The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy (25 page)

Read The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy Online

Authors: Irvin D. Yalom,Molyn Leszcz

Tags: #Psychology, #General, #Psychotherapy, #Group

Once the group begins, the therapist attends to gatekeeping, especially the prevention of member attrition. Occasionally an individual will have an unsuccessful group experience resulting in premature termination of therapy, which may play some useful function in his or her overall therapy career. For example, failure in or rejection by a group may so unsettle the client as to prime him or her ideally for another therapist. Generally, however, a client who drops out early in the course of the group should be considered a therapeutic failure. Not only does the client fail to receive benefit, but the progress of the remainder of the group is adversely affected. Stability of membership is a sine qua non of successful therapy. If dropouts do occur, the therapist must, except in the case of a closed group (see chapter 10), add new members to maintain the group at its ideal size.

Initially, the clients are strangers to one another and know only the therapist, who is the group’s primary unifying force. The members relate to one another at first through their common relationship with the therapist, and these therapist-client alliances set the stage for the eventual development of group cohesion.

The therapist must recognize and deter any forces that threaten group cohesiveness. Continued tardiness, absences, subgrouping, disruptive extragroup socialization, and scapegoating all threaten the functional integrity of the group and require the intervention of the therapist. Each of these issues will be discussed fully in later chapters. For now, it is necessary only to emphasize the therapist’s responsibility to supra-individual needs. Your first task is to help create a physical entity, a cohesive group. There will be times when you must delay dealing with pressing needs of an individual client, and even times when you will have to remove a member from the group for the good of the other members.

A clinical vignette illustrates some of these points:

• Once I introduced two new members, both women, into an outpatient group. This particular group, with a stable core of four male members, had difficulty keeping women members and two women had dropped out in the previous month. This meeting began inauspiciously for one of the women, whose perfume triggered a sneezing fit in one of the men, who moved his chair away from her and then, while vigorously opening the windows, informed her of his perfume allergy and of the group’s “no perfume” rule.

At this point another member, Mitch, arrived a couple of minutes late and, without even a glance at the two new members, announced, “I need some time today from the group. I was really shook up by the meeting last week. I went home from the group very disturbed by your comments about my being a time hog. I didn’t like those insinuations from any of you, or from you either [addressing me]. Later that evening I had an enormous fight with my wife, who took exception to my reading a medical journal [Mitch was a physician] at the dinner table, and we haven’t been speaking since.”

Now this particular opening is a good beginning for most group meetings. It had many things going for it. The client stated that he wanted some time. (The more members who come to the group asking for time and eager to work, the more energized a meeting will be.) Also, he wanted to work on issues that had been raised in the previous week’s meeting. (As a general rule the more group members work on themes continually from meeting to meeting, the more powerful the group becomes.) Furthermore, he began the meeting by attacking the therapist—and that was a good thing. This group had been treating me much too gently. Mitch’s attack, though uncomfortable, was, I felt certain, going to produce important group work.

Thus I had many different options in the meeting, but there was one task to which I had to award highest priority: maintaining the functional integrity of the group. I had introduced two female members into a group that had had some difficulty retaining women. And how had the members of the group responded? Not well! They had virtually disenfranchised the new members. After the sneezing incident, Mitch had not even acknowledged their presence and had launched into an opening gambit—that, though personally important, systematically excluded the new women by its reference to the previous meeting.

It was important, then, for me to find a way to address this task and, if possible, also to address the issues Mitch had raised. In chapter 2, I offered the basic principle that therapy should strive to turn all issues into here-and-now issues. It would have been folly to deal explicitly with Mitch’s fight with his wife. The data that Mitch would have given about his wife would have been biased and he might well have “yes, but” the group to death.

Fortunately, however, there

was

a way to tackle both issues at once. Mitch’s treatment of the two women in the group bore many similarities to his treatment of his wife at the dinner table. He had been as insensitive to their presence and their particular needs as to his wife’s. In fact, it was precisely about his insensitivity that the group had confronted him the previous meeting.

Therefore, about a half hour into the meeting, I pried Mitch’s attention away from his wife and last week’s session by saying, “Mitch, I wonder what hunches you have about how our two new members are feeling in the group today?”

This inquiry led Mitch into the general issue of empathy and his inability or unwillingness in many situations to enter the experiential world of the other. Fortunately, this tactic not only turned the other group members’ attention to the way they all had ignored the two new women, but also helped Mitch work effectively on his core problem: his failure to recognize and appreciate the needs and wishes of others. Even if it were not possible to address some of Mitch’s central issues, I still would have opted to attend to the integration of the new members. Physical survival of the group must take precedence over other tasks.

