The Temptation of Elizabeth Tudor (43 page)

Read The Temptation of Elizabeth Tudor Online

Authors: Elizabeth Norton

The Duke of Northumberland’s triumph was brief, for the young king fell ill at Easter 1552, failing to recover and dying at the age of fifteen the following year. For Elizabeth, Edward’s death changed everything. Her half-sister Mary was thirty-seven and unmarried when she overthrew Jane Grey (who was by then Northumberland’s daughter-in-law) to take the throne – and began the return of the kingdom to the religious embrace of Rome. Northumberland surrendered, was quickly tried for treason, and executed on 22 August 1553.

During Mary’s reign, Elizabeth’s security was by no means guaranteed, and she fell under suspicion. In March 1554, after the defeat of a rebellion led by Sir Thomas Wyatt against Mary’s imminent marriage to Philip II of Spain, the queen ordered her sister’s imprisonment in the Tower, suspecting her of involvement (although Wyatt never implicated her). In the time of her greatest peril, Elizabeth’s thoughts turned to Thomas Seymour. Hoping to delay her departure to prison, she wrote her famous ‘tide letter’ to Mary. In it, she referred to the quarrel between Seymour and Somerset, blaming it on false reports being made to the Protector of his brother’s conduct. She hoped that, unlike in this case of brothers, ‘the like evil persuasions persuade not one sister against another’.

38

If only Somerset had agreed to meet his brother. Elizabeth was released from the Tower in May 1554, initially moving to Woodstock, where she remained closely monitored.

Elizabeth was at Hatfield in November 1558 when she learned of Mary’s death and her own accession to the throne. Falling to her knees, she cried out that ‘this is the work of the Lord, and it is wonderful in our sight’.

39

In recognition of his long and loyal service, Thomas Parry was appointed to the important role of Comptroller of the Household, while his wife, Lady Fortescue was also rewarded, becoming one of Elizabeth’s senior ladies in 1558.

40

Kate Ashley was appointed as Chief Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber when Elizabeth became queen, becoming one of the most influential women in England at a stroke.

41

She remained in office until her death in 1565, when, finally, quiet Blanche Parry succeeded her as the queen’s closest confidante.

In spite of Elizabeth’s new status in 1558, Kate was far from done with matchmaking. It was obvious to all that Lord Robert Dudley, who resembled Thomas Seymour both in looks and character, had attracted the queen. Kate favoured him as her mistress’s husband and set about trying to persuade her former charge as to his merits. Elizabeth, however, was older and wiser. ‘Dost thou think me so unlike myself, and so unmindful of my Royal Majesty, that I would prefer my servant, whom I myself have raised, before the greatest princes of Christendom, in my choosing of an husband?’

42

Kate said no more. Nonetheless, one of Elizabeth’s last suitors, Sir Walter Raleigh, owed his arrival at court to the queen’s former lady mistress – for he was Kate’s great-nephew.

43

John Astley remarried after Kate’s death and produced a family. His young wife – who this time pronounced his last name correctly – was the daughter of Lord Thomas Grey, the man who had persuaded Seymour to hand himself in. Astley served Elizabeth as her Master of Jewels to die a wealthy and prominent individual in 1596.

44

Elizabeth eventually ruled England for more than forty years, surprising her contemporaries by failing to marry. She had learned well the lessons of her youth, seeming to have acquired ‘wisdom beyond her age’ even by the time of her accession.

45

As queen, she made no recorded mention of Thomas Seymour. He was nearly a decade dead by the time she gained the throne – but far from forgotten by all.

Not everyone fell away from Seymour at his fall. The faithful John Harington’s loyalty ensured him ten months in the Tower. He was eventually released in October 1549.

46

He remained in touch with Elizabeth, and in Mary’s reign he was imprisoned again – for carrying a letter to the princess when she was in disgrace.

47

During Elizabeth’s rule, he kept out of trouble and lived to a ripe old age; but he never forgot his devotion to Thomas Seymour.

According to his son, also named John,

*4

only a week before his death in 1582 John Harington senior carefully wrote out the names of all those who were still living ‘of the old Admiralty (so he called them that had been My Lord’s men)’.

48

Members of this exclusive club stuck together for over thirty years after the loss of their master. Thirty-three were still living in 1582, representing a diverse sub-set of society, since, as the younger Harington recalled, ‘many were knights and men of more revenue than himself [the elder John Harington], and some were but mean men, as armourers, artificers, keepers, and the farmers; and yet the memory of his service, was such a band among them all of kindness, as the best of them disdained not the poorest’. Thomas Seymour had been the common bond for these men, and they continued to cherish him, long after his demise.

