The Surf Guru (19 page)

Authors: Doug Dorst

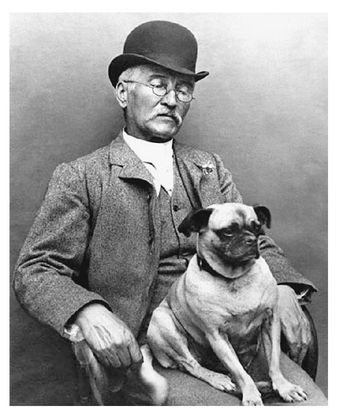

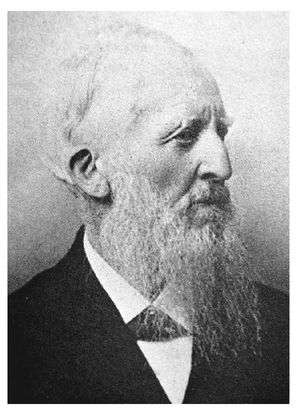

Aeneas Scottwell-Scott

I shall begin my series of profiles with a sketch of the botanist to whom all the backbiters, bullies, dullards, and thieves who rule our field ought to compare themselves, so they can see how glaring their deficits are.

Aeneas Scottwell-Scott did not care what others thought of his academic credentials or lack thereof. He did not care what others thought of his scientific conclusions, so confident was he in his species concept, his accurate observations and measurements, his encyclopaedic knowledge of botany and the history of its study. He did not care what others thought of his wardrobe or his failure to marry or his quickness to raise his fists. He did not care what others thought of his disinterest in politics, sport, or washing. He did not care what others thought of his approach to teaching, which was demanding, acerbic, and stern, and which occasionally made use of ear-boxing as a tool for emphasis.

Because he was an autodidact and an iconoclast, he was never embraced by the white-haired panjandra of east-coast botany.

15

These fops and frauds, in their towers of ivory (and ivy), were too busy listening to each other's clarion-blasts of flatus to hear the voice of a brilliant man in the wilderness, a man who routinely risked his physical and financial health trying to bring taxonomic order to the flora of the American West.

16

15

These fops and frauds, in their towers of ivory (and ivy), were too busy listening to each other's clarion-blasts of flatus to hear the voice of a brilliant man in the wilderness, a man who routinely risked his physical and financial health trying to bring taxonomic order to the flora of the American West.

16

Scottwell-Scott improved those of us who studied with him. He taught us to observe meticulously, to avoid the small but disastrous errors that issue from hasty or careless work, and to be upstanding, honest, and truthful in all mattersâ botanical, financial, personal, or any other. He was a father to meâto all of his students, I once thoughtâand if he occasionally withheld approval, validation, warmth, or rewards, he did so with our intellectual and personal maturation in mind. (He was not, for example, one of those people who use each opportunity to name a new species as currency for bestowing thanks, building egos, or begging for funds. He most certainly did not bestow such favors on us, his students, except in one instance (

Ptimorus kingsleei

). In the interests of history, I asked him on several occasions to explain this aberration. I suspect he did not recall, for his mind had dulled a bit with age and infirmity, and he was never forthcoming with a convincing answer.

17

In any event, he never bothered to petition the Society for renaming the offending

Ptimorus

, which is unsurprising; he was a man of fieldwork, not “paperwork.”)

Ptimorus kingsleei

). In the interests of history, I asked him on several occasions to explain this aberration. I suspect he did not recall, for his mind had dulled a bit with age and infirmity, and he was never forthcoming with a convincing answer.

17

In any event, he never bothered to petition the Society for renaming the offending

Ptimorus

, which is unsurprising; he was a man of fieldwork, not “paperwork.”)

Our field has suffered in recent years because Scottwell-Scott's lessons have fallen out of vogueâeven among some of his former protégés, such as the klepto- and ego-maniacal Kingslee and the spineless Fitzgilbert. I have maintained my mentor's high standards and, like him, I have suffered as a result. However, these brief biographies are not the proper venue for detailing my mistreatment by my “colleagues” and by Mulholland University, and thus I shall not do so herein.

Profile #19

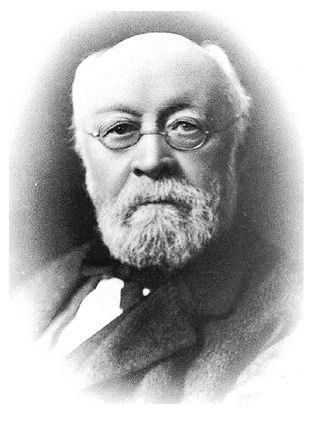

Clark Sydney Grimshaw

Word comes that Grimshaw has gone and died, although it is hard to fathom how anyone noticed. He had published no work of value for decades. We should be grateful, I suppose, for the prolonged moribundity of his career, as it leaves us with less of his willfully obtuse scholarship to undo.

18

Profile #6418

Colton Cates

How Cates escaped this life without being formally repudiated as the serial plagiarist he was

19

is one of the earth's great mysteries. I suspect a wide-ranging scheme of bribery and/ or intimidation.

19

is one of the earth's great mysteries. I suspect a wide-ranging scheme of bribery and/ or intimidation.

Of course, even his meager output of ostensibly honest botanical work was execrable. Recently I was going over some of his final leaflets, and I read his treatment of

Amorifera maldita

, which makes one feel like planting a specimen of same on his grave so he can spend eternity studying it more carefully.

