The Thief of Venice (15 page)

Read The Thief of Venice Online

Authors: Jane Langton

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

Her pictures were not sharp and the colors were poor, but Ursula liked them. She leaned against Mary and beamed at the glossy photograph of pigeons eating from her hand in Piazza San Marco.

Her grandmother flipped through them quickly, looking for the picture of herself. "It isn't here," she said, disappointed.

"Oh, there are more." Mary went to look for her second-best collection. Again she couldn't find it. She couldn't find the negatives. Where the hell were they? "I'm sorry, Dorothea," she said, coming back empty-handed. "I'll take another right now if you like."

Mrs. Wellesley went off to arrange her hair, and Mary showed Ursula an out-of-focus shot of a church blanketed in white marble statuary. "Do you know which one this is? I've got them all mixed up." Ursula shook her head. "Oh, well, I'll ask your father. He'll know right away."

*31*

Next day Homer told Mary in confidence about Sam's ghastly trouble—the theft of a couple of relics and the smashing of the borrowed reliquary. "The poor man doesn't know what to do. He's beside himself."

"Well, no wonder. How terrible! Who could have done such a thing? "

"Who knows? Somebody must have a key." Homer sank his voice to a whisper. "Sam suspects his mother-in-law. She's Savonarola in reverse."

"You mean—?"

"Instead of burning vanities like fancy clothes and jewelry, she'd like to burn the Bible."

"I see." Mary laughed. "Look, why don't we take him out to dinner? I'll bring along my pictures, and he can tell me which is which."

Every day the high water was worse. The meteorologist reporting for the local TV station in the Palazzo Labia talked excitedly about the dire results of bureaucratic delay in dealing with

acqua alta

. "One!"—he held up his left hand and raised his ringers one at a time—"the delay in raising the level of the pavement in

Piazza

San Marco. Two! the delay in constructing mobile barriers and reinforcing the jetties at the three entrances to the lagoon. Three! the delay in completing the dredging of silt from the canals to speed up the flushing of high water. Four! the delay in preventing pollution from the passage of tankers within the island barrier. Five! the delay in preventing the discharge of pollutants from the mainland." The meteorologist gave up on his fingers as a large map appeared behind him. It was alive with arrows running northward in the Adriatic, pointing directly at the city of Venice. The arrows were the violent winds resulting from a steep drop in atmospheric pressure.

The wind was real. Homer, Mary, and Sam were blown sideways as they splashed to the San Zaccaria stop on the Riva through a retreating slop of water, and took the next vaporetto up the Grand Canal. At Ca' Rezzonico there was a famous restaurant with a garden. They sat under a leafy trellis and ordered what Sam recommended,

malfatti alia panna

and

scampi fritti

. Sam himself ordered a plate of squid cooked in its own black ink.

While they were waiting, Mary took out her photographs. "Oh, Sam, forgive me, these are just typical tourist pictures, but perhaps you can identify the ones I can't remember. This one, for instance." She shoved a photograph of an imposing doorway under his nose.

Sam gave it a glance while the waiter set down their plates, and then he snatched it up and looked at it again. "What's this?"

"I don't know." Mary took it from him and showed it to Homer. "That's why I'm asking you. It's a church somewhere, but I don't know which one. Do you know, Homer?"

"God, how should I know?" said Homer, who was still steeped in ignorance, except of course about the Aldine

Dream of Poliphilius

and the illuminated

Vitruvius

of Cardinal Bessarion, and other ancient works.

Sam took the picture back and said softly, "It's Lucia. I swear it's Lucia."

"Lucia?"

"This woman walking in front of the church. It's Lucia Costanza. The new procurator of San Marco. You remember, Homer. I told you about her."

"Oh, right," said Homer, taking an interest at once. "I read about her in the

New York Times

before we came. She's the one who's supposed to have killed her husband, only you swear she didn't."

"Because she disappeared," exclaimed Mary, putting two and two together. "Isn't she the woman the carabinieri are looking for? The one who vanished when her husband was murdered?"

