The Toilers of the Sea

Table of Contents

THE ARCHIPELAGO OF THE CHANNEL

XI - OLD HAUNTS AND OLD SAINTS

XIV - PROGRESS OF CIVILIZATION IN THE ARCHIPELAGO

XVI - ANTIQUITIES AND ANTIQUES; CUSTOMS, LAWS, AND MANNERS

XVII - PECULIARITIES (CONTINUED)

XVIII - COMPATIBILITY OF EXTREMES

XXIII - POWER OF THE STONE BREAKERS

XXIV - KINDNESS OF THE PEOPLE OF THE ARCHIPELAGO

BOOK I - THE MAKING OF A BAD REPUTATION

I - A WORD WRITTEN ON A BLANK PAGE

III - “FOR YOUR WIFE, WHEN YOU MARRY”

VII - A GHOSTLY TENANT FOR A GHOSTLY HOUSE

VIII - THE SEAT OF GILD-HOLM-âUR

I - A RESTLESS LIFE, BUT A QUIET CONSCIENCE

III - THE OLD LANGUAGE OF THE SEA

IV - YOU ARE VULNERABLE IN WHAT YOU LOVE

BOOK III - DURANDE AND DÃRUCHETTE

II - THE ETERNAL HISTORY OF UTOPIA

IV - CONTINUATION OF THE HISTORY OF UTOPIA

VII - THE SAME GODFATHER AND THE SAME PATRON SAINT

IX - THE MAN WHO HAD SEEN THROUGH RANTAINE

XI - CONSIDERATION OF POSSIBLE HUSBANDS

XII - AN ANOMALY IN LETHIERRY'S CHARACTER

XIII - INSOUCIANCEâAN ADDITIONAL CHARM

I - THE FIRST RED GLEAMS OF DAWN, OR OF A FIRE

II - GRADUAL ENTRY INTO THE UNKNOWN

III - AN ECHO TO “BONNY DUNDEE”

