The Swing Book (27 page)

Authors: Degen Pener

Suits:

Whatever style you choose—whether it be double-breasted or single, three-button or four, pinstripe, fleck, or a solid color

(blue serge was one of Cab Calloway’s favorites)—the most important consideration is fit. Back in the swing era, it was common

for men to have all their suits custom-made. “They called it a drape suit because the fabric was actually draped on the gentleman,”

says Savoia Michele, whose custom period-style suits can run up to two thousand dollars. Another source, in the LA area, is

Jorge Avalos of Tin Tan Tailor Made Suits in Long Beach who designs suits for such bands as Royal Crown Revue, Big Bad Voodoo

Daddy, and Eddie Reed. Of course, not everyone can afford custom work. But even off-the-rack vintage suits can run up to four

hundred, five hundred, or eight hundred dollars. So it’s worth making sure someone with a keen eye checks you out when you

try on the suit. You should also plan on taking it to a local tailor for some slight alterations to get it just right. For

a regulation forties look, the shoulders should be big. It should drape nicely down the body and come in at the hips, creating

a V-shape. Also, look out for things like exaggeratedly peaked lapels, pleated pockets, or jackets with belted backs, the

kind of detailing that makes a suit really special. As Duke Ellington and Billy Eckstine once proved, you can never have enough

suits. When the pair worked together at New York’s Paramount Theater, they engaged in a battle of the closets instead of a

battle of the bands. “For four weeks,” Ellington once recalled, “neither of us wore the same suit twice.… People were buying

tickets just to see the sartorial changes.”

Suspenders:

It’s a sorry sight to see a pair of pants left to hang by themselves. They need suave suspenders holding them up to really

fly. Make sure to choose the classier ones that attach to the pants with buttons, not clip-ons. And if you can find authentic

forties pairs—they’re stretchier and narrower (three-quarters to one inch wide) than most kinds today—grab ’em. “You don’t

need extra-wide suspenders when you’ve got a wild tie on,” says Michael Gardner, president of Siegel’s department store. What’s

a snazzy color combination? A black dress shirt with total-contrast white suspenders.

Ties:

In the 1940s, neckties were the undisputed kings of menswear. Sherman Billingsley, owner of the exclusive Stork Club, was

renowned for his collection of more than three thousand. Men even belonged to tie-swapping clubs, and it’s not hard to see

why. To call them art wasn’t an overstatement. Inspired by everything from deco to cubism to surrealism (Salvador Dali did

his own line of ties, which today can cost more than four hundred dollars), ties were wild, oversized, crazy, beautiful, loud,

you name it. Indeed, some had such inspired patterns that they were called ham-and-eggs ties “upon which sloppy eating wouldn’t

be noticed,” according to

Fit to be Tied,

a must-have coffee table book on neckwear of the era. Among the many types worth searching out are classic art deco styles

with lightning bolts and leaping gazelles; hunting and fishing motifs; tropical styles with palm trees or Hawaiian prints;

and landscapes, from scenes of San Francisco to painted-desert sunsets. And if you really want to spend the money, track down

such hard-to-find winners as a Countess Mara signature tie, a classic California hand-painted number (the authentic ones actually

say Hand-Painted on the back); a pinup girl tie (some of the coolest have the cutie printed inside the back of the tie); and

a line called Personali-ties that included ties endorsed by Bob Hope.

Be aware that the most authentic ties from the war years are made of rayon, not silk (which was requisitioned to make parachutes).

Make sure that the tie is the standard forties width, about four inches, or even four and a half inches, across at the widest.

And don’t worry if your new find seems really short once you tie it. It was designed that way to be worn with those high-waisted

pants. To stand out from the crowd, wiseguys and entertainers used to wear them even shorter.