CULTURE BUILDING

Once the group is a physical reality, the therapist’s energy must be directed toward shaping it into a therapeutic social system. An unwritten code of behavioral rules or

norms

must be established that will guide the interaction of the group. And what are the desirable norms for a therapeutic group? They follow logically from the discussion of the therapeutic factors.

Consider for a moment the therapeutic factors outlined in the first four chapters: acceptance and support, universality, advice, interpersonal learning, altruism, and hope—who provides these? Obviously, the other members of the group! Thus, to a large extent,

it is the group that is the agent of change.

Herein lies a crucial difference in the basic roles of the individual therapist and the group therapist. In the individual format, the therapist functions as the solely designated direct agent of change. The group therapist functions far more indirectly. In other words,

if it is the group members who, in their interaction, set into motion the many therapeutic factors, then it is the group therapist’s task to create a group culture maximally conducive to effective group interaction.

The game of chess provides a useful analogy. Expert players do not, at the beginning of the game, strive for checkmate or outright capture of a piece, but instead aim at obtaining strategic squares on the board, thereby increasing the power of each of their pieces. In so doing, players are

indirectly

moving toward success since, as the game proceeds, this superior strategic position will favor an effective attack and ultimate material gain. So, too, the group therapist methodically builds a culture that will ultimately exert great therapeutic strength.

A jazz pianist, a member of one of my groups, once commented on the role of the leader by reflecting that very early in his musical career, he deeply admired the great instrumental virtuosos. It was only much later that he grew to understand that the truly great jazz musicians were those who knew how to augment the sound of others, how to be quiet, how to enhance the functioning of the entire ensemble.

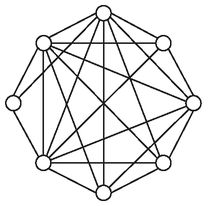

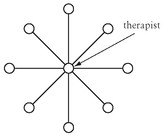

It is obvious that the therapy group has norms that radically depart from the rules, or etiquette, of typical social intercourse. Unlike almost any other kind of group, the members must feel free to comment on the immediate feelings they experience toward the group, the other members, and the therapist. Honesty and spontaneity of expression must be encouraged in the group. If the group is to develop into a true social microcosm, members must interact freely. In schematic form, the pathways of interaction should appear like the first rather than the second diagram, in which communications are primarily to or through the therapist.

Other desirable norms include active involvement in the group, nonjudgmental acceptance of others, extensive self-disclosure, desire for self-understanding, and an eagerness to change current modes of behavior. Norms may be a

prescription for

as well as a

proscription against

certain types of behavior. Norms may be implicit as well as explicit. In fact, the members of a group cannot generally consciously elaborate the norms of the group. Thus, to learn the norms of a group, the researcher is ill advised to ask the members for a list of these unwritten rules. A far better approach is to present the members with a list of behaviors and ask them to indicate which are appropriate and which inappropriate in the group.

Norms invariably evolve in every type of group—social, professional, and therapeutic.

1

By no means is it inevitable that a therapeutic group will evolve norms that facilitate the therapeutic process. Systematic observation of therapy groups reveals that many are encumbered with crippling norms. A group may, for example, so value hostile catharsis that positive sentiments are eschewed; a group may develop a “take turns” format in which the members sequentially describe their problems to the group; or a group may have norms that do not permit members to question or challenge the therapist. Shortly I will discuss some specific norms that hamper or facilitate therapy, but first I will consider how norms come into being.

The Construction of Norms

Norms of a group are constructed both from expectations of the members for their group and from the explicit and implicit directions of the leader and more influential members. If the members’ expectations are not firm, then the leader has even more opportunity to design a group culture that, in his or her view, will be optimally therapeutic. The group leader’s statements to the group play a powerful, though usually implicit, role in determining the norms established in the group.† In one study, researchers observed that when the leader made a comment following closely after a particular member’s actions, that member became a center of attention in the group and often assumed a major role in future meetings. Furthermore, the relative infrequency of the leader’s comments augmented the strength of his or her interventions.

2

Researchers studying intensive experiential training groups for group therapists also concluded that leaders who modeled warmth and technical expertise more often had positive outcomes: members of their groups achieved greater self-confidence and greater awareness of both group dynamics and the role of the leader.

3

In general, leaders who set norms of increased engagement and decreased conflict have better clinical outcomes.

4

By discussing the leader as norm-shaper, I am not proposing a new or contrived role for the therapist. Wittingly or unwittingly, the leader

always

shapes the norms of the group and must be aware of this function. Just as one cannot not communicate, the leader

cannot not influence norms;

virtually all of his or her early group behavior is influential. Moreover, what one does

not

do is often as important as what one does do.