The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam (26 page)

Read The Sultan and the Queen: The Untold Story of Elizabeth and Islam Online

Authors: Jerry Brotton

Tags: #History, #Middle East, #Turkey & Ottoman Empire, #Europe, #Great Britain, #Renaissance

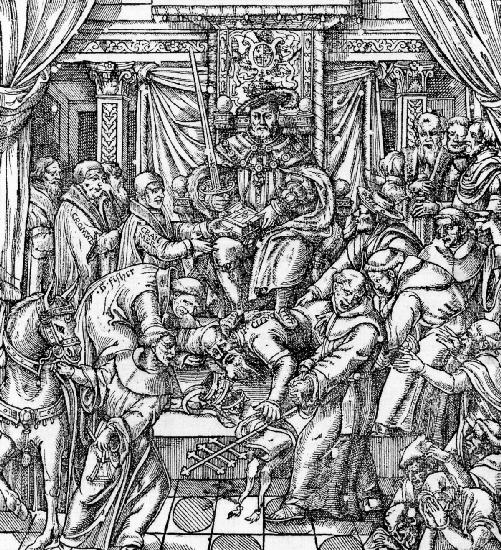

Henry VIII using Pope Clement VII as a footstool in John Foxe’s

Acts and Monuments

(1583).

Perhaps Greene was right that Tamburlaine and his creator were both atheists. In Part Two, Tamburlaine spends much of his time taunting any and all deities, including the Prophet Muhammad. Marlowe shows extensive knowledge of recent reports about Islamic theology. Indeed, his mention of the “Zoacum” tree in Act II, scene 3, suggests that he may even have read the Qur’an, where the tree is mentioned in surah 37.

13

In the opening scenes of Part Two, Tamburlaine’s lieutenant Orcanes signs a peace treaty with Sigismund, King of Hungary, promising:

By sacred Mahomet, the friend of God,

Whose holy Alcoran remains with us,

Whose glorious body, when he left the world,

Clos’d in a coffin mounted up the air,

And hung on stately Mecca’s temple roof,

I swear to keep this truce inviolable.

14

Tamburlaine himself proves less respectful. Much later in the play, after he captures Babylon and orders the slaughter of its inhabitants, he asks Usumcasane, King of Morocco:

where’s the Turkish Alcoran,

And all the heaps of superstitious books

Found in the temples of that Mahomet

Whom I have thought a god? They shall be burned.

15

Boasting that “I live untouch’d by Mahomet,” Tamburlaine then taunts the Prophet, calling out as he watches the Qur’an burn:

Now, Mahomet, if thou have any power,

Come down thyself and work a miracle.

Thou art not worthy to be worshippèd

That suffers flames of fire to burn the writ

Wherein the sum of thy religion rests.

16

Continuing his diatribe, he asks:

Why send’st thou not a furious whirlwind down

To blow thy Alcoran up to thy throne

Where men report thou sitt’st by God himself,

Or vengeance on the head of Tamburlaine,

That shakes his sword against thy majesty

And spurns the abstracts of thy foolish laws?

17

He tells his soldiers that “Mahomet remains in hell,” unable to respond to such mockery, and they should “seek out another godhead to adore.”

18

Less than twenty lines later, Tamburlaine feels “distemper’d suddenly,” and two scenes later he is dead. Is it just coincidence or is Marlowe finally bringing down the wrath of God upon his antihero? As he enters the play’s final scene, Tamburlaine addresses his general Techelles and other close advisers and rails against all religions:

What daring God torments my body thus

And seeks to conquer mighty Tamburlaine?

Shall sickness prove me now to be a man,

That have been termed the terror of the world?

Techelles and the rest, come, take your swords,

And threaten him whose hand afflicts my soul.

Come, let us march against the powers of heaven

And set black streamers in the firmament

To signify the slaughter of the gods.

Ah, friends, what shall I do? I cannot stand.

Come, carry me to war against the gods,

That thus envy the health of Tamburlaine.

