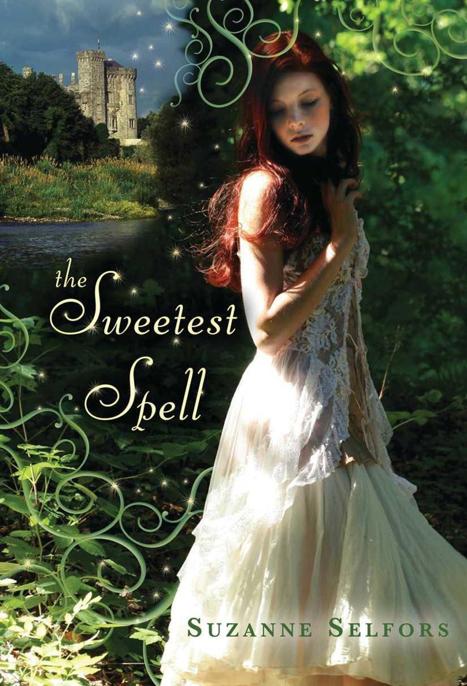

The Sweetest Spell

Read The Sweetest Spell Online

Authors: Suzanne Selfors

Sweetest

Spell

SUZANNE SELFORS

For Bob

Dirt-Scratcher Girl

Chapter One

I was born a dirt-scratcher’s daughter.

I had no say in the matter. No one asked, “Wouldn’t you rather be born to a cobbler or a bard? How about a nobleman or a king? Are you certain that dirt-scratching is the right job for you?”

If someone had asked, I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t have answered, “My heart is set on being a dirt-scratcher. I’m really looking forward to a life soured by hunger, backbreaking work, and ignorance. That sounds delightful. Sign me up.”

Oh, and I’m absolutely certain I wouldn’t have added, “Could you also give me some sort of deformity? Just to make things

interesting

.”

The midwife told me the full story of my birth, as much as she could remember. She said nothing out of the ordinary happened that evening. No blinding star appeared on the horizon, the world wasn’t darkened by an eclipse, time didn’t stand still—the sort of

thing that heralds the birth of someone really important. But the midwife boiled the water and counted the beats between my mother’s screams, and after I’d been pushed from the womb, the midwife wrapped me in a rag and carried me outside.

“She’s no good,” the midwife told my father.

“No good?” My father bowed his head and stared at the cracked leather of his boots.

“She’s not a keeper.” The midwife didn’t hesitate. In this time and place, decisions of life and death had to be made. “You must cast her aside, Murl Thistle.”

My father ran his callused hand over his face as if trying to wipe away the truth.

“She’s got a curled foot,” the midwife whispered. She’d whisked me out of the cottage before my exhausted mother could catch a glimpse of me.

Reaching ever so hesitantly, my father slowly peeled back the stained rag. Peering at my misshapen foot, sadness settled in his eyes. Learning your babe is not a keeper has to be the worst feeling in the world. He’d seen the deformity before and it sealed my fate. A dirt-scratcher’s daughter needed two strong feet. A curled foot would slow me down, would keep me from doing my fair share of work in the fields. I would be a burden, a gaping mouth to feed. I would never earn enough coin to buy myself a husband. No man would want me.

“Go tell your wife the babe was stillborn.” The midwife’s tone was matter-of-fact, for she’d learned that it was always best to lie to the mother. A mother, once she’s laid eyes on her child, will always

beg to keep it despite its defects. “I will take her to the forest, Murl Thistle.”

A quiet sound, like a wood dove’s coo, floated from my mouth. My father didn’t look at my face. Perhaps he figured that if he looked into my eyes, he would see that they were exactly like his eyes, and he’d want to claim me as his own. My father didn’t hold me. Perhaps he knew that if he felt the warmth that ebbed from my tiny body and if he felt the beating of my heart, I would become a keeper. I would become his daughter.

He turned away. “Do what you must,” he said. “I will tell my wife.” Then, with heavy footsteps, as if his legs were felled trees, he stepped into the cottage and closed the door.

My mother’s sobs seeped between the cottage stones as the midwife carried me away. The sun was setting, and she wanted to get some distance between the cottage and my fate. She didn’t want my parents to hear me cry out. Nor did she want them to accidently stumble upon my tiny bones one day.

Toward the forest the midwife hurried, keeping between the ruts worn into the road by the dirt-scratchers’ carts. The day’s heat was fading, but I was as warm as a stone taken from a fire. Images flooded the midwife’s mind of her own warm children tucked beside her at night. She pushed those images away as she passed the first tilled field, then the next. I wiggled in her arms but she offered no soothing words—what would be the point? Death was coming. In the best of circumstances it would be swift and merciful.

