The Trellis and the Vine (13 page)

Read The Trellis and the Vine Online

Authors: Tony Payne,Colin Marshall

Tags: #ministry training, #church

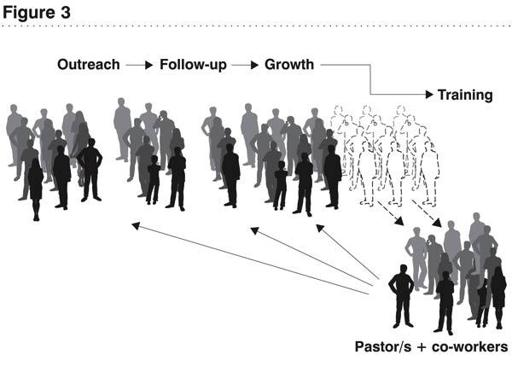

Now you as the pastor are not doing all of the ministry. You are training others to work alongside you, starting with just a few. However, the goal over time is to ‘convert’ all the disciples into disciple-makers, to train all the Christians as vine-workers—people with the conviction, character and competency to minister to others. So the number of workers grows, and the amount of ministry grows, as more and more people start prayerfully speaking the Bible’s message to others in a myriad of different ways—large and small, formal and informal, at home, at work, at church, in small groups, and one to one.

It looks more like this:

In other words, selecting some co-workers up-front is the first step towards creating a growing fellowship of workers of all different kinds. Some of these will work very closely with you, and get to the point where they themselves become trainers. They will not just do the work, but will lead and train other vine-workers.

We don’t want to get too neat and tidy about all this—as if people start wearing badges and uniforms according to whether they are ‘stable Christians’, ‘regular vine-workers’, ‘co-workers’ or ‘pastors’. Ministry is always messy because it involves real people. Some people you select as co-workers will end up dropping out or not realizing their potential. Others whom you didn’t originally start working with will come powering through and quickly become part of the core team. Over time, the line between ‘co-worker’ and ‘vine-worker’ will become very blurred, because you will be training an ever-growing percentage of the stable Christians in your congregation to be vine-workers. And as more and more Christians are trained to minister to others, the number and variety of ministries will quickly get out of hand. People will be starting things, taking initiative, meeting with people, dreaming up new ideas. Growth is like this. It creates a kind of chaos, like a vine that constantly outgrows the trellis by sending tendrils out in all directions.

There is an aspect of this growth that we haven’t yet touched upon. In Figure 3 (above), we see more and more people being ministered to because more people are being trained as vine-workers. Yet there is still only one pastor leading the whole thing and holding it together. If under God it all keeps growing, then we’ll need more pastors, more overseers and more leaders.

Where are they going to come from?

Chapter 10.

People worth watching

Where do pastors and other ‘recognized gospel workers’ come from?

The traditional answer—and it is a very good answer—is that they are called and raised up by God. Jesus asks his disciples to “pray earnestly to the Lord of the harvest to send out labourers into his harvest” (Luke 10:2). Evangelists, pastors and teachers are the gifts of the ascended Christ to his church (Eph 4:10-12).

However, to say that God provides pastors doesn’t really help us all that much in knowing what part human action plays in the process. We could say, for example, that people only become Christians because God works in their hearts, but this doesn’t meant that evangelism is a waste of time. On the contrary, it is precisely by means of prayerful evangelism that God graciously converts people and brings them to new birth.

God’s action and human action aren’t alternatives, like deciding who will perform the action of washing up tonight. God works in our world, but he isn’t a creature. He’s the creator, and his characteristic mode of operation is to work in and through his creatures to achieve his purposes. “I planted,” says Paul, “Apollos watered, but God gave the growth” (1 Cor 3:6).

So our question would be better framed like this: By what means, or through what agency, does God call and raise up the next generation of pastors and evangelists?

We want to suggest in this chapter that it is by pastors actively recruiting suitable people within their churches, and challenging them to expend their lives for the work of the gospel. It is by doing what Paul urged Timothy to do: “…and what you have heard from me in the presence of many witnesses entrust to faithful men who will be able to teach others also” (2 Tim 2:2). Commenting on this passage, Broughton Knox says:

It must be remembered that it is the duty of ministers in the congregation to care for the spiritual welfare of that congregation, and one of the primary areas of care is the continuance of the ministry of God’s word within the congregation. Thus Paul reminded Timothy that it fell within his ministerial duty to see that the ministry of God’s word was effectively continued. Just as he had the truth from Paul and his fellows, he was to hand it on to faithful men who would be able to teach others also (2 Tim 2:2)—four generations of apostolic succession in the apostolic word.

[1]

In many contexts today, this task of raising up the next generation is left to ‘someone else out there’. It’s the denomination’s job, or the seminary’s. Or perhaps we leave it to God to put the idea in people’s hearts without any external intervention.