V - WELL-EARNED SUCCESS ALWAYS ATTRACTS HATRED

VI - SHIPWRECKED MARINERS ARE LUCKY IN ENCOUNTERING A SLOOP

VII - A STRANGER IS LUCKY IN BEING SEEN BY A FISHERMAN

III - CLUBIN TAKES SOMETHING AWAY AND BRINGS NOTHING BACK

VIII - CANNON OFF THE RED AND OFF THE BLACK

IX - USEFUL INFORMATION FOR THOSE EXPECTING, OR FEARING, LETTERS FROM OVERSEAS

BOOK VI - DRUNK HELMSMAN, SOBER CAPTAIN

II - AN UNEXPECTED BOTTLE OF BRANDY

III - INTERRUPTED CONVERSATIONS

IV - IN WHICH CAPTAIN CLUBIN SHOWS ALL HIS QUALITIES

V - CLUBIN AT HIS MOST ADMIRED

VII - AN UNEXPECTED TURN OF FATE

BOOK VII - THE UNWISDOM OF ASKING QUESTIONS OF A BOOK

I - THE PEARL AT THE FOOT OF THE PRECIPICE

II - GREAT ASTONISHMENT ON THE WEST COAST

PART II - GILLIATT THE CUNNING

I - A PLACE THAT IS HARD TO REACH AND DIFFICULT TO LEAVE

II - THE PERFECTION OF DISASTER

V - A WORD ON THE SECRET COOPERATION OF THE ELEMENTS

VII - A LODGING FOR THE TRAVELER

VIII - IMPORTUNAEQUE VOLUCRES

167

IX - THE REEF, AND HOW TO MAKE USE OF IT

XII - THE INTERIOR OF AN EDIFICE UNDER THE SEA

XIII - WHAT CAN BE SEEN THERE AND WHAT CAN BE MERELY GLIMPSED

I - THE RESOURCES OF A MAN WHO HAS NOTHING

II - IN WHICH SHAKESPEARE AND AESCHYLUS MEET

III - GILLIATT'S MASTERPIECE COMES TO THE RESCUE OF LETHIERRY'S MASTERPIECE

VI - GILLIATT GETS THE PAUNCH INTO POSITION

VIII - AN ACHIEVEMENT, BUT NOT THE END OF THE STORY

IX - SUCCESS ACHIEVED BUT LOST IMMEDIATELY

I - EXTREMES MEET AND CONTRARY FORESHADOWS CONTRARY

III - EXPLANATION OF THE SOUND HEARD BY GILLIATT

BOOK IV - OBSTACLES IN THE PATH

I - NOT THE ONLY ONE TO BE HUNGRY

III - ANOTHER FORM OF COMBAT IN THE ABYSS

IV - NOTHING CAN BE HIDDEN AND NOTHING GETS LOST

V - IN THE GAP BETWEEN SIX INCHES AND TWO FEET THERE IS ROOM FOR DEATH

VII - THERE IS AN EAR IN THE UNKNOWN

207

BOOK II - GRATITUDE IN A DESPOTISM

BOOK III - THE SAILING OF THE CASHMERE

I - THE CHURCH NEAR HAVELET BAY

II - DESPAIR CONFRONTING DESPAIR

III - THE FORETHOUGHT OF ABNEGATION

IV - “FOR YOUR WIFE, WHEN YOU MARRY”

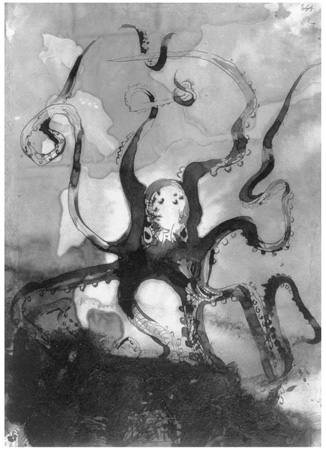

A NOTE ON THE DRAWINGS OF VICTOR HUGO

I dedicate this book to the rock of hospitality and liberty,

that corner of old Norman soil where dwells

that noble little people of the sea;

to the island of Guernsey, austere and yet gentle,

my present asylum, my future tomb.

V. H.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Drawings by Victor Hugo

PREFACE

Religion, society, nature: such are the three struggles in which man is engaged. These three struggles are, at the same time, his three needs. He must believe: hence the temple. He must create: hence the city. He must live: hence the plow and the ship. But these three solutions contain within them three wars. The mysterious difficulty of life springs from all three. Man is confronted with obstacles in the form of superstition, in the form of prejudice, and in the form of the elements. A triple ananke

1

weighs upon us: the ananke of dogmas, the ananke of laws, the

ananke

of things. In

Notre-Dame de Paris

the author denounced the first of these; in

Les Misérables

he drew attention to the second; in this book he points to the third.

With these three fatalities that envelop man is mingled the fatality within him, the supreme

ananke,

the human heart.

Hauteville House, March 1866.

Â

Â

INTRODUCTION

Graham Robb

Most eminent writers learn to protect their reputations. They capitalize on success at the risk of being accused of self-parody, avoid ridicule at the risk of becoming tedious, and appear humble in the face of public acclaim. Victor Hugo (1802â85) destroyed his own reputation so many times and with such spectacular disregard for the consequences that he seemed to have several lives to spare.

After the fall of Napoleon I in 1815, the boy poet had been the angelic voice of the restored monarchy, “the hope of the muses of the fatherland.” Ten years later, Victor Hugo was the

enfant terrible

of French Romanticism, the author of a play,

Hernani,

which filled the Comédie Française with long-haired hooligans, and a novel,

Notre-Dame de Paris,

which appeared to celebrate the victory of the 1830 Revolution. In the 1840s, he was elected to the conservative Académie Française and made a peer of the realm. The idol of the young Romantics had become respectable. As one of his former disciples put it, “What was the point of going to all the trouble of becoming Victor Hugo?”

