The Time by the Sea (10 page)

Read The Time by the Sea Online

Authors: Dr Ronald Blythe

Forster’s clothes were a miracle of drabness, I used to wonder where one could buy them. They were so careful in having nothing to say. But his talk! Imo’s talk. How can I recall her sentences but not his? The lopsided ness of life.

Imogen’s flat looked out on the High Street and towards the sea. The floor was covered with fresh coconut matting and a design for Honegger’s

King David

by Kokoschka hung on the wall. Seagulls would skirmish on the windowsills. Neat copy fluttered all over everything. Once when I went to Dartington they let me have her room which was uncannily similar to the Aldeburgh flat. There they spoke of her with

love-struck

awe, and with still a kind of mourning at her going. And I too was made aware of the wealth and comfort which she abandoned in 1951 for what at first was a virtual homelessness and a suitcase. Also a desert from a throne – not that this would have occurred to her. When we met in 1955 these losses had been

sensibly

replaced by her knowing the total dependency which Britten, the greatest English composer of the twentieth century, had on her. There was no one else. They were about the same age. They shared a similar

music culture and a similar drive, and in some ways they were equals.

As the Festival spread through the town, engulfing the Jubilee Hall, the Parish Church, the Baptist Chapel, the Moot Hall, the hotels and boarding houses, the beach, the very air, there were rumbles. But Imogen had only to walk down the High Street, her eyes fixed on no one or anything, than a kind of armistice ensued. She would ‘look straight past you’ but people

understood

. Should someone, not knowing the drill, bring her to a halt she might give them a full minute of her time. But no one for a minute thought that she was stuck up. Miss Holst had better things to do than

gossip

. She had no idea that she walked blindly through something approaching adoration, nor would it have pleased her to know it.

I would tell her about the circle at the far end of the town, the artists Juliet Laden and Peggy Somerville, and the writers who were often with me, and Imogen would say, ‘But don’t they like our Festival? – some do not.’ And I would say, ‘They don’t know it is ours.’ Which was true if strange. There was another

Aldeburgh

, another Suffolk. Some thought that the Festival was wearing me out and some that the shoemaker should stick to his lathe and just write. Their concern made me feel pleasantly hard done by. But the

contrasting

venues of Crag House and Brudenell House created a drama in my life, whilst the ancient basic Aldeburgh

of the fishermen enthralled me, it being so remote. I remember attempting to emulate Imogen’s indifference to accommodation, but this was impossible. And to both her and Christine Nash’s incomprehension I spent a lot of time making ‘a nest’. Their word.

Sometimes Ben would drop me off after a Festival meeting in his Rolls, and all at once I would feel troubled and lonely. Unsure of myself and ‘far from home’. Although the question was, ‘Where was home?’ And where should I be going? And, maybe, who with? When Imogen knocked on my door with a Cragg Sisters’ cake, it would be ‘Very nice, dear.’ But not looking around. All anyone needed was a chair, a table and a bed. Unless one was Benjamin Britten when a Miss Hudson was essential. I don’t think anyone ‘did’ for Imogen. She adored food and drink but was no cook. I was openly hungry half the time like a dog.

Imogen said in her diary:

When I went down the stairs Ben was putting his shoes on to walk uphill with me – he said wouldn’t I stay but I said no and then when he got to the door he looked so depressed that I said yes. So we had a drink … so we drank to wealth and he said ‘Good old Peter Grimes’ and we laughed a lot and he said he hoped I wouldn’t think that life at Aldeburgh was

always

like this so I assured him it was nothing after life at Dartington.

But it was. On this occasion, ‘Miss Hudson had cooked a superb meal and we both felt better.’

Rehearsing on the Crag Path in the evening I would fetch fish and chips and we would sit on the wall in a line to eat them. But the real feed was in Juliet’s limitless kitchen at Brudenell House. Or a similar meal at Peggy Somerville’s limited table.

Imogen died early on a March morning in 1984. Might she have a sip of water – like a bird? After which ‘her head drooped gently sideways … and she slipped away’. I watched her funeral procession to where Ben lay in Aldeburgh churchyard on local tele vision. A

handful

of friends sang the five-part

Sanctus

by Clemens non Papa, a canon she had taught them, at her open grave. The last time I saw it, pointed sycamore leaves had covered it.

On 29 September 1952, her first day as an Aldeburgh inhabitant, she wrote in her diary:

Ben asked me in after a choir practice of

Timon of Athens

. We were talking about old age and he said that nothing could be done about it, and that he had a very strong feeling that people died at the right moment, and that the greatness of a person included the time when he was born and the time he endured, but that this was difficult to understand.

THE SAYINGS OF IMOGEN

He was spared the nineteenth-century craving for originality at any price.

