The True Detective (2 page)

Read The True Detective Online

Authors: Theodore Weesner

Tags: #General Fiction, #The True Detective

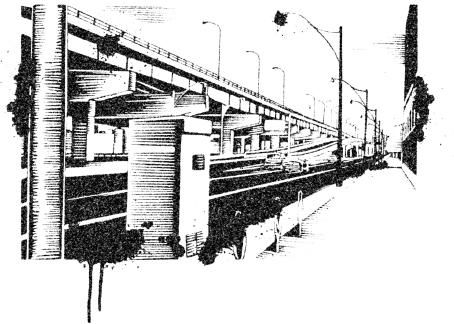

A new bridge bypassing Portsmouth offers a view that could be from a plane. Below, where the river opens to the Atlantic, are the town’s older bridges, the Route 1 Bypass and the Memorial Bridge. There, too, are its white and blue and cream-colored pleasure boats in stalls, its Naval Shipyard work sheds painted battleship gray, and the immediate merging of sky, river mouth, and ocean. Close upon the shore are the town’s brick buildings and narrow streets, pressed by rows of wooden houses and old tree tops, held throughout by salt water washing into the town’s coves and harbors, creeks and bays. Directly under the bridge a depth of water pours one way or another in its tidal slide, and as always a lobster boat is sputtering by, leaving a thin white wake in the swollen green surface, drawing along a gull or two like toys on a string.

The antique seaport of thirty-odd thousand is on the northern border of New Hampshire’s momentary coastline, and the

wide river coming and going is the Piscataqua. The new bridge turning through the sky is spliced into Interstate 95, three lanes going each way, leaving the ground like a long line drive, curving east in its trajectory north, cresting above the water at 165 feet—a dozen feet less at high tide—and returning to earth in another state. Southbound (

Live Free or Die/Bienvenue Au/New Hampshire

) and northbound (

Welcome to Maine/Vacation Land

), the green superstructure is intended to carry civilization into New England’s high corner well into the coming century.

Sea sounds and smells are here in all seasons. Over land and water gulls and sea ducks complain and argue, buoys and ships’ bells clang and hammer, and the clam flats and rock formations with their catch basins and green beards—unlike the blond beaches on the nearby ocean proper—perk and hiss and send off their foul breath at low tide. There are old docks and piers and seawalls around town, too, covered with generations of minuscule barnacles and crustaceans, which at a distance are not dissