The Taste of Conquest (20 page)

Read The Taste of Conquest Online

Authors: Michael Krondl

B

EYOND

G

OOD

H

OPE

Looking down from the

castelo,

it would appear no more than a quick scramble to the Praça do Comércio, where the king’s harborside palace used to stand. In fact, it is a long, circuitous descent down winding alleys and precipitous stairs. These days, the vast, charmless square is mostly desolate except for the occasional camera-toting visitor and the itinerant street peddler hawking fake Armani sunglasses. Under the grocer king and his immediate successors, this used to be the royal residence’s busy front yard and was accordingly referred to as Terreiro do Paço (literally, “Palace Grounds”). Old illustrations show grand parades in honor of visiting potentates filling the field. Temporary grandstands were erected here to give a better view of heretics burned alive at the frequent and well-attended autos-da-fé. I’ve been told that visitors occasionally comment on the resemblance of the Praça do Comércio to the Piazza San Marco. It is true that both are more or less right on the water, both have monotonous three-story neoclassical façades defining three sides. There are no famous cafés here, though, and no pigeons. Nevertheless, it’s worth noting that Lisbon, just like Venice, turns her back to the mainland to greet the sea. And in much the way the doge’s palace stood guard over the Adriatic harbor, the king’s palace stood sentry at his realm’s front gate.

But the Portuguese monarch was a different sort of creature than the CEO of Venice Inc. It’s almost as if the local topography reflected the way decisions were made in each town. Like Lisbon’s tumbling vertical façade, here, all the power and the glory cascaded down from the king, while in Venice (and Amsterdam, too, for that matter), wealth and influence spread horizontally, much as the watery city spread across the lagoon. But that may just explain why the Portuguese pioneered the direct route to India. It’s hard to see how anyone but an absolute monarch could have mustered the resources necessary to get the job done.

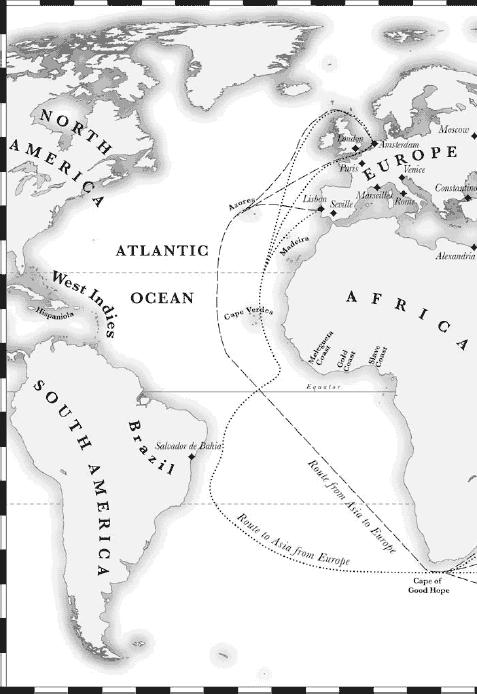

At Lisbon’s Museu de Arte Antiga, there is a series of fifteenth-century panels that might as well be a family portrait. Here is Henrique, the Navigator Prince, doughy and wry. Nearby is his nephew King Afonso V in a fabulous tunic of purple and green velvet with his wife, Isabel, in a gorgeous scarlet dress. (It makes you wonder how many shiploads of melegueta paid for those fabulous outfits.) Their son, the future João II, is just behind his father—a pudgy preteen with tousled hair. His almond eyes show no hint of his later Machiavellian streak. Yet who knows how far the Lusitanians would have gone if it hadn’t been for this ruthless and determined young man? At the time, not everyone in Portugal thought the Atlantic explorations were a good idea. King Afonso, for one, was never much interested in the Indian project. João, though, had none too subtle ways of convincing his opposition. Once he assumed the throne in 1481, he beheaded his most prominent opponents. An uncooperative bishop perished in a cistern. João personally stabbed to death one of his detractors. Even before he sat in his father’s seat, he was, by all accounts, fixated with reaching India. The obsession was apparently born some years earlier when, as crown prince, he secured the African spice and gold monopoly from the king. Then, once he held the reins of power, João II pursued the search for a southern passage to India with all his resources. And finally, when Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope, the way to India’s perfumed riches was clear.

