The Third Reich at War (38 page)

These mass murders and pogroms often took place in public, and were not only observed and reported by participants and onlookers, but also photographed. Soldiers and SS men kept snapshots of executions and shootings in their wallets and sent them home to their families and friends, or took them back to Germany when they went on leave. Many such photos were found on German troops killed or captured by the Red Army. The soldiers thought that these reports and photos would show how German justice was meted out to a barbaric and subhuman enemy. The Jewish population seemed to confirm everything they had read in Julius Streicher’s antisemitic tabloid paper

The Stormer

: everywhere the soldiers went in Eastern Europe they found ‘filthy holes’ swarming with ‘vermin’, ‘dirt and dilapidation’, inhabited by ‘unending quantities of Jews, these repulsive

Stormer

types’.

32

In the southern sector of the front, Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt found himself confronted with quarters that he roundly condemned as a ‘filthy Jewish hole’.

33

‘Everything is in a condition of horrifying dilapidation,’ wrote General Gotthard Heinrici to his wife on 11 July 1941. ‘We are learning to treasure the blessings of Bolshevik culture. The furnishings are only of the most primitive kind. We are living mostly in empty rooms. The Star of David is painted all over the walls and blankets.’

34

Heinrici’s casual equation of dirt, Bolshevism and ‘the Star of David’ was typical. It informed the actions of many officers and men of all ranks in the course of the eastern campaign.

III

On 16 July 1941, speaking to Göring, Lammers, Rosenberg and Keitel, Hitler declared that it was necessary ‘to shoot dead anyone who even looks askance’ in order to pacify the occupied areas:

35

‘All necessary measures - shooting, deportation etc. - we will do anyway . . . The Russians have now given out the order for a partisan war behind our front. This partisan war again has its advantage: it gives us the possibility of exterminating anything opposing us.’ Foremost amongst those opponents of course, in Hitler’s mind, were the Jews, and not just in Russia but also in the rest of Europe, indeed the rest of the world. The following day he issued two new decrees on the administration of the newly conquered territories in the east, giving Himmler complete control over ‘security measures’ including, it went without saying, the removal of the threat of ‘Jewish-Bolshevik subversion’. Himmler understood this to mean clearing all the Jews from these areas by a mixture of shooting and ghettoization. From his point of view, this would pave the way for the further implementation of his ambitious plans for the racial reordering of Eastern Europe, as well, of course, as vastly increasing his own power in relation to that of the nominally responsible administrative head of the region, Alfred Rosenberg. He ordered two SS cavalry brigades to the region, numbering nearly 13,000 men, on 19 and 22 July 1941 respectively.

36

On 28 July 1941 Himmler issued guidelines to the First SS Cavalry Brigade to assist them in their task of dealing with the inhabitants of the vast Pripet marshes:

If the population, looked at in national terms, is hostile, racially and humanly inferior, or even, as will often be the case in marshy areas, composed of criminals who have settled there, then everyone who is suspected of supporting the partisans is to be shot; women and children are to be taken away, livestock and foodstuffs are to be confiscated and brought to safety. The villages are to be burned to the ground.

37

It was understood from the outset that the partisans were inspired by ‘Jewish Bolshevists’ and that therefore a major task of the cavalry brigades was the killing of the Jews in the area. On 30 July 1941 the First SS Cavalry Brigade noted at the end of a report: ‘In addition, up to the end of the period covered by this report, 800 Jewish men and women from the ages of 16 to 60 were shot for encouraging Bolshevism and Bolshevik irregulars.’

38

The extension of the killing from Jewish men to Jewish women and children as well ratcheted up the murder rate to new heights. The scale of the massacres carried out by the newly assigned SS cavalry brigades in particular was unprecedented. Under the command of the Higher SS and Police Leader for Central Russia, Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski, one brigade shot more than 25,000 Jews in under a month, following an order issued at the beginning of August by Himmler, who was visiting the area, that ‘all Jewish men must be shot. Drive Jewish women into the marshes.’ Women were no longer to be spared, in other words, they were to be drowned in the Pripet marshes. Yet, as the SS cavalry reported on 12 August 1941: ‘Driving women and children into marshes did not have the success it was meant to, since the marshes were not deep enough for them to sink in. In most cases one encountered firm ground (probably sand) below a depth of 1 metre, so that sinking-in was not possible.’