It would be fairly safe to guess that the first tune he ever heard was a hymn tune.

In the prolonged hush before the expected ‘

resurrection

of the dead’ the harmonies move through remote regions that had never before been explored. And in the final ‘grant us thy peace’, the piercing notes of the trumpets mount higher and higher to their climax of gratitude.

This talk is concerned with the editor’s need for second thoughts; with the sight-reader’s struggles to disregard most of what is on the printed page; with the composer’s exasperation at having to fight against the publisher’s house rules, with the learner’s lack of definite instruction, the listener’s damaging preference for what he is used to, and with the danger of still believing everything that one has ever been taught.

Looking through the early volumes of the

Journal of the Folk-Song Society

we can almost hear the ‘twiddles and bleating ornaments’ of Mr Joseph Taylor, carpenter; and the broad, even notes of Mr George Gouldthorpe, lime-burner, who ‘gave his tunes in all possible gauntness and barenness’; and the ‘pattering, bubbling, jerky, restless and briskly energetic effects’ of Mr George Wray, brickyard-worker and ship’s cook, who had a grand memory at the age of eighty and sang his innumerable verses with a jaunty contentment.

Those who live in the North are used to keeping out the cold by singing with half-closed vowel sounds to prevent the gale-force wind from giving them toothache, and by dancing quick rhythms with all their energy.

Over tea in front of a blazing fire, he [Britten] suddenly said, ‘Did your father get terribly depressed?’ And then before I knew where I was I told him how I’d neglected G [Gustav] during the last 2 years of his life, being ambitious about jobs instead of ruling bar-lines for him, and how it was one more reason why it was lovely to be doing

bar-lines in

Gloriana

. Ben said he’d been quite sure that he’d been responsible for his mother’s death & it had taken ages to realise that he hadn’t been.

Ben will realise that when one is always teaching amateurs and future professionals who are still immature, one needs constantly to be criticised on one’s own music by someone who one knows is a better musician than oneself. Now in South Devon, we had so many blessings but we hadn’t many musicians better than me at that time … I thought I mustn’t get into the habit of this. I remember walking round the garden in early spring and thinking, ‘Now, you could live here for the rest of your life.’ It seemed a kind of heaven on earth, and then thinking, ‘No, because you are a musician, and you have got to go on teaching and got to go on having really strict criticism.’

In 1952 I came to live in Aldeburgh to help with what Britten described as ‘an infinity of things great and small’.

Noye’s Fludde

The first plans were discussed on a long walk over the marshes with the rain streaming down our necks; not long afterwards we were buying china mugs from Mrs Beech in the High Street, to be slung up for the newly invented percussion instrument. I remember the concentration on Britten’s face as he tapped each mug with a wooden spoon.

I must make room to include the blessing of not having to go on buying new clothes when the old ones are not only tougher but are also much more beautiful. For special occasions in the Directors’ Box at the Maltings I’m still wearing the

wool-embroidered

evening jacket I bought for

£

5 in South Kensington in 1928.