Whatever the reason, most of us are reluctant to challenge people to full-time gospel work. Before we go any further, we should deal with some common questions or objections to the idea of ‘ministry recruitment’.

Four common questions

Question 1: All believers are called to serve, so why should some be called into ‘ministry’?

One of our real problems is the word ‘call’. We are used to thinking of the ‘call to ministry’ as a kind of individual, mystical experience, by which people become convinced that God wants them to enter the pastorate.

However, when we turn to the New Testament, we find that the language of ‘calling’ is not really used this way. It is almost always used to describe how God graciously ‘calls’ or summons people to follow him or repent, with all the privileges and responsibilities this involves. Here is a representative selection of verses:

And we know that for those who love God all things work together for good, for those who are

called

according to his purpose. For those whom he foreknew he also predestined to be conformed to the image of his Son, in order that he might be the firstborn among many brothers. And those whom he predestined he also

called

, and those whom he

called

he also justified, and those whom he justified he also glorified. (Rom 8:28-30)

…who saved us and

called

us to a holy calling, not because of our works but because of his own purpose and grace, which he gave us in Christ Jesus before the ages began… (2 Tim 1:9)

…having the eyes of your hearts enlightened, that you may know what is the hope to which he has

called

you, what are the riches of his glorious inheritance in the saints… (Eph 1:18)

…I press on toward the goal for the prize of the upward

call

of God in Christ Jesus. (Phil 3:14)

God is faithful, by whom you were

called

into the fellowship of his Son, Jesus Christ our Lord. (1 Cor 1:9)

But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who

called

you out of darkness into his marvelous light. (1 Pet 2:9)

I therefore, a prisoner for the Lord, urge you to walk in a manner worthy of the

calling

to which you have been

called

… (Eph 4:1)

And let the peace of Christ rule in your hearts, to which indeed you were

called

in one body. And be thankful. (Col 3:15)

To this end we always pray for you, that our God may make you worthy of his

calling

and may fulfil every resolve for good and every work of faith by his power… (2 Thess 1:11)

The Bible doesn’t speak of people being ‘called’ to be a doctor or a lawyer or a missionary or a pastor. God calls us to himself, to be Christian. Our ‘vocation’ (which comes from the Latin word ‘to call’) is to be Christ’s disciple and to obey everything that he commanded—including the commandment to make disciples of all nations. In that sense, all Christians are ‘ministers’, called and commissioned by God to give up their lives to his service, to walk before him in holiness and righteousness, and to speak the truth in love whenever and however they can.

However, even though we have been emphasizing in this book the ‘ministry of the many’, it is not in order to sideline the ‘ministry of the few’ but to create the conditions under which it, too, will flourish. When we train disciples to be disciple-makers, we will also inevitably discover some godly gifted people who have the potential to be ministry leaders—to be given the privilege, responsibility and stewardship of being set apart to preach the gospel and lead God’s people.

The two main categories of these ‘set apart’ people in the New Testament are the elders/pastors/overseers who are charged with teaching and leading congregations, and the members of Paul’s apostolic gospel team, the ‘fellow workers’ and ‘ministers’, who labour for the spread of the gospel. These categories are not hard and fast, as if the pastors are not also to evangelize (cf. 2 Timothy 4:5 where Timothy is told to “do the work of an evangelist”), or as if Paul the evangelist did not also labour to build up the Christians who had been converted under his ministry. In the end, the distinction between ‘evangelizing’ and ‘pastoring’ is a blurry one.

This, in fact, is one of our problems in thinking and talking about this whole area. It all seems so blurry! And the standard Western pattern of having a professional paid pastor or clergyman doesn’t always correspond. We struggle to speak in the language of the Bible not only because of the often confusing and inconsistent way that language has been used in Christian history, but also because the Bible itself does not bother to come up with precise labels. Consider these distinctions:

• All Christians should teach each other (Col 3:16), and yet not all are teachers (1 Cor 12:29; Jas 3:1).

• All Christians should ‘minister’ to one another (1 Pet 4:10-11), and yet some are set apart as ‘ministers’ (or ‘deacons’ or ‘servants’, depending on your translation, in 1 Timothy 3:8-13; see also Paul’s team members, whom he calls ‘ministers’).

• All Christians should abound in the work of the Lord (1 Cor 15:58), and yet Paul regards himself and Apollos as ‘fellow workers’ labouring among the Corinthians for their growth (1 Cor 3:5-9).

• All Christians should make disciples and speak to others about Christ (Matt 28:19; 1 Pet 3:15), and yet some are identified as ‘evangelists’ (Eph 4:11).