The collapse of the monarchy in 1848 heralded a new succession of Hugos. There was the Hugo who fought on the barricades in Paris, the political exile who broadcast to his international audience from an island in the English Channel, the visionary poet, the defender of the

misérables,

the national hero who helped to found the Third Republic. The 2 million people who attended his funeral in 1885 were a fair reflection of his encyclopedic career: anarchists, feminists, war veterans, civil servants, politicians, and prostitutes. Every layer of society was represented.

This mass outbreak of Hugophilia was seen by some as evidence of the poet's hypocrisy: his continual changes of tack were attributed to cynical opportunism. Hugo's refusal to separate morality from politics had always had an inflammatory effect on his contemporaries. Before and after his death, he was insulted and admired more than any other writer: “sublime cretin” (Dumas fils); “as stupid as the Himalayas” (Leconte de Lisle); “Victor Hugo was a madman who thought he was Victor Hugo” (Jean Cocteau). Hugo might have retorted with the words he quoted in

William Shakespeare

(1864): “Remember the advice that, in Aeschylus, the Ocean gives to Prometheus: âTo appear mad is the secret of the sage.' ”

Now, in 2002, the bicentenary of Hugo's birth is being celebrated in France. The face that appears on television and on newsstands is the white-bearded sage of the Third Republic, the politically correct Father Christmas figure who used to stare down from classroom walls at children who were forced to memorize his poems. At Hugo's funeral, armed policemen confiscated the banners of socialist clubs. At his bicentenary, the boisterous rabble of his writing is being drowned out by official platitudes.

This neutralization of France's greatest writer is significant. Hugo was always the voice of his nation's bad conscience. His parents had stood on opposite sides of the great chasm in French history: the monarchy and the republic. His father was an important general in Napoleon's army in Spain. His mother, meanwhile, joined a conspiracy to depose Napoleon. For Hugo, to take one side or the other was to betray a part of his own past.

Hugo may have practiced autobiography as a form of fiction, but he grew up in a country that obsessively rewrote its own history. He saw Napoleon twice defeated and the monarchy twice restored in less than two years. In 1848 and 1871, he saw the government of which he was a member massacre hundreds of its own citizens. These traumatic events were also personal catastrophes. They showed that it was possible to follow the dictates of one's conscience and yet not be on the side of Good. Above all, they revealed the terrible truth that human battles are acted out on a background of unfathomable darkness: “The solitudes of the ocean are melancholy: tumult and silence combined. What happens there no longer concerns the human race.”

The powerful, strangely insecure language of Hugo's magnificent novel

The Toilers of the Sea,

with its sporadic omniscience, its startling images slowly hammered into unexpected truths, its relentless questions and baffling answers, is the sound of a forensic hand forcing doors, lifting lids, unearthing ghastly secrets. Baudelaire claimed that “nations have great men only in spite of themselves,” but they also have the great men they deserve. Victor Hugo, the secular god of official celebrations and poet laureate of the tourist industry, is also the Victor Hugo who wrote

The Toilers of the Sea

and other half-forgotten works of geniusâthe nervous voice of a nation whose modern history is crowded with ghosts: the Dreyfus Affair, the Vichy government and the deportation of Jews, the Algerian war, and, more recently, the rise of the National Front. As Hugo wrote, “Some crayfish souls are forever scuttling backward into the darkness.”

When Hugo wrote

The Toilers of the Sea,

a chasm lay between him and his home country. In December 1851, Louis-Napoleon (later, Napoleon III) dissolved Parliament, bribed the army, and conducted a coup d'état. Hugo hid in Paris for several days, trying to stir up a revolt. Eventually, he fled from Paris on the night train to Brussels disguised as a worker. He spent the next nineteen years in exile, most of them in the Channel Islands, first on Jersey and then on Guernsey. His polemical works

âNapoléon le Petit

and

Châtimentsâ

were smuggled off the island and inspired revolutionary movements throughout the world.