Sam gazed at Mary's picture. "She's alive, she's here. She's somewhere here in Venice." He threw back his napkin and stood up. "When was this? When did you take this picture? Where were you?"

"Oh, Sam, I'm terribly sorry. I haven't the faintest idea where I was."

Sam pawed at the back of his chair and pulled on his coat. "I'll look for it. I'll look until I find it."

Mary groped under the table for her bag. "Books, Sam, we can look for it in books. I've got a really good guidebook. It's chock-full of churches."

"You mean we're leaving?" Homer looked with dismay at his dinner, for which he was about to pay forty thousand lire.

In a far corner of the same restaurant Doctor Richard Henchard was having dinner. Turning his head, he saw Mary Kelly in the company of two men. One was familiar to him. At once he shifted his chair behind the trunk of a climbing vine. Turning up the collar of his jacket, he shivered and said to his dinner partner,

"Hofreddo. E lei? Non trova chefaccia un po' freddo?"

The pretty nurse with whom he was dining was new in his surgery, a clumsy girl with a habit of dropping instruments into abdominal cavities. In answer to his question she shook her head and went on with her story about the Virgin's veil.

"Haven't you heard? It's so exciting. They've found a piece of the blue veil of the Virgin Mary. It's on display in the Church of Santo Spirito. Of course"—the nurse didn't want to seem old-fashioned, because, after all, Riccardo was a scientist—"one doesn't know whether to believe it or not, but they say it's already cured a crippled child." The nurse gazed at Henchard worshipfully. "What do you think, Riccardo?" Oh, God, he had such magnificent eyes, with the most adorable little wrinkles at the corners. In addressing her he was still using the formal "lei." The pretty nurse hoped for an impassioned "tu" before the evening was over.

She hoped in vain. Henchard had another conquest in mind. Not tonight, but soon, very soon.

*32*

They couldn't find it, the place where Lucia Costanza was striding so purposefully across Mary's photograph from right to left. The church facade in the background refused to be identified.

Mary looked for it in her guidebooks. Sam ransacked his shelves for textbooks on Venetian architecture. He borrowed Dorothea's big coffee-table book,

Venice, City of Enchantment

, which was packed with huge color photographs of the Ducal Palace, San Marco, the crowds in the piazza, gondolas against the sunset, the masked revelers of carnival time, the costumed rowers of the Regata Storica. The church they were looking for was not to be found.

Next day Sam fell ill. He set out early in the morning two hours before his first appointment in the Marciana to look at obscure churches in the unvisited neighborhood north of the public gardens. It was one of the many places where Mary had lost her way.

"I took pictures just the same," she told Sam, "even when I didn't know where I was. I wandered all over the place in Sant' Elena beyond the Giardini, and I was really mixed up between the Zattere and the Rio Nuovo."

The

sestiere

called Sant' Elena was one of the higher regions of the city. There was little evidence of high water, but before Sam had been out of the house five minutes on his way along the Riva to the Giardini, he felt so faint he had to turn around and go back.

He locked himself in his study, dropped heavily on the bed, and turned his face away from the sight of the vandalized reliquary on the table.

At once the usual scene began to play in his head.

A courtyard with statuary, a staircase, a woman on the stairs, an office, a window overlooking another courtyard, the woman walking quickly in front of him and sitting down, his own hands on her desk, his voice and her laughter. Where was she?

She was not far away. Dottoressa Lucia Costanza had not fled to the mainland to conceal herself somewhere in the Veneto. It had never occurred to Lucia to lose herself in some crowded metropolis like New York or London or even in the city of Rome. She was serenely convinced that the crime of her husband's murder would sooner or later be solved, and then she could come out of hiding and reorganize her life and resume her interrupted career.

Her attempt at renting an apartment, that simple little place near the Casa del Tintoretto, had been cut short by the man who had turned up on the doorstep claiming to have an earlier lease.