19

Marlowe makes it quite clear here that his hero is the scourge of

any

divinity, not just the God of Islam or Christianity. Here, finally and majestically, the body of the man and the mind of God collide: the “terror of the world” has a soul but he will die in “war against the gods.” Only God, Marlowe suggests, can defeat such a man.

Marlowe was fully aware of Elizabethan England’s close relations with the rulers of Persia, Morocco and the Ottoman Empire that people his play. While he was studying at Cambridge and writing

Tamburlaine,

he was already associating with the intelligence networks run by Burghley and Walsingham, and he might well have been privy to aspects of the ambiguous and conflicted policy of Elizabeth’s advisers toward the Islamic world.

20

Marlowe’s play had little interest in either celebrating or condemning the crown’s strategic alliances with Islam. It explored the contradictory and ambivalent emotions inspired by a traditional enemy that could be—and had been—quickly transformed into an ally, and possibly even a savior. The result was a new kind of drama that embraced duality and encouraged the audience to revel in both the horror and the delight of identifying with a charismatic outsider. The play created a shiver of pleasure rather than a somber moral lesson; it asked the audience to make up their own minds about its eastern hero and “applaud his fortunes as you please.” Judging by the “sundrie times” the play was “showed upon stages in the city of London,” his audience could not get enough of it.

21

Tamburlaine

’s success spawned a new generation of playwrights, eager to exploit Marlowe’s style and exotic settings. One of the first was Thomas Kyd, a close friend and former roommate who soon became embroiled in the murky world of Elizabethan espionage. Kyd would subsequently be arrested, tortured and imprisoned on charges of blasphemy arising from documents that he said in fact belonged to Marlowe. The two died within little more than a year of each other, Marlowe in May 1593, Kyd in August 1594. Kyd probably wrote his celebrated revenge play

The Spanish Tragedy

within months of

Tamburlaine

. The backdrop for Kyd’s violent and bloody drama was the political struggle between Spain and Portugal, a prescient issue in the late 1580s. It featured a play within the play dramatizing the Ottoman sultan Süleyman the Magnificent’s fictional pursuit of the Greek beauty Perseda.

The Spanish Tragedy

was so successful that in 1592 Kyd rushed out a follow-up,

Soliman and Perseda,

which focused exclusively on the Ottoman sultan’s invasion of Rhodes, his capture of Perseda and his eventual downfall.

Around the time of the Armada’s defeat, another of Marlowe’s contemporaries, George Peele, turned to an earlier moment of conflict involving Iberia for inspiration. If Bilqasim, the Moroccan ambassador, had seen Peele’s

Battle of Alcazar

on one of the many occasions it was performed by Lord Strange’s Men at the Rose Theatre in Bankside, he would have been perplexed to see his sovereign, Ahmad al-Mansur, renamed “Muly Mahamet Seth.” Peele took the innovative decision to dramatize a recent historical event, drawing on publications that described the battle. The result was more like war reportage than epic drama. It was the first play in English history to use a Presenter to introduce each act, and the first set exclusively in Morocco to put a Moor on the English stage. What Peele did with his “Moorish” characters would have a profound effect on subsequent Elizabethan drama.

Peele referred to the ruling sultan, Abd al-Malik I, as “Abdelmelec, also known as Muly Molocco, rightful King of Morocco.” His scheming nephew, the exiled Abu Abdallah, Peele called “Muly Mahamet, the Moor” (not to be confused with Muly Mahamet Seth). While Abdelmelec is represented as the legitimate “brave, Barbarian lord Muly Molocco,” Abu Abdallah is “the barbarous Moor, / The negro Muly Mahamet,” a “tyrant,” “Black in his look and bloody in his deeds.”

22

The term “Moor” was derived from the Greek word Mαῦρος, which had two distinct meanings: an inhabitant of Mauretania (the ancient land covering today’s Moroccan coast) and “dark” or “dim.” During the Middle Ages the Latin derivation “Maurus” took on an ethnographic sense and, following the Islamic conquest of North Africa, came to be used as a synonym for “Mahomet’s sect” (Muslims).