39

If it was not possible to drive Jewish women into the Pripet marshes, then, SS officers concluded, they too had to be shot. Already in the first half of August, Arthur Nebe, the commander of Task Force B, which operated in Bach-Zelewski’s area, ordered his troops to start shooting women and children as well as men. Further south, Himmler’s other SS brigade, under the command of Friedrich Jeckeln, began the systematic shooting of the entire Jewish population, killing 23,600 men, women and children in Kamenetsk-Podolsk in three days at the end of August 1941. On 29 and 30 September 1941, Jeckeln’s men, assisted by Ukrainian police units, took a large number of Jews out of Kiev, where they had been told to assemble for resettlement, to the ravine of Babi Yar, where they were made to undress. As Kurt Werner, a member of the unit ordered to carry out the killings, later testified:

The Jews had to lie face down on the earth by the ravine walls. There were three groups of marksmen down at the bottom of the ravine, each made up of about twelve men. Groups of Jews were sent down to each of these execution squads simultaneously. Each successive group of Jews had to lie down on top of the bodies of those that had already been shot. The marksmen stood behind the Jews and killed them with a shot in the neck. I still recall today the complete terror of the Jews when they first caught sight of the bodies as they reached the top edge of the ravine. Many Jews cried out in terror. It’s almost impossible to imagine what nerves of steel it took to carry out that dirty work down there. It was horrible . . . I had to spend the whole morning down in the ravine. For some of the time I had to shoot continuously.

40

In two days, as Task Force C reported on 2 October 1941, the unit killed a total of 33,771 Jews in the ravine.

41

By the end of October, Jeckeln’s troops had shot more than 100,000 Jewish men, women and children. Elsewhere behind the Eastern Front, the Task Forces and associated units also began to kill women and children as well as men, starting at various times from late July to early September.

42

In all these cases, the few men who refused to take part in the murders were allowed time out without any disciplinary consequences for themselves. This included even quite senior officers, for example the head of Task Unit 5 of Task Force C, Erwin Schulz. On being told at the beginning of August 1941 that Himmler had ordered all Jews not engaged in forced labour to be shot, Schulz requested an interview with the head of personnel at the Reich Security Head Office, who, after hearing Schulz’s objections to participating in the action, persuaded Heydrich to relieve the reluctant officer of his duties and return him to his old post at the Berlin Police Academy without any disadvantage to his career. The great majority of officers and men took part willingly, however, and raised no objections. Deep-seated antisemitism mingled with the desire not to appear weak and a variety of other motives, not the least of which was greed, for, as in Babi Yar, the victims’ possessions in all these massacres were looted, their houses ransacked, and their property confiscated. Plunder, as a police official involved in the murders later admitted, was to be had for all.