Among the many hangers-on at Paço da Ribeira during João II’s rule was a Genoese navigator named Christopher Columbus. He had married into a Portuguese family

*23

and had his own ideas about reaching the Spice Islands. Contrary to what you may have been taught in elementary school, educated people did not think the world was flat in the Renaissance. There was, however, no consensus about just how big the globe was. According to one eminent Florentine geographer of the time, the earth was some ten thousand miles around the equator. (The actual distance is closer to twenty-five thousand.) Using this number, Columbus made the perfectly reasonable calculation that you could get to the Indies much faster by sailing west than by going south and east. There is some indication that João didn’t cotton much to the Italian adventurer on a personal level, but what eventually damned his proposal in Portuguese eyes was the preposterousness of the numbers. The frequent trips down the coast of Africa had given Portuguese navigators a pretty good sense of how big the earth was from pole to pole. If Columbus’s numbers were to be believed, the earth would have the improbable shape of an upended football. All the same, the king apparently took the idea seriously enough to have a commission look into it. They gave it a thumbs-down.

There may have been another reason why João was none too interested in going west. He may already have known what was there. Hernâni Xavier, for one, is convinced that two Portuguese maps show Brazil as early as the 1430s. But even if those maps are discounted, other circumstantial evidence all but proves that the Portuguese had at least some idea of the Americas before Columbus’s voyage. Portuguese sailors certainly spent the years between Dias’s discovery of the cape route and da Gama’s epochal voyage exploring the southern Atlantic, and given the currents and winds, it’s almost impossible that they didn’t at least sight South America. This is the likely reason why, in the 1494 treaty of Tordesillas, which divided up the world between Portugal and Spain, João fought tooth and nail to have the dividing line moved west. This just happened to place Brazil in the Portuguese sphere—six years before Brazil was officially discovered! But, at least for the moment, João knew that he did not have the resources to simultaneously explore a new world and pursue the pepper project in the East.

Spurned in Lisbon, Columbus went knocking on Isabella’s door in neighboring Castile, talked the queen into backing his plan, and the rest, as they say, is history. It all seems inevitable now, the partnership of Columbus and Isabella and the subsequent Spanish conquest of the New World, but at the time, it seemed an unlikely scenario. The Castilians had never been especially interested in the Atlantic, busy as they were with conquests back home. But once Dias had shown the feasibility of the cape route, the Spanish monarchs must have felt a certain urgency to act so that they wouldn’t lose out to their neighbors in any potential spice bonanza. This insecurity, this need to keep up with the Joãos, must have helped convince the queen next door to invest in the Genoan’s scheme. Columbus, in the meantime, was so convinced of his numbers that even after several trips to the West Indies, he would never admit that he had not found the fabled East. Not only did he insist on calling the indigenous peoples “Indians” and their islands the “Indies,” he came back with spices that he called pepper (

pimienta

), which were in fact capsicums and allspice. (The Spanish continue to call the latter

pimienta dulce

or

pimienta de Jamaica.

) Isabella was not impressed. When she found out that Vasco da Gama had returned from Calicut with the real thing, she sent for Columbus, who was on his third voyage to the Antilles at the time. Subsequently, the Genoan was brought home in chains and stripped of his titles and income. As far as the Castilian queen was concerned, his voyages were failures, the route to the Indies and their aromatic riches now in firm possession of the Portuguese. In Lisbon, Vasco da Gama would receive precisely the same titles (in imitation of the Castilian model) that Columbus had lost: those of admiral and viceroy of India.