23

The word was thus an explosive mix of religion and ethnicity that Peele exploited to the full as he contrasted the two contenders for the Moroccan throne. He drew on contemporary sources to argue that Moors “are of two kinds, namely white or tawny Moors, and Negroes or black Moors.”

24

His face made up with burned cork and oil and wearing black gloves, the actor playing Muly Mahamet was easily transformed into the devilish, scheming “blackamoor,” while Abdelmelec was his complete antithesis, a virtuous “tawny Moor,” a suitable figure for English merchants to do business with.

The son of Peele’s Abdelmelec would inherit the kingdom and establish an alliance with Elizabeth. But this is where the play began to run into problems. Despite their apparent differences, both Abdelmelec and Muly Mahamet are acknowledged as Muslims and “descended from the line / Of Mahomet.”

25

Although Abdelmelec is seen as the legitimate ruler, he announces, “I do adore / The sacred name of Amurath the Great,”

26

the Ottoman sultan Murad III, with whom he was in league. Muly Mahamet, by contrast, allied himself with a Christian king, Sebastian I. From this point in the play onward, Peele has to work hard to portray Sebastian as a courageous but tragic figure, flawed by his Catholicism and therefore easily manipulated by the scheming Muly Mahamet.

The play’s anti-Catholic bias intensifies with the introduction of Thomas Stukeley, surrounded by Irish clergy and Italian soldiers, heading for Ireland and hoping to “restore it to the Roman faith.”

27

Sebastian persuades Stukeley to join his Moroccan crusade, but the bombastic Englishman’s thundering speeches reveal him to be a pale, opportunistic shadow of Tamburlaine:

There shall be no action pass my hand or my sword

That cannot make a step to gain a crown,

No word shall pass the office of my tongue

That sounds not of affection to a crown,

No thought have being in my lordly breast

That works not every way to win a crown.

Deeds, words and thoughts shall all be as a king’s,

My chiefest company shall be with kings,

And my deserts shall counterpoise a king’s.

Why should not I then look to be a king?

I am the Marquess now of Ireland made

And will be shortly King of Ireland.

King of a mole-hill had I rather be

Than the richest subject of a monarchy.

28

The vain and conceited Stukeley lacks the ambition and linguistic prowess of Tamburlaine. He is blandly fixated on the pursuit of a crown.

At the end of Peele’s play, his sources dictated that everyone should die. This duly happens in a climactic battle scene, in which Muly Mahamet demands: “A horse, a horse, villain, a horse,” prefiguring the demise of another tragic villain, Shakespeare’s Richard III, four years later. The only man left standing is Muly Mahamet Seth, Elizabeth’s future ally, but even he does little more than order the mutilation of Muly Mahamet’s body followed by a Christian burial for Sebastian (which did not happen historically). Like Marlowe’s

Tamburlaine,

there is no obvious lesson from Peele’s play. It ends with no Chorus to provide a simple moral and offers no character with which the audience can identify. One is left to choose between the pompous Abdelmelec, the pious Sebastian, the scheming Muly Mahamet and the mercenary Stukeley.

29

This lack of simple identifications was in part a reflection of the contradictory nature of England’s relations with the Muslim world in the late 1580s. These contradictions provided an alternative to the prescriptive histories of classical Rome and Greece, allowing Elizabethan dramatists to develop their own idiom, addressing their audiences’ hopes and fears by staging them in a faraway land where the horrors of warfare, murder, atheism and tyranny could be explored in relative safety, free from the suspicious eyes of censors. We might think the play recommends the avoidance of Catholic-Muslim conflicts, while counseling Elizabeth against pursuing an alliance with al-Mansur, but Tudor dramatists were not moralizing priests or foreign policy advisers. They wanted to exploit the ambivalent emotions created by English experiences in the east as spectacular, captivating drama.