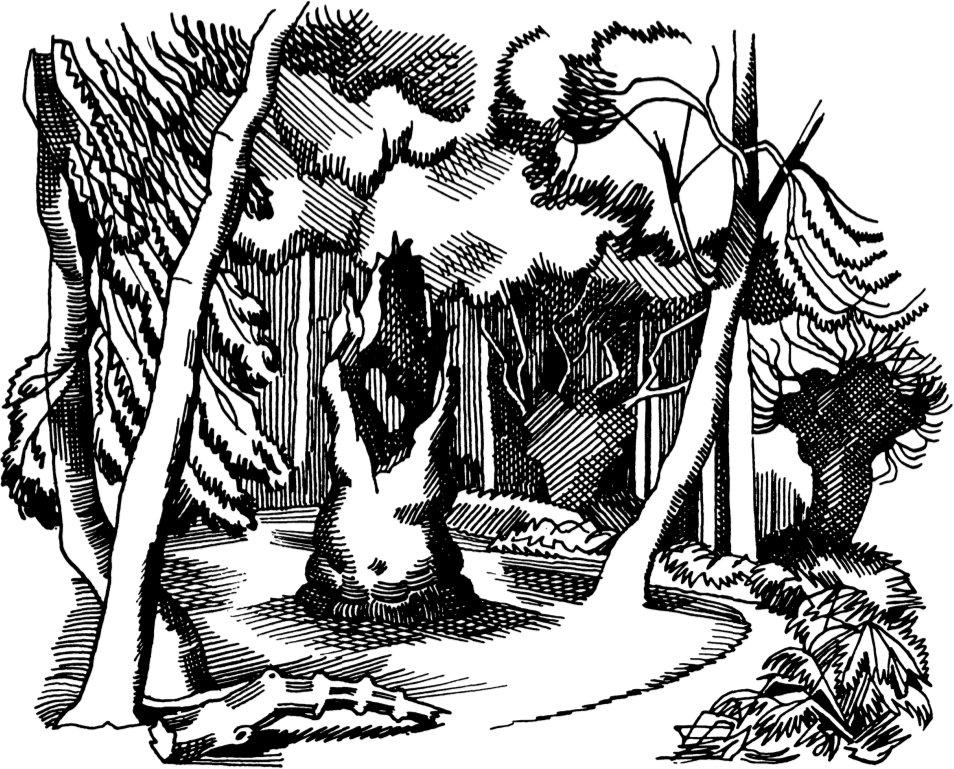

John Nash:

Staverton Thicks

Â

One April morning in 1956 I made one of my planless walks from Slaughden towards Orford and with the usual elated feeling. There would be a wonder midway although I knew nothing of its existence. All I

experienced

at this moment was a tossing about of freedom. The sea was glorious and near at hand, the gulls screamed and the air was intoxicating. At Slaughden the Alde turned into the Ore, and the Aldeburgh Marshes became the Sudbourne Marshes. On the left were the Lantern and King's Marshes. Orford Castle was the obvious destination but like a boy leaving the biggest sweet in the bag until last, I turned right towards Butley. Somebody had told me that Chillesford Church tower was pink because it contained lots of coraline crag. But what drew me would be the stunted oaks and the limited nature of things. And yet at the same time the grandeur of things, for Victorian aristocrats had shot over these acres. So I saw Hansel and Gretel Lodge, and dark entrances to country houses, and signposts to Hollesley where Brendan Behan would be a Borstal Boy. This walk would become a preface to a guidebook as yet unwritten. The poor soil of the Suffolk sandlings had made for skimpy farming

but had provided the next best thing to Scotland for shoots.

Just below it there existed something else. Butley loomed large on my âGeographical' two-miles-to-

the-inch

map. A rivulet wriggled in its direction. And so I came to the Thicks a little way on the right of the Woodbridge road. It would play a large part in my imagination. I took all my friends there, the poet James Turner, John Nash, the Garretts, Richard Mabey. âYes,' said Benjamin Britten, âI know it well.' John Nash had told me that when he was painting he âliked to have a dead tree in the landscape'. Except that Staverton Thicks was not dead, only perpetually dying. And thus everlastingly alive. Although with no apparent struggle. It showed its great age and exposed its ageing, and one flinched from such candour. But why had no one cleared it and replanted it? What had happened? What was happening?

An early friend of John Nash's youthful days was Sidney Schiff, the translator of Proust. Schiff had taken over as translator when Charles Scott Moncrieff died. John Nash gave me the first volume,

Time Regained

, which Schiff had given him. In it Schiff, who wrote under the name of Stephen Hudson, had put, âMy dear John, I want you to have this book. Begin by reading from p. 210 to p. 274. If that means so much to you as I hope, begin at the beginning and read it

slowly

to the end. 30th March '32.'

These sixty or so pages describe a soliloquy on the artistâwriter's life when, arriving late for a concert, he is put into the library until the first work is ended. His memory wanders back to the celebrated

memory-providing

madeleine and, although he is in Paris, to the Normandy coast, and takes in the decision to be either painter or writer. I had just read Sidney Schiff's

instructions

. Fragments of the soliloquy in the Paris library fluttered through my head as I walked towards Orford and penetrated the strange wood. Passages such as âthe large bow-windows wide open to the sun slowly setting on the sea with its wandering ships, I had only to step across the window-frame, hardly higher than my ankle, to be with Albertine and her friends who were walking on the sea-wall' made me think of Juliet Laden and Peggy Somerville softly drawing in pastel the young people below, and how perfect it would be this very evening to be at Brudenell House telling them about my walk. I too was attempting to concentrate my mind on a compelling image, a cloud, a triangle, a belfry, a flower, a pebble. I wondered if I should make the lovers in my half-written novel walk this way. And then, thinking of Denis Garrett and his botanic company, I was startled when Proust includes him in these recommended pages â when the narrator says that his sorrows and joys

had been forming a reserve like albumen in the ovule of a plant. It is from this that the plant

draws its nourishment in order to transform itself into seed at a time when one does not yet know what the embryo of the plant is developing, though chemical phenomena and secret but very active respirations are taking place in it. Thus my life had been lived in constant contact with the elements which would bring about its ripening â¦

The writer envies the painter; he would like to make sketches and notes and, if he does so, he is lost â¦

John Nash sketched through a grid of lines and dotted in here and there âlate afternoon', âbrowning grey', âstill water', as reminders.

