rival nations became one, and when Tatius died, the Sabines were quite willing to obey Romulus, who was, at first, an excellent king, and made many wise laws.

As it was too great a task for him to govern the unruly people alone, Romulus soon formed an assembly of the oldest and most respected men, to whom he gave the name of senators. They were at first the advisers of the king; but in later times they had the right to make laws for the good of the people, and to see that these laws were obeyed.