The apartment hadn't been worth fighting for anyway. It was dingy, and serious repairs would have been required to fix the closet wall. Lucia had given up at once, deciding to take a chance on the loan of a place in Cannaregio belonging to an old school friend, now working in America. She had nearly forgotten the key the friend had thrust upon her, but now she extracted it gratefully from her bag and settled in.

She had begun to recover from the fearful shock of learning from newspaper headlines that her poor unhappy husband had been killed and that she herself was under suspicion. At first she couldn't believe it. Leaving Lorenzo Costanza had been such an ordinary thing, painful but ordinary, the long-overdue act of a perfectly ordinary aggrieved wife. And it hadn't been easy. It had taken courage to abandon her home and begin a new life. It had been like amputating a diseased part of her body in order to save the rest. She had felt lopped and chopped.

That had been bad enough, but the rest was a nightmare. Poor Lorenzo was dead! Of course she had long since lost all respect for her husband, but she would not have wished his life to be so violently cut short. And she couldn't get used to the fact that she was now the object of

una caccia all' uomo

, a manhunt. It sickened Lucia to read the details of the lurid case against her.

"The old, old story! SHE was ambitious, HE was a man with a poetic nature."

If the revelations in the paper hadn't been so persuasive and threatening, she would have laughed.

She was grateful that the only picture they had found was a snapshot of a solemn thirteen-year-old with braces on her teeth, taken long ago at the school of the Suore Canossiane in Murano. It had been taken under duress—

"Ma, cam Lucia, tutti devono avere una fotografia!"

"O, Suora, non to, perfavore!"

But of course they had insisted. After that, she had always resisted and refused and ducked her head and turned her back, and destroyed any pictures that turned up, because in photographs she always looked so ugly. Her nose looked even bigger than it was, and her neck too long and thin.

So the image of the gawky pigtailed kid with braces on her teeth was the only one left. It looked ridiculous next to the story about some terrible woman who had killed her husband and run away. But it wasn't funny, not really. The hideously incriminating account had appeared not only in the local papers but in the national dailies,

Corriere della Sera

and

La Repubblica

. It meant walking away from her splendid new position as a procurator of San Marco, it meant unpinning her thick, too-curly hair and letting it fall around her face, it meant hiding herself away in this small square and becoming a person known as Signora Sofia Alberti.

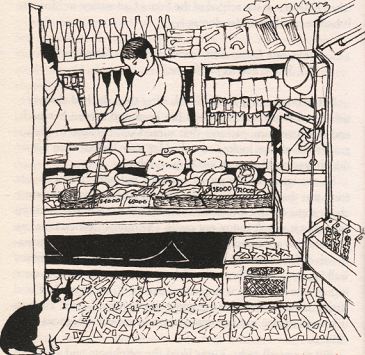

But it was all right. Lucia liked the neighbors and she liked the square. Every day she shopped in the alimentari of young Stefano, who teased her—

"Signora Sofia Alberti? No, no! Sofia Loren!"

For fresh fruits and vegetables there was a little

negozio

presided over by a kindly old woman.

"Questa, cara mia?"

she would say, picking out the finest head of lettuce, chattering about her grandchildren as she twisted the corners of the wrapping paper. In the square Lucia admired the fat babies and chatted with their mothers. She knew the names of all the little boys riding tricycles and bouncing footballs against the trees in the middle of the square.

Sometimes she held one end of a skipping rope while a grandmother held the other for two little girls who jumped and tangled their feet and hopped happily up and down. She showed them how to skip in a dancing step, right foot forward, left foot back.

She taught them to make paper boats like cocked hats, and drop them from one side of the bridge over the Rio de la Misericordia. "You see? It's like a race. They float under the bridge and come out on the other side, so if every boat has a name, you'll know who wins."

They were overjoyed. They scribbled their names with crayon. "Yes, yes," cried Guido, "look at mine!"

"

Anna

, mine's

Anna

!"

"Look, look, mine's

Regina

!"

"Oh, signora, write your name too! Your boat will be

Sofia

!"