Vasco da Gama set sail from the Lisbon suburb of Restelo on July 8, 1497, with a small flotilla of two

naus,

the

São Gabriel

and

São Rafael,

and a caravel, the

Bérrio,

dispatched by the king, according to an anonymous chronicler of the voyage, “to make discoveries and go in search of spices.” King João II was fated never to see those sails emblazoned with the Crusaders’ cross swell with the Atlantic wind. He had died two years earlier, at the age of forty. The day he had been planning for all his life was witnessed by his cousin and brother-in-law, Manuel I. Apparently, João didn’t think much of his wife’s brother (he made an aborted attempt to have his illegitimate son declared heir), which may explain, at least in part, why King Manuel worked so hard to outstrip his predecessor’s legacy. It must have rankled him that they dubbed him “the Fortunate” while João had been called “the Perfect Prince.”

We know quite a lot about Vasco da Gama’s fortunate royal patron, but the young explorer is a bit of a cipher. According to records, da Gama was only twenty-eight when he commanded that first mission to India. He was a middle son of middling aristocracy from the southern seaport town of Sines. While most definitely not a professional seaman, he seems to have had some experience serving in coastal missions under João’s administration. In later years, he had a reputation for being temperamental and capricious. However, on this first journey, the young captain-general comes across as so cautious as to verge on paranoia—at least when dealing with the locals in the Indian Ocean.

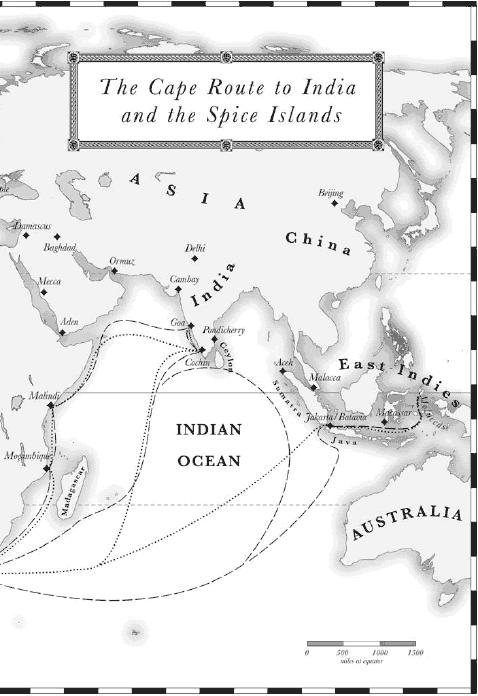

Da Gama’s ships carried provisions for three years, guns and gunners, interpreters, musicians and priests, and a few convicts (death-row inmates who had their sentences commuted to naval service) for some of the riskier tasks. The commander also carried a royal letter addressed to Prester John. Oddly, given its ostensible mission, the armada was surprisingly devoid of trade goods. The ships set course straight across the Atlantic, then back down to the Cape of Good Hope, and up to the city of Malindi, about halfway up Africa’s eastern coast in what is today’s Kenya.

By the time they reached Malindi on the eve of Easter 1498, more than nine months after setting sail, da Gama’s sailors had been suffering weeks of dehydration and dying of scurvy left and right. Several close calls with none-too-friendly natives along the East African coast had convinced them that no one could be trusted, so even in Malindi, where their reception was cordial, the Lusitanian adventurers kept a wary distance. Here, they took on fresh food and water, and equally important, they hired a Gujarati pilot to guide them across the Indian Ocean to Calicut. The pilot, though Muslim, supposedly even spoke some Italian! The rest of the trip was thankfully uneventful. The fleet reached Calicut in a mere twenty-six days on May 18, 1498, arriving just in time to be drenched by the southern Indian monsoon.

The Portuguese did not make a great impression on the locals when they arrived in India.

What came next was more farce than high drama. After his close shaves along the African coast, da Gama had no intention of putting himself at risk. That’s what the onboard convicts were for. So the first Portuguese conquistadores sent out to meet the legendary Indians were a couple of jailbirds. When they finally tracked down someone they could talk to, they also turned out to be foreigners—mainly, two Tunisians who just happened to speak Castilian and Genoese. Not surprisingly, the Arabs were none too pleased to see these all-too-familiar infidels. “May the Devil take you! What brought you here?” was their unsubtle greeting. To which the cons offered the oft-quoted reply “We come in search of Christians and of spices.” That first Calicut visit was not terribly successful on either account. Later visits would prove much more lucrative—at least, when it came to the spices.