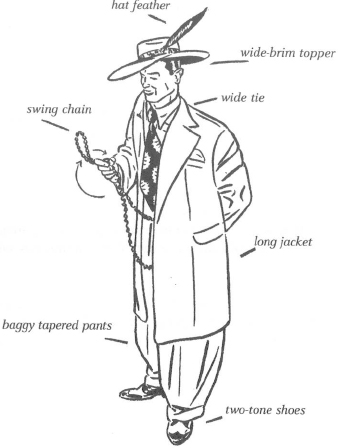

Zoot Suit:

The height of sartorial indulgence, zoot suits have almost become cliché emblems of the swing revival. But in their time

they were powerful social statements of defiance, predating by decades such shock-the-bourgeoisie fashions as long hair on

hippies in the sixties and multiple piercings in the nineties. Worn by disadvantaged and disaffected Hispanic and African-American

youths in Los Angeles and Harlem, the zoot suit was an absurdly exaggerated look. Suit coats had peaked lapels and high shoulders

and dropped all the way to the knees. Pants began at the rib cage, flowed out at the knees, and tapered in dramatically at

the ankles. “It was quite a real, real zinger as a suit,” Cab Calloway has said. Adding to the extravagance were long chains,

wide-brimmed hats topped with feathers, pointed shoes, and oversized cuff links. The outfit even required a certain stance.

“Hat angled, knees drawn together, feet wide apart, both index fingers jabbed toward the floor,” wrote Malcolm X in his autobiography,

recalling how a zoot suit was worn. “The long coat and swinging chain and the Punjab pants were much more dramatic if you

stood that way.”

Such a display, however, provoked a harsh reaction from mainstream society during the war years. Zoot suits flaunted reams

and reams of material at the same time that consumer goods, especially fabrics, were being rationed. Inevitably, they were

deemed an unpatriotic affront to the war effort. “To wear clothes that used up that much fabric represented a way of saying

we don’t care,” says Annamarie Firley of Revamp. By 1943 the Los Angeles City Council had gone so far as to effectively make

them illegal. Quickly the conflict turned violent, as servicemen stationed in LA began beating up zoot wearers and destroying

their suits. Police often looked the other way. At the conclusion of the average rumble, zoot suiters more often than not

were the ones who ended up going to jail. Incidents spread to New York, Philadelphia, San Diego, and Detroit. (For more on

the history of the zoot suit, check out the essay “The Zoot Suit and Style Warfare” in the anthology

Zoot Suits and Second-Hand Dresses

or rent the 1981 movie

Zoot Suit

starring Edward James Olmos.)

The Zoot-Suiter

Today an authentic vintage zoot from the forties is as impossible to find as a live Elvis. Very few still exist, and most

that do reside in museums. “I’ve been in this business ten years and I’ve never seen one,” says Graciela Ronconi of Guys and

Dolls. But many stylin’ reproductions are available, from stores like El Pachuco, Siegel’s (which even does zoot tuxedos in

all white), and Suavecito, at prices from two hundred dollars to five hundred dollars and up. Colors run the gamut: black

or white, royal blue or hot red, and, of course, pinstripe. Caution: Beware of counterfeiters trying to ride the trend: “People

are taking a coat and adding six to eight inches to it and calling it a zoot suit,” says Smiley Pachuco.

Bow Ties:

They weren’t just for eggheads. Cab had his wild ones, and Nat King Cole and Fats Waller were just as spiffy in more traditional

bow ties. And while you can buy clip-ons, wouldn’t you be more proud of yourself if you learned how to tie a real one?

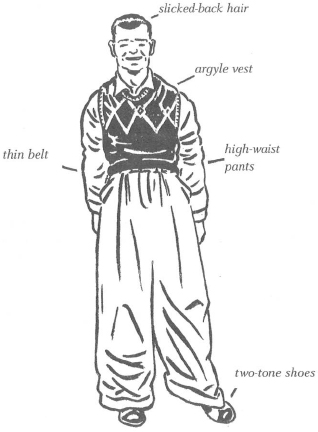

Belts:

The belts of the period were usually skinny, not wide. “With those thin belt loops, you wore a belt of between half an inch

and an inch,” says Savoia Michele. Some of the sharpest come in black alligator or white leather. “The shoes to wear in the

summer were white bucks. And men always matched their belts to their shoes,” he adds.

Casual Shirts:

After World War II, many men stopped wearing ties after work and the leisure era was born. Among the cool offerings from

the period are gabardine shirts that have a tab at the collar instead of a buttonhole, bowling shirts, short-sleeve camp shirts,

Cuban-style embroidered guayaberas, and the ever-popular Hawaiian shirts. Companies making quality reproductions include the

Hi-Ball Lounge, Cruisinusa, Swave and Deboner, Devlin (incredible two-tone shirts), Johnny Suede (look for their flaming martinis),

Siegel’s (which does a great tiki number), Tr$$$ac Edwards, and the most authentic, Da Vinci, which reproduces shirts based

on their own original patterns from the period.