In 1567, John Harington even presented a portrait of Thomas to the queen, with two poems inscribed on either side of the former Admiral’s head.

49

Both poems praised Seymour, the second recording that he was ‘of person rare, strong limbs, and manly shape’. Harington recalled him as ‘of friendship firm’, both wise and brave. He was, Harington claimed, ‘a subject true to king, and servant great’. ‘Yet against nature reason and just laws / His blood was spilt, guiltless without just cause’. Elizabeth accepted the painting – and presumably its sentiments – and hung it in the gallery of Somerset Place, the edifice that had been the Protector’s monument to his own glory.

50

Thomas Seymour once said that the memory of brave men lived for ever and that ‘a good name is the embalming of the virtuous to an eternity of love and gratitude among posterity’.

51

To future generations, his good name was lost; but those that had known him still remembered him fondly. He was a turbulent, troublesome individual, but also a likeable one, and – at the start of 1549 – the man who would come closest to marrying the future Queen Elizabeth. As far as is recorded, no other man ever climbed into bed with England’s virgin queen, or trimmed her clothes and intimately appraised her body. As Elizabeth looked at Thomas’s portrait in the gallery at Somerset Place, she would have been able to reflect upon the man who had so nearly seduced her.

He had been the temptation of Elizabeth Tudor.

*1

Starkey (2000, p. 76), referring to Latimer, notes that ‘kicking a man when he is down, still more when he is dead, is something that even the worst of us revolt from’.

*2

Robinson (pp. 278–9). Elizabeth’s co-religionist Jane Grey, when presented with some tinsel, cloth of gold and velvet as a gift from Princess Mary – who loved fine and showy clothes – had even declared that she would not wear it, since ‘that were a shame to follow My Lady Mary against God’s word and leave My Lady Elizabeth which followeth God’s word’.

*3

In the sixteenth century, the age of majority was sixteen for women and twenty-one for men (McIntosh, p. 128).

*4

The younger Harington (1561–1612), who was born to his father’s second wife, was a godson of Elizabeth I. He achieved fame, and some notoriety, for diverse achievements, including his translation of Ariosto’s

Orlando Furioso

and his design for England’s first flushing lavatory.

~

We hope you enjoyed this book.

Elizabeth Norton’s next book,

The Lives of Tudor Women

, is coming in Autumn 2016

For more information, click one of the links below:

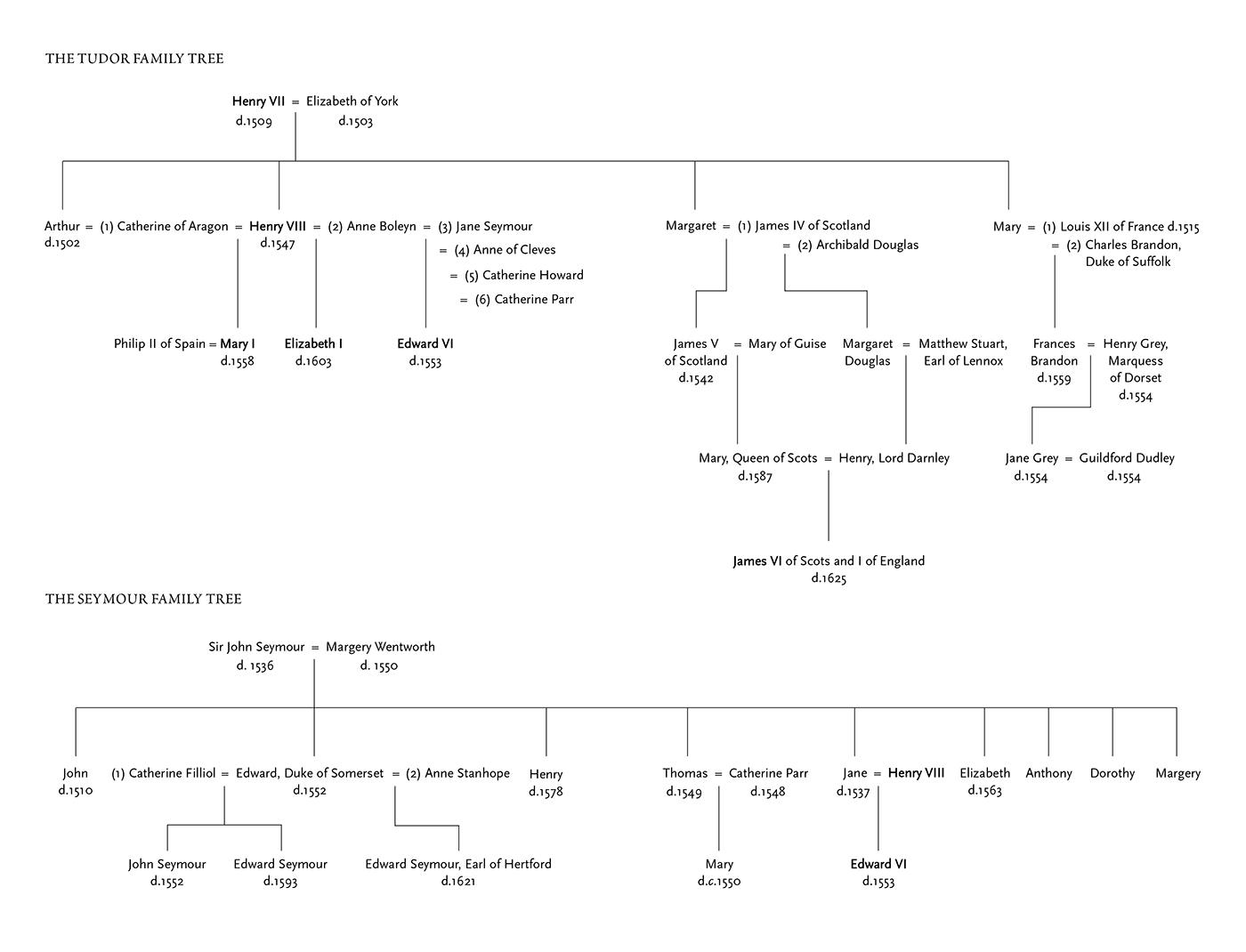

Tudor and Seymour Family Trees

~

An invitation from the publisher

Endpapers, clockwise from top left:

Elizabeth I when Princess,

c.

1546, attributed to Guillaume Scrots

(Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2015; Bridgeman Images)

Sir Thomas Seymour, English School (16th century)

(National Portrait Gallery; Bridgeman Images)

Catherine Parr,

c.

1545, English School

(Universal Images Group; Getty Images)

Edward VI,

c.

1546, attributed to Guillaume Scrots

(Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II; Bridgeman Images)

Sir Edward Seymour by Hans Holbein the Younger

(© The Trustees of the Weston Park Foundation; Bridgeman Images)

Sir William Sharington, English School, 16th century

(Lacock Abbey, Wiltshire; National Trust Photographic Library; Bridgeman Images)

Queen Mary I, 1544, by Master John

(© National Portrait Gallery)

Sir Thomas Parry, c.1532–43, by Hans Holbein the Younger

(Royal Collection Trust © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2015)

Full details of the primary and secondary sources referred to in these notes may be found in the Bibliography on page 332. In all quotations from these sources, the spelling has been modernized.

S. Haynes’s

Collection of State Papers… Left by William Cecil

includes printed transcripts of many of the original manuscripts concerning the Seymour scandal held by the Marquess of Salisbury at Hatfield House. Following a comparison of these transcripts with the originals (microfilm versions BL M485/39) it is clear that, with one exception, discussed elsewhere, Haynes made accurate transcripts. For ease of reference, the documents’ page numbers are, in most cases, given below in preference to their manuscript numbers.

The following abbreviations are used below for certain frequently appearing sources.

‘A Journal’

Adams

et al.

(eds), ‘A “Journall” of matters of state…’

APC

Acts of the Privy Council

‘Certain Brief Notes’

Adams

et al.

(eds), ‘Certayne Brife Notes…’

CSP Domestic

Calendar of State Papers, Domestic…

CSP Domestic (Knighton)

Calendar of State Papers, Domestic… 1547–1553

CSP Foreign

Calendar of State Papers, Foreign

CSP Spanish

Calendar of Letters… Between England and Spain

HMC

Historic Manuscripts Commission

L&P

Letters and Papers… of the Reign of Henry VIII

ODNB

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

VCH

Victoria Country History

series

Prologue: 6 February 1559

1.

Journal of the House of Commons

, 6 February 1559.

2. J. Hayward (1840), pp. 30–2.

3. Elizabeth’s coronation portrait at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG 5175) shows the queen with a significant resemblance to Henry VIII.

4.

Journal of the House of Commons

, 4 February 1559.

5. Ibid., 23–30 January 1559.

6. Portrait of Sir Thomas Gargrave (NPG 1928).

7.

History of Parliament

, for Sir Thomas Gargrave.

8. Indeed, as Duncan (p. 35) notes, her half-sister Mary I had appeared similarly unwilling to Parliament when its members petitioned her to marry.

9. Mueller, Levin and Shenk (p. 24) note that the first evidence that Elizabeth was averse to matrimony came in November 1556.

10. Ibid., p. 16: they also see this as a point of metamorphosis for Elizabeth, noting a marked change in her perception of selfhood in her letters during and after the Seymour scandal.