43

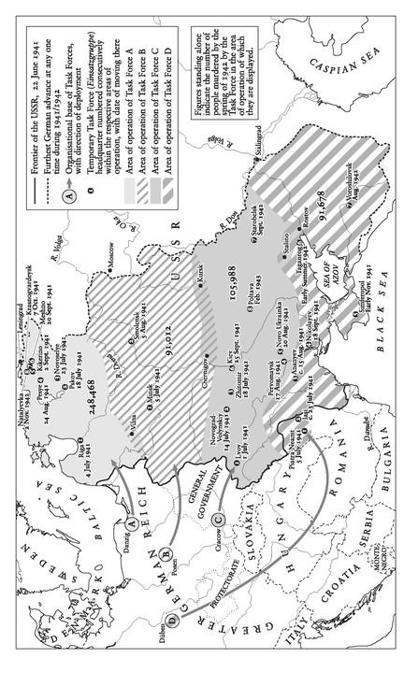

10. Killing Operations of the SS Task Forces, 1941-3

In the town of Stanislaw’w in Galicia, Hans Kr̈ger, the head of the Security Police, was informed by the local German authorities that the ghetto they were about to set up was not going to be able to house anything like the entirety of the town’s Jewish population, which numbered around 30,000, possibly more. So he rounded up the town’s Jews on 12 October 1941 and lined them up in a long queue that reached to the edge of prepared open ditches in the town cemetery. Here they were shot by German police, ethnic Germans and nationalist Ukrainians, for whom Kr̈ger provided a table laden with food and alcoholic spirits in the intervals between the shootings. As Kr̈ger oversaw the massacre, striding round with a bottle of vodka in one hand and a hot-dog in the other, the Jews began to panic. Whole families jumped into the ditches, where they were shot or buried by bodies falling on top of them; others were shot as they attempted to climb the graveyard walls. By sunset, between 10,000 and 12,000 Jews, men, women and children, had been killed. Kr̈ger then announced to the remainder that Hitler had postponed their execution. More were trampled in the rush to the cemetery gates, where they were again rounded up and taken to the ghetto.

44

In some cases, as in the town of Zloczo’w, local German army commanders protested and managed to get the murders stopped, at least temporarily.

45

By contrast, in the village of Byelaya Tserkow, south of Kiev, the Austrian field commander, Colonel Riedl, had the entire Jewish population registered and ordered a unit of Task Force C to shoot them all. Together with Ukrainian militiamen and a platoon of soldiers from the Armed SS, the Task Force troops took several hundred Jewish men and women out to a nearby firing range and shot them in the head. A number of the victims’ children were taken in lorries to the firing range shortly afterwards, on 19 August 1941, and shot as well, but ninety of the youngest, from small babies up to six-year-olds, were kept behind, unsupervised, in a building on the outskirts of the village, without food or water. German soldiers heard them crying and whimpering through the night, and alerted their unit’s Catholic military chaplain, who found the children desperate for water, lying around in filthy conditions, covered in flies, with excrement all over the floor. A few armed Ukrainian guards stood about outside, but German soldiers were free to come and go as they pleased. The chaplain enlisted the aid of a regimental staff officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Helmuth Groscurth, who, after inspecting the building, posted soldiers round it to prevent the children being taken away. Outraged at his authority being overridden, Riedl protested to the regional commanding officer, Field Marshal von Reichenau, that Groscurth and the chaplain were departing from proper National Socialist ideology. ‘He explained,’ Groscurth reported, ‘that he held the extermination of the Jewish women and children to be urgently required.’ Reichenau backed Riedl and ordered the children’s murder to go ahead. On 22 August 1941 the children and infants were taken out to a nearby wood and shot on the edge of a large ditch dug in preparation by Riedl’s troops. The SS officer in charge, August Häfner, later reported that, after objecting that his own men, many of whom had children themselves, could not reasonably be asked to carry out the shootings, he obtained permission to get Ukrainian militiamen to do the deed instead. The children’s ‘wailing’, he recalled, ‘was indescribable. I shall never forget the scene throughout my life. I find it very hard to bear. I particularly remember a small fair-haired girl who took me by the hand. She too was shot later . . . Many children were hit four or five times before they died.’

46

Groscurth’s horror at these events reflected the moral doubts that had led him to take up contacts with the conservative-military resistance. He protested that such atrocities in effect were no better than those committed by Soviet Communists. Reports of the events in the village were bound to reach home, he thought, damaging the standing of the German army and causing problems for morale. A devout Protestant and conservative nationalist, his courageous stand in August 1941 earned the wrath of his superiors, and he was duly reprimanded by Reichenau. To some extent he may well have phrased his objections in such a way as to make them count with his superiors. Yet his report to Reichenau on 21 August 1941 concluded that the outrage lay not in the shooting of the children but in the fact that they were left in appalling conditions while the responsible SS officers dithered. Once the decision had been made to kill the adults, he saw no option but to kill the children as well. ‘Both infants and children,’ he declared, ‘should have been eliminated immediately in order to have avoided this inhuman agony.’

47