According to his youthful armour-bearer it was among the young oaks of Staverton that St Edmund was murdered by the Danes, tied naked to one of the trees and made a target for arrows. This armour-bearer lived, like the trees, to be very old and thus he was able to tell this execution to Athelstan, who told it to Dunstan, who told it to his friend Abbo of Fleury, who sensibly wrote it down.

The Thicks was also the scene of a Tudor picnic, when Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, and his wife, Henry VIII's sister, spread linen in its shade, drank wine, sang songs and ate â what? This story delighted me as a kind of alfresco masque; when I imagined a pretty site a mile or so from the shield-bedecked Augustinian Priory, and some spontaneous desire to

make merry out of doors. But then I looked up the Duke â and what a monster! But a good-looking monster, one of the ânew men' of the Reformation who had gone from strength to strength without losing his head. I see him lying full length on the then thick summer grass, the oaks above as young as he is, and by his side his wife Mary who was once Queen of France. Henry was furious when they married in Paris without his permission, but calmed down when her enormous dowry for the first husband was returned in

instalments

. In Suffolk they called her âthe French queen', not the Duchess. She would have been buried in St Edmundsbury Abbey had not her brother pulled it down. But she can be found in a corner of St Mary's Church near by, the woman who ate â what? â in

Staverton

Thicks.

Hugh Farmer, into whose little wood I stole so long ago, himself describes it in a Festival Programme Book. He lived there and his account of it is incomparable. He tells of his life there in

A Cottage in the Forest

. But it has never been the adjunct of a great house.

The trees consist chiefly of oaks of every

conceivable

shape, although none is of very great height, and of an age estimated at between seven and eight centuries. Many are stag-headed because, until its abolition a century and a half ago, there was a right for local people to top and lop the trees for fuel.

Many of them are hollow and hollies and elder seeds brought by birds have rooted and grown up from the crowns, so that sometimes a tree grows out of a tree ⦠There is a tradition that this is a Druidic grove and at night, when the owls are crying and the gaunt arms of the ancient trees seem outstretched to clutch, this is an eerie place ⦠A remnant of primeval forest. A very ancient plantation to provide the Priory with fuel and timber for building ⦠What does it matter? Staverton Park is probably the oldest living survival in East Anglia, a strange place, history and tradition apart, with a character all its own. On a still midsummer night when the nightjars churn, and the roding woodcock croak overhead, in deep winter when the snow under the hollies is crimsoned by the berries dropped by ravenous birds, or at autumn dusk when the mist rises wraithlike from the stream and the rusty wailing of the stone curlew sounds across the trees, it has a magical beauty.

I thought of Saxon and Viking princelings. The Thicks has a partly thwarted Phoenix ambition, to die and yet live. But the thing is itself a form of dying. The long-settled condition of these botanic infirmaries, for they exist here and there where a tidying hand has not invaded them, are a requiem. The rich deep mould of

their floor, the feeble barriers of guelder and hazel which let through the north-coast wind, the close canopy of undernourished branches which check full leafage, all these âdisadvantages' are time-protracting. For an oak, a holly, the chief enemies of existence are parasitic fungi, canker caused by sunburn, frost aphis of one kind or another â and lightning. They say that it strikes an oak more than any other tree. Once, cycling from Framlingham on a storm-black afternoon, I saw lightning fire an old oak in a park. It blazed up only a few yards away with a mighty crackle of dead and living wood.

Most of the Staverton oaks are so near death that they seem to be nothing more than gnarled drums for the gales to beat. Yet so tenacious is their hold on life that the twigs sprouting from them are still April green. And come August âLammas' growth will hide some shrivelled bole.

The mood of the Thicks depends on that of its visitor. I found it a contemplative, loving silence. Little or no birdsong. An absence of that rustling busyness created by small unseen animals. A carpet-soft humus deadened my every step. So soft was it that sparse forest flowers â sanicle shoots, wild strawberry, speedwell â can be trodden into it without injury. A sequence of glades has its own special senescence. It is like walking through an ill-lit gallery of sculpted last days. Except that here there is an endless putting off of last days.

As Staverton means a staked enclosure, what was it that was enclosed? And why were its âthicks' left to degenerate when the remainder of the forest was not allowed to? Why was it allowed to do what it liked? Yet it feels neither cursed nor abandoned. It is like a

woodland

mortuary, yet not tragic. Its enigma lies in some destiny which we now know nothing of. For some reason it was intentionally untouched â and staved in. It is grotesque, part a wood from Gormenghast, part a lecture on death, part a ruin of miscegenation. Holly props up oak; ivy alone flourishes. Wild creatures for the most part avoid it. It is botany as departure â yet neither root nor leaf ever goes.