Even in exile, the supposedly monolithic Hugo changed as often as the weather in the English Channel. He was a lyric poet in

Les Contemplations

(1856), an epic poet in

La Légende des Siècles

(1859), a social reformer in

Les Misérables

(1862). All these works were rooted in his earlier life, but

Les Travailleurs de la Mer

(1866) was conceived and written entirely in the Channel Islands. It showed, triumphantly, that Hugo's imagination had thrived on banishment and defeat.

A key to the workings of this imagination can be found in the extraordinary séances conducted in the first years of Hugo's exile on Jersey. The practice of enlisting the spirits of the dead in after-dinner conversation had been introduced to the exiles as a parlor game, but the mind of Victor Hugo turned it into a terrifying series of metaphysical visions.

The Hugos and some of their fellow exiles sat in a darkened drawing room, with the sea wind rattling the windows, and were astonished to find themselves talking to Hugo's first daughter, Léopoldine, who had drowned on her honeymoon nine years before. For the next eighteen months, until one of the participants went mad, the table tapped out its mystic words: one tap for an

a,

two for a

b,

and so on. Once transcribed, these messagesâfrom Homer, Socrates, Jesus, Joan of Arc, and many othersâall sounded remarkably like Victor Hugo.

One of the stars of these séances was a moody, irascible Ocean, which appeared in the spring of 1854, twelve years before it reappeared in

The Toilers of the Sea.

The Ocean wanted to dictate a piece of music and listed its musical needs:

Give me the falling of rivers into seas, cataracts, waterspouts, the vomitings of the world's enormous breast, that which lions roar, that which elephants trumpet in their trunks [ . . . ] what mastodons snort in the entrails of the Earth, and then say to me, “Here is your orchestra.”

Hugo politely offered a piano. But, as the Ocean pointed out, a piano could never express the synaesthetic dialogue of sounds, sights, and scents. “The piano I need would not fit into your house. It has only two keys, one white and one black, day and night; the day full of birds, the night full of souls.” Hugo then suggested using Mozart as a go-between: “Mozart would be better,” agreed the Ocean. “I myself am unintelligible.”

HUGO: “Could you ask Mozart to come this evening at nine o'clock?”

THE OCEAN: “I shall have the message conveyed to him by the Twilight.”

These ghostly conversations are often used to show that Hugo was insanely gullible. He seemed to believe that this flotsam of his unconscious mind had come from beyond the grave. He showed no surprise when the spirit of Shakespeare told him, “The English language is inferior to French,” nor when he heard himself described by “Civilization” as “the great bird that sings of great dawns.”

Hugo himself knew that, if published, these séance texts would be greeted with “an immense guffaw.” His credulity was a deliberate ploy. By suspending his disbelief, he was summoning up the wild-eyed, holy sense of horror that kept the channels open between the writing hand and the deep unconscious.

The séance texts were a kind of rehearsal for his novel. Hugo was talking to his characters, conducting interviews with his own imagination. In

The Toilers of the Sea,

the tidal-wave syntax that sweeps up small details until the horizons of the page are filled with a single mighty metaphor, the thudding epigrams and crashing contrasts, the sudden silences and bathetic plunges were an attempt to provide the Ocean with its orchestra.

Hugo wrote his novelâoriginally titled L'Abîme (“The Abyss” or “The Deep”)âbetween June 1864 and April 1865. The harrowing process of revision took almost as long. The novel was eventually published in March 1866. The introduction, “L'Archipel de la Manche,” which is still the best general guide to the Channel Islands, was omitted. It did not appear until the 1883 edition.

Visitors to Guernsey today can not only talk to Hugo's ocean, they can also explore the house where the novel was written. From the street, Hauteville House, on the hill above St. Peter Port, appears to be a normal Georgian town house. Inside, it looks like a homemade Gothic cathedral. Hugo filled it with his own carvings and paintings and objects picked up on the beach or discovered in old barns. From the primeval gloom of the entrance hall to the blinding light of the “lookout” on the roof, Hauteville House is a model of Hugo's cosmogony, a seven-story poem in bricks and mortar.

