The Taste of Conquest (2 page)

Read The Taste of Conquest Online

Authors: Michael Krondl

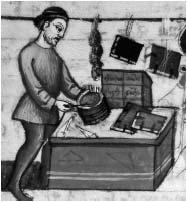

I’d love to invite these academics to the Sultan restaurant. Perhaps then they would understand how perfectly credible is the medieval account that records the use of a seemingly spectacular two pounds of spices at a single bash. The figure comes from a manuscript called the

Ménagier de Paris

penned by an affluent, bourgeois functionary for his young wife in the late thirteen hundreds and includes all sorts of advice, including just what you needed to buy to throw a party. As an example, the writer describes an all-day wedding feast consisting of dinner and supper for forty and twenty guests, respectively, as well as some half dozen servants. The shopping list does indeed include a pound of ginger and a half pound of cinnamon as well as smaller quantities of long pepper, galingale, mace, cloves, melegueta, and saffron. But it also calls for twenty capons, twenty ducklings, fifty chickens, and fifty rabbits as well as venison, beef, mutton, veal, pork, and goat—more than six hundred pounds of meat in all! What’s extraordinary about this meal is not the quantity of spice—at most, about a half teaspoon of mostly sweet spices for each pound of meat—but the extravagance of the entire event. If this is an orgy of food, the spices would hardly qualify as more than a flirtation.

Still, even that half teaspoon of spice would be unusual in contemporary French or Italian cooking, though it would scarcely merit mentioning at an Indian restaurant. To make the Balti

gosht,

you use way more seasoning, about a half ounce of spices (or roughly two level tablespoons) for every pound of meat. So it may well be that my medieval knight would have found my

gosht

hard going even for his developed palate. I can only imagine what the academics would say.

T

HE

N

EED FOR

S

PICE

A great deal of nonsense has been written by highly knowledgeable people about Europeans’ desire for spices. Economic historians of the spice trade who have long mastered the relative value of pepper quintals and ginger kintars (both units of weight) and effortlessly parse the price differential of cloves between Mecca and Malacca will typically begin their weighty tomes by mentioning, almost in passing, the self-evident fact that Europeans needed spices as a preservative or to cover up the taste of rancid food. This is supposed to explain the demand that sent the Europeans off to conquer the world. Of course, the experts then quickly move on to devote the rest of their study to an intricate analysis of the supply side of the equation. But did wealthy Europeans sprinkle their swan and peacock pies with cinnamon and pepper because their meat was rank? The idea is an affront to common sense, to say nothing of the fact that it completely contradicts what’s written in the old cookbooks.

Throughout human history, until the advent of refrigeration, food has been successfully preserved by one of three ways: drying, salting, and preserving in acid. Think prunes, prosciutto, and pickles. The technology of preserving food wasn’t so different in the days of Charlemagne, the Medici, or even during the truncated lifetime of Marie Antoinette, even though the cooking was entirely different in each era. The rough-and-ready Franks were largely ignorant of all but pepper. In Renaissance Italy, ginger, cinnamon, nutmeg, saffron, and cloves adorned not merely the tables of merchants and potentates but also found their way into medical prescriptions and alchemical concoctions. Spices were even used as mouthwash. And then French trendsetters of the waning seventeenth century, after their own six-hundred-year dalliance with the aromas of the Orient, turned away from most spices to invent a cuisine that we might recognize today. So if spices were used for their preservative qualities, why did they stop using them? The French had not discovered some new way of preserving food. There was a shift in taste, certainly, but it was the same kind of change that happened when salsa replaced ketchup as America’s favorite condiment. There were many underlying reasons for it. Technology wasn’t one of them.

Old cookbooks make it clear that spices weren’t used as a preservative. They typically suggest adding spices toward the end of the cooking process, where they could have no preservative effect whatsoever. The

Ménagier,

for one, instructs his spouse to “put in the spices as late as may be, for the sooner they be put in, the more they lose their savor.” In at least one Italian cookbook that saw many editions after its first printing in 1549, Cristoforo Messisbugo suggests that pepper might even hasten spoilage.

Perversely, even though spices weren’t used in this way in Europe, they could have been. Recent research has identified several spices that have powerful antimicrobial properties. Allspice and oregano are particularly effective in combating salmonella, listeria, and their kind. Cinnamon, cumin, cloves, and mustard can also boast some bacteria-slaying prowess. Pepper, however, which made up the overwhelming majority of all European spice imports, is a wimp in this regard. But compared to any of these, salt is still the champion. So the question remains, why would Europeans use more expensive and less effective imports to preserve food when the ingredients at hand worked so much better?

But what if the meat were rancid? Would not a shower of pepper and cloves make rotten meat palatable? Well, perhaps to a starved peasant who could leave no scrap unused, but not to society’s elite. If you could afford fancy, exotic seasonings, you could certainly afford fresh meat, and the manuals are replete with instructions on cooking meat soon after the animal is slaughtered. If the meat was hung up to age, it was for no more than a day or two, but even this depended on the season. Bartolomeo Scappi, another popular writer of the Italian Renaissance, notes that in autumn, pheasants can be hung for four days, though in the cold months of winter, as long as eight. (When I was growing up in Prague, my father used to hang game birds just like this on the balcony of our apartment, and I doubt that our house contained any spice other than paprika.) What’s more, medieval regulations specified that cattle had to be slaughtered and sold the same day.