She turned off the road and started across a meadow, her skirt

swooshing through tall grass. The forest hugged the edge of the field like a dark curtain, hiding the creatures that lived within its depths. The midwife stopped. She didn’t dare go closer. She gently set me on the ground. The predators would come. They always did. And it would be as if I’d never been born.

Finding a clean spot on her bloodied apron, the midwife wiped sweat from her neck. Twilight would soon caress the sky and she needed to get home. She slid the rag free, exposing me so my scent would mix with the evening breeze. A brief twinge of pity pulled at her but she stopped herself from looking into my eyes. Pity wouldn’t help me.

The rag tucked under her arm, she left me to my fate. That was the end of her story.

The milkman told how he’d found me the next morning. But the in-between comes from my remembering. I know it sounds strange that a newborn babe could remember, but I do. I swear I do. To this day, it’s the brightest memory I have.

Four brown milk cows, having grazed in the field for most of the day, were on their way back to their barn when they caught my scent in the air. Usually wary of the forest’s edge, they moseyed up to me, their tails flicking with curiosity. Ignoring their instinct to return home, they stood over me, even as twilight descended. Even as the predators began to stir.

And so it was that four pairs of large, brown eyes were the first to look directly at me, and I met their gazes with an unblinking fascination. Four pairs of eyes, framed with thick lashes, were the first to acknowledge me, and I cooed with appreciation. One cow

gently nudged me from side to side while the others licked me clean. As night crept into the meadow, the cows settled in the grass, forming a protective circle. The ground absorbed their heat the way it had absorbed the sun’s heat, and warmth spread beneath me. I found a nipple and warmth spread throughout my little body.

And I, the babe who’d been cast aside, lived.

The only thing on my mind that morning was the upcoming husband market. It never failed to be the most exciting day of the year, promising passion, heartbreak, comedy, even murder. Aye, murder, because on a few occasions, disappointed women had turned on the highest bidder. Nothing else could compare to the husband market for sheer entertainment. My head swirled with excitement. That’s why I didn’t notice the cows until Father said something.

“Those creatures are at the window again.”

It wasn’t a fancy window for it had no glass, but it was a hole in the side of our cottage and I’d drawn the ragged curtain aside to let in some fresh air. Clearly the cows thought this was an invitation, for they stuck their noses through the hole and flared their wet nostrils. One white-faced, the other brown, they snorted for attention.

“I’ll take them back,” I said, scraping the last mouthful of

mashed potato from my bowl. When the cows showed up, which they did now and then, I always walked them home. It was the only way to get them to leave. They’d come to see me, after all.

After licking my spoon clean, I pushed back my stool and waited for Father’s permission.

“Go on then,” he grumbled, hunching over his bowl. His sharp shoulders pressed at the seams of his threadbare shirt. I hoped he’d look up and offer a reassuring nod, but he didn’t. He rarely looked directly at me. But I’d caught him a few times, staring as I stumbled across the field, sadness dripping off him like rain.

Everyone in the village of Root knew that my father had rejected me at birth. But he’d simply done what any other dirt-scratcher would have done. Food and shelter were precious and not to be wasted on those who couldn’t contribute. This was the way of my people. Over the generations, countless deformed babes had been fed to the forest. When the milkman found me, he knew I was Murl Thistle’s babe because my mother was the only woman who’d gone into labor that week. The villagers said my survival was a bad omen. Some kind of black magic had influenced the cows. It was unnatural.

I was unnatural

. That’s why villagers always kept a wary distance.

“I’ll be as quick as I can,” I said, pulling my shawl from its peg. There were kitchen chores to get to. Socks to wash. A donkey’s stall to be mucked out. The sun never stayed around long enough for all the work to get done. The precious time it would take for me to walk the cows back to the milkman’s land was

sacrificed because my father didn’t want to face the milkman’s temper.

“I got no time to chase after my cows,” the milkman had hollered at my father one day. “They stray, Murl Thistle, because that daughter of yours has unnatural power over them. If she doesn’t bring them back, I’ll complain to the tax-collector!”

As I hurried from the cottage, the white-faced cow stepped away from the window and greeted me with a soft moo.

“Hello,” I answered. The cow dipped her head and I kissed her wide brow. She smelled like grass and dirt and wind. I’d known this cow my entire life, and though the milkman never named his cows, I secretly called her Snow. Snow was the only cow left of the original four that had saved me.