It was in the “lookout” that he wrote his novel, standing up, battered by the wind, with a view of the harbor below and the thin gray line of the French coast. A glass panel in the floor allowed him to peer down through the layers of his domestic universe like a medieval god.

The intimate and grandiose architecture of the house is perceptible in

The Toilers of the Sea.

Huge blocks of text are coordinated as if they were parts of a giant sentence. The structure is littered with bizarre linguistic artifacts, picked up on beachcombing expeditions through manuals and dictionaries. And, like the house itself, the novel can be explored on several levels.

The ship that runs aground is the ship of State, piloted by a greedy hypocrite (Clubin or Napoleon III), and redeemed by a lone hero (Gilliatt or Victor Hugo). The title of the novelâliterally, “

Workers

of the SeaӉhas a socialist nuance. Technical progress and honest toil will triumph over the old feudal systems. But this was also part of a greater struggle. Gilliatt's task, like that of any engineer, is to conquer gravity and thus, in Hugo's symbolic view, the dumb weight of original sin.

At the center of the novel, the two towers of the Douvres, with the ship lodged between them, are one of Hugo's giant monograms, like the

H

of the guillotine in

Ninety-Three

or the

H

of the twin towers of Notre-Dame. This vertiginous structure is the concrete form of Hugo's mental discipline, around which the other allegories are entwined: the self-destructive nature of love, the civilizing mission of the lone hero, and his metaphysical fear of the void, embodied in that half-imagined, ungraspable creature, the

pieuvre,

“one of those embryos of terrible things that the dreamer glimpses confusedly through the window of night.”

The Toilers of the Sea

was a huge popular success, which says much about changes in reading habits. “Nineteenth-century novel” was not yet synonymous with dainty drawing-rooms and etiquette, although, even in 1866, a novel about an illiterate sailor and “the silent inclemency of phenomena going about their own business” was considered somewhat eccentric.

Five editions hurtled off the presses in the first three months. French critics were predictably frosty. In France, to insult the exiled Victor Hugo was to show allegiance to the régime of Napoleon III. One pedant published a brochure titled

A Badly Mistreated Mollusc, or

M. Victor Hugo's Notion of Octopus Physiology. Critics, said Hugo, are people who look at the sun and complain about its spots. A noble exception was Alexandre Dumas, who threw a

pieuvre-

tasting party in honor of the novel. Most writers remained silent. Like the Dreyfus Affair, the exile of Victor Hugo is one of the great moral touchstones in French history.

An English translation appeared almost immediately. Unfortunately, it sanitized the text. Gone were the underwater pebbles resembling the heads of green-haired babies, the evocation of springtime as the wet dream of the universe, and, of course, the nightmarish anatomy of the

pieuvre

with its single orifice.

British critics chortled at Hugo's extraordinary attempts at English. Captain Clubin was greeted with a hearty “Good-bye, Captain.” A “cliff ” in Scotland was called “

la Première des Quatre

” (the Firth of Forth), and the bagpipes turned into a “bug-pipe.” Hugo was sensitive to reviews and found these comments strangely discourteous. He had dedicated his novel to the people of Guernsey and even gave the first word to England: “

La Christmas de 182 . . . fut remarquable à Guernesey.

” As Robert Louis Stevenson pointed out, these blunders were part of Hugo's weird charm. In fact, his fondness for the craggy consonants of Anglo-Saxon, the mad desolation of Celtic myth, and the swirling hallucinations of fog and forest give his Channel Island novels

âThe

Toilers of the Sea, The Laughing Man,

and

Ninety-Threeâ

a curious Britishness reminiscent of J.R.R. Tolkien and Mervyn Peake.