Not that bad meat did not exist. From the specific punishments that were prescribed for unscrupulous traders, it is clear that rotten meat did make it into the kitchens of the rich and famous, but then it also does today. The advice given by cookbook author Bartolomeo Sacchi in 1480 was the same as you would give now: throw it out. The rich could afford to eat fresh meat and spices. The poor could afford neither.

Wine may have been another matter. For while people of even middling means could butcher their chicken an hour or two before dinner, everyone, including the king, was drinking wine that had been stored for many months in barrels of often indifferent quality. Once a barrel was tapped, the wine inside quickly oxidized. Especially in northern Europe, where local wine was thin and acidic while the imported stuff cost an arm and a leg, adding spices, sugar, and honey must have quite efficiently improved (or masked) the off-flavors.

Rather than trying to discover some practical reason that explains the fashion for spices, it’s probably more productive to look at their more ephemeral attributes. One credible rationale for a free hand with cinnamon and cloves is their very expense.

Spices were a luxury even if they were not worth their weight in gold, as you will occasionally read. In Venice, in the early fifteenth century, when pepper hit an all-time high, you could still buy more than three hundred pounds of it for a pound of gold. And while it’s true that a pound of ginger could have bought you a sheep in medieval St. Albans, that may tell you more about the price of sheep than the value of spice. Sheep in those days were small, scrawny, plentiful, and, accordingly, cheap. You will also read that pepper was used to pay soldiers’ wages and even to pay rent. But once again, this requires a little context. Medieval Europe was desperately short of precious metals to use as currency, and if you needed to pay a relatively small amount (soldiers didn’t get paid so well in those days), there often weren’t enough small coins to go around. Thus, pepper might be used in lieu of small change. But sacks of common salt were used even more routinely as a kind of currency in the marketplace.

All this is to say that spices weren’t the truffles or caviar of their time but were more on the order of today’s expensive extra-virgin olive oil. But like the bottle of Tuscan olive oil displayed on the granite counter of today’s trophy kitchens, spices were part and parcel of the lifestyle of the moneyed classes, as much a marker of wealth as the majolica platters that decorated the walls of medieval mansions and the silks, furs, and satins that swaddled affluent abdomens.

In those days, a person of importance could not invite you to a nice, quiet supper of roast chicken and country wine any more than a corporate law firm would invite a prospective client to T.G.I. Friday’s. As the

Ménagier

’s wedding party makes clear, there was nothing subtle about entertaining medieval-style. Our own society has mostly moved on to other forms of conspicuous consumption—though you can still detect an echo of that earlier era in some high-society weddings that cost several times a plumber’s yearly wage. But much more so than today, the food used to be selected in order to impress your guests. The more of it and the more exotic, the more it said of your place in the pecking order. When Charles the Bold, the powerful Duke of Burgundy, married Margareth of York in 1468, the banquets just kept coming. At one of them, the main table displayed six ships, each with a giant platter of meat emblazoned with the name of one of the duke’s subject territories. Orbiting these were smaller vessels, each of which, in turn, was surrounded by four little boats filled with spices and candied fruit. Spices, of course, literally reeked of the mysterious Orient, and their conspicuous consumption was surely a sign of wealth. When the duke’s great-grandson, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, visited Naples some years later, he was served peacocks and pheasants stuffed with spices. As the birds were carved, the guests were enveloped by the Edenic scent. The idea was nothing new; one of Charles’s predecessors, Emperor Henry VI, in Rome for his coronation in 1191, was paraded down streets that had been fumigated by nutmegs and other aromatics when he arrived.

In the late Middle Ages, when the increasingly prosperous bourgeoisie began to be able to afford a little ostentatious display of their own, the feasts of the aristocrats had to become even more fabulous, the spicing more refined, the dishes more exquisite and artfully designed. And just to make sure the entire populace would know how fantastic was the prince’s inner realm, the entire dinner might be put on display for the hoi polloi. “Before being served, [the dishes] were paraded with great ceremony around the piazza of the castle…to show them to the people that they might admire such magnificence,” recounts Cherubino Ghirardacci, who witnessed a wedding party hosted by the ruler of Bologna in 1487. Our reporter does not mention the smell, but surely the abundance of expensive meat with a last-minute sprinkling of spice gave forth an aroma that broadcast the ruler’s power even more effectively than the grand dishes glimpsed from across the road.

It was a medieval commonplace that people of different status and position not only deserved but required different foods. A peasant might fall gravely ill from eating white bread and spiced wine rather than the appropriate gruel and ale. A monk would certainly suffer painful indigestion from eating peppered venison, a food more properly reserved for knights. These rules were accepted as being part of divine providence. Inasmuch as there was a natural order among the beasts, each of which was assigned its appropriate food by the Creator, so each human being was assigned his position in the divine plan. Something of the kind still exists today in food attitudes among observant Hindus, with each particular caste having its own rules regarding what may or may not pass their lips. For an upper-caste Brahmin to eat food that is forbidden or inappropriately prepared is to disrupt the order of the universe. A similar connection existed between food and religion in Christendom before Martin Luther upset the cart. When Saint Benedict set up his monastic communities in the early sixth century, he specified just what his monks could eat and when. (It wasn’t much and it wasn’t too often.) Every Catholic had to conform to the religious calendar, but within that generalized scheme, each social stratum had different rules. The Italian preacher Savonarola, best known for castigating Renaissance Florentines for their ungodly ways, also had opinions on the appropriate dining habits of various castes. “Hare is not a meat for Lords,” he writes. “Fava beans are a food for peasants.” Beef was apparently okay for artisans with robust stomachs but could be consumed by lords and ladies only if corrected with appropriate condiments.