Amorifera maldita

, which makes one feel like planting a specimen of same on his grave so he can spend eternity studying it more carefully.

Still, Colton Cates's greatest crime came not in his work but in his decision to reproduce. The less said about his offspringâin particular the reprehensible Slade Catesâthe better .

20

Profile #9620

Maximilian Unterdorf

Another botanical irritant, this one of the Teutonic variety. Unterdorf splits species left and right and left again, finding dramatic differences where none exist.

What on earth could account for this thuggish Hun's rampage across the hallowed grounds of responsible taxonomy? With most splitters, the cause is usually arrogance, leavened with a wholly inappropriate sense of certitude, although in Unterdorf's case, ineptitude may be an equal factor. Support for this hypothesis can be found in his abhorrent dichotomous key for

Lamides

, which induces its unsuspecting users to misidentify

L. dorothyi

as

L. bettyi

, and vice-versa. (I shall not even waste ink to point out how vulgar it is to name one's botanical discoveries after whichever comely “volunteer assistant” happens to be in the field with one at the moment.)

Lamides

, which induces its unsuspecting users to misidentify

L. dorothyi

as

L. bettyi

, and vice-versa. (I shall not even waste ink to point out how vulgar it is to name one's botanical discoveries after whichever comely “volunteer assistant” happens to be in the field with one at the moment.)

Unterdorf somehow has no shortage of young and curvaceous dabblers to accompany him as he roams the West whilst allegedly botanizing.

21

One imagines that in the musky air of his laboratory at the University of California-Lake Elsinore, these foolish girls clutch to his tweeds, sigh about how

fascinated

they are by his

work

,

only to return from the wilds sullied, red-faced, and full of his gametes. At most recent count, sixteen children on this continent (and devil knows how many in the Old Country) call this man Father. One fears one can scarcely put one's pencil down before one will have to pick it up again to mark the score-sheet as another poor lass's cries of labor pain fly to the winds in Tucson or Provo or Ensenada or Heidelberg or wherever else Unterdorf has set foot in his quest to name everything his lizard-lidded eyes fall upon, regardless of whether it is in need of naming.

21

One imagines that in the musky air of his laboratory at the University of California-Lake Elsinore, these foolish girls clutch to his tweeds, sigh about how

fascinated

they are by his

work

,

only to return from the wilds sullied, red-faced, and full of his gametes. At most recent count, sixteen children on this continent (and devil knows how many in the Old Country) call this man Father. One fears one can scarcely put one's pencil down before one will have to pick it up again to mark the score-sheet as another poor lass's cries of labor pain fly to the winds in Tucson or Provo or Ensenada or Heidelberg or wherever else Unterdorf has set foot in his quest to name everything his lizard-lidded eyes fall upon, regardless of whether it is in need of naming.

A hopeless, vile, and unrepentant splitter; as many bastards as he has produced, he has notched ten times that number in bastard species of the botanical variety.

Profile #121

Guy-Laurent Petitfour

In the human sense, Petitfour's accidental death

22

in 1919 at the age of forty-three was a tragedy. In the botanical sense, it was a blessing, and it ought to have been celebrated with a great feast, much dancing, and that jubilant ritual the Mexicans refer to as “pinyata.”

22

in 1919 at the age of forty-three was a tragedy. In the botanical sense, it was a blessing, and it ought to have been celebrated with a great feast, much dancing, and that jubilant ritual the Mexicans refer to as “pinyata.”

His limitations as a botanist aside, he was also a demented little man. Of his behavior in the field I can say little without risking much emotional distress to myself. To those of you who have heard the whispers that he customarily used his plant press in the service of onanism: I shall not be the one to disabuse you of this notion. Since our first and only expedition together, I have refused to handle any specimen collected by him or his assistants.

As if that were not enough: one morning when we were camped on the banks of the Rio Hondo, he delayed our departure by claiming extreme impaction of the colon, owing to a quantity of Mexican cheese of dubious provenance which he had ingested the night before. (I had not partaken, having the sense to limit my diet to tinned foods while in that primitive land.) He then volunteered the information that he needed to “dig himself out.” Perhaps I misunderstood his intentions, owing to his tortured English and lazy diction, but the image that his words conjured will haunt me until they plant my bones in the ground.

The former Mrs. Quilcock always professed respect and admiration for the constipated Frenchman, which I always found baffling, but then, she makes it a practice to search for the best in people. A rare quality indeed, especially in this line of work.

Profile #179

Earl Godfrey Orr

Even at his advanced age, E. G. Orr persists at inflicting his imbecilic work upon us. His “contributions” to systematic botany in generalâand to the study of the family

Proboscaceae

in particularâcan only be described as pestilential. An indefatigable supporter of Kingslee, he is also said to be a pederast.

23

Profile #222Proboscaceae

in particularâcan only be described as pestilential. An indefatigable supporter of Kingslee, he is also said to be a pederast.

23

Other books

BarefootParadise by J L Taft

Mick Sinatra 3: His Lady, His Children, and Sal by Mallory Monroe

A Joyful Break (Dreams of Plain Daughters) by Craver, Diane

Demons by John Shirley

Mistletoe Rodeo (Welcome to Ramblewood) by Amanda Renee

Heart's Haven by Lois Richer

The Touch by Colleen McCullough

What the Lightning Sees: Part Three by Louise Bay

The Diamond Rosary Murders by Roger Silverwood

Agent for a Cause (The Agents for Good) by Stanton III, Guy