There is both continuity and discontinuity. We’re all in it together, and yet some have a special role. When we try to discern what it is that makes that role special in the New Testament, it’s not full-time versus part-time, or paid versus unpaid. (This is a reality that pastors in the developing world understand very well.) It’s not that some belong to a special priestly class and others don’t. It’s not even that some are gifted and others aren’t, because all have gifts to contribute to the building of Christ’s congregation.

The key thing seems to be that some are set apart or recognized or chosen—because of their convictions, character and competency—and

entrusted

with the responsibility under God for particular ministries. This entrusting will happen through human processes of deliberation and decision, but it remains a solemn divine trust, a stewardship of the gospel for which we are answerable to God (cf. 1 Cor 4:1-5). It is not a ‘career decision’ that people make casually on their own, and then equally casually decide to leave aside to move onto something else, perhaps when it gets hard or inconvenient. It’s worth noting with what seriousness Paul charges Timothy to stick with his ministry in 1 Timothy 4.

Perhaps, for the sake of convenience and clarity, we should call these people ‘recognized gospel workers’—not recognized because they are more spiritual or closer to God or have special powers, but recognized and chosen by other elders and leaders to fulfil a particular role of stewardship, like the captain of a team or the board of directors of a company.

This leads us to a second obvious question.

Question 2: Shouldn’t we wait for people to ‘feel called’, rather than urging them into full-time gospel work?

It has become traditional for the personal, subjective sense of ‘calling’ to be the determinative factor in people offering themselves for full-time Christian ministry. Perhaps it is a longing for the dramatic personal commissioning experienced by Moses at the burning bush, or by Isaiah in the temple; or perhaps it stems from a desire to anchor our decision to pursue ministry outside ourselves in the call of God. Whatever the reason, it is common to wait for someone to say to us that they ‘feel called to the ministry’ or that they ‘think that God is calling me to be a missionary’ before we start to assess their suitability.

The Bible does not speak in these terms. Search as we may, we don’t find in the Bible any example or concept of an inner call to ministry. There are some who are called directly and dramatically by God (like Moses and Isaiah), but it is not a matter of discerning an inner feeling.

Almost universally in the New Testament, the recognizing or ‘setting apart’ of gospel workers is done by other elders, leaders and pastors. Just as Timothy was commissioned in some way by the elders (1 Tim 4:14), so he was to entrust the gospel to other faithful leaders who could continue the work (2 Tim 2:2). Likewise Titus was given responsibility by Paul for the ministry in Crete, and he in turn was to appoint elders/overseers in every town (Titus 1:5-9).

Perhaps it is right in this sense to speak of people being ‘called’ by God to particular ministries or responsibilities—so long as we recognize that this ‘call’ is mediated through the human agency of existing recognized ministers. Luther puts it like this:

God calls in two ways, either by means or without means. Today he calls all into the ministry of the Word by a mediated call, that is, one that comes through means, namely through man. But the apostles were called immediately by Christ himself, as the prophets in the Old Testament had been called by God himself. Afterwards, the apostles called their disciples, as Paul called Timothy, Titus etc. These man called bishops as in Titus 1:5ff; and the bishops called their successors down to our time, and so on to the end of the world. This is the mediated call since it is done by man.

[2]

We shouldn’t sit back and wait for people to ‘feel called’ to gospel work, any more than we should sit back and wait for people to become disciples of Christ in the first place. We should be proactive in seeking, challenging and testing suitable people to be set apart for gospel work.

Question 3: Can’t we be involved in ‘gospel work’ without being paid?

We have been suggesting so far that people should be chosen or commissioned as gospel workers for the preaching of the gospel and the shepherding of God’s people. Traditionally, we would speak about such people being called to missionary work or to the ordained ministry, and in most Western churches these would be full-time positions paid for by the gifts of God’s people.

However, the method of payment and the number of hours worked per week are not the defining factors. In the New Testament, it’s hard to find many examples of ‘full-time paid ministry’, except perhaps Paul at some stages of his mission—as in Corinth where he started out making tents with Priscilla and Aquila, but then was “occupied with the word” when Silas and Timothy arrived (probably with a financial gift from the Macedonians; see Acts 18:1-5). Even during the three years he was in Ephesus, teaching daily in the lecture hall of Tyrannus and not ceasing “night or day to admonish everyone with tears”, Paul still provided for his own needs with his own hands (Acts 20:31-34; cf. 19:9).

All the same, the Bible does affirm that those who preach the gospel should make their living from the gospel (1 Cor 9:1-12; Gal 6:6). Even if we commence our ministry by supporting ourselves, it is right for God’s people to provide for their missionaries and teachers, at least in part. Within this framework, various arrangements are possible: part-time work and ministry (like Paul’s ‘tent-making’); financial support from Christian friends; full-time paid ministry funded through a congregation, a denomination or a parachurch organization; and so on. Much depends on the customs and wealth of the society.