Chains:

Up to sixty inches long, chains are the accessory of choice for a zoot suit. “The chain is part of the uniform,” says Smiley

Pachuco. “The coat should not be buttoned, so that the chain shows.” To jazz the look up even further, consider buying a double,

triple, or even quadruple chain.

Cuff Links:

To run with your own Rat Pack, you’ve gotta show cuff. And that means amassing your own collection of cuff links (Sinatra’s

hoard was legendary). There are thousands upon thousands of designs out there. So take the time to look through those glass

cases in the thrift shop for a few pairs that suit your personality—or your mood. For snappy reproductions, check out Winky

and Dutch’s cool sets with everything from pinups to martini glasses to dice on them. And don’t be afraid of oversized cuff

links. The real zoot-suiters were known for strutting down the street wearing rock-sized pairs on their wrists.

Hair:

For a basic forties look, just keep your hair short and slick it back (with either grease or pomade). To get fancy, try a

pompadour—zoot-suiters wore ones with ducktails. In the fifties (and on the New Morty Show’s Morty Okin) they were higher.

But whatever you do, don’t go to a salon for a cut. “If you are a guy, go to the oldest barber you can find in town,” says

retro hairstylist Kim Long, owner of San Francisco’s W.A.K. Shack. “The older barbers will know what to do.” And for real

authentic flair, you may even want to try the pencil-thin mustache seen on Cab Calloway and Nat King Cole. Talk about walking

a thin line.

Hollywood Jackets:

Also called leisure jackets, Hollywood jackets were casual unconstructed sport coats, made of rayon or wool gabardine, that

came into popularity in the late 1940s. The classiest boast a two-tone look, such as a cream jacket with contrasting brown-and-cream

houndstooth sleeves and collar. Some were also belted. The most desired vintage labels are Mr. California and a line endorsed

by bandleader Xavier Cugat. Jackets by C. Joseph, a label available at San Francisco’s Martini Mercantile, are among the best

reproductions.

Pocket Squares:

Frank Sinatra was fastidious about pocket squares. He’d even go up to other guys and fix ’em if they weren’t worn right.

Pocket squares should puff out from the jacket’s pocket a bit, while simple white handkerchiefs are worn crisply folded. Pocket

squares come in all colors and fabrics (the classic is silk). Choose one that coordinates especially well with your tie, along

with your shirt and jacket.

Socks:

Ever thought you’d be wearing men’s hosiery? Yeah, you heard it right. Guys often wore just as much nylon as gals back in

the forties. The favorites were sheer nylon ribbed socks, often humorously referred to today as pimp socks. The best finds

are dead-stock—from all-American brands like Gold Toe—or the well-made reproductions by Stacy Adams. “They come in every color

you could think of,” says Siegel’s Michael Gardner, who sells them in traditional black or brown, but also in red and sapphire.

“People tend to forget that in fashion in the thirties and forties, color was really big.”

Spats:

Spats were originally designed to protect one’s shoes while walking in rainy weather. These leather ankle cover-ups, usually

chosen to complement your shoes, give an instant period feel.

Sweaters:

Hey, junior, want to be the B.M.O.C. (Big Man on Campus)? Throw on a collegiate-style sweater such as an argyle vest, a long-sleeved

tennis sweater, or a pullover with an oversized varsity letter on the front. You can really make the grade by topping it off

with a smart bow tie.

Sweat Rags:

A sweat rag isn’t as unimportant (or gross) as it sounds. If you’re one of those guys whose mop-top sweats too much from

doing the hop, you’d better carry a rag to stay neat. But no need to get fancy here. Just grab a small white towel from the

gym and tuck it into your pocket. Or better yet, stuff it in the back of your suspenders.

Tattoos:

Many neoswing observers have remarked on the seeming incongruity of tattooed Gen X-ers wearing forties clothes. But it’s

not such an anachronistic mix after all. Before tattoos ruled the mosh pit, they were the province of sailors and sharpies

during the war years and earlier. “The tattoo thing was a big part of the swing period,” says Savoia Michele. “They were called

flash tattoos. It was all about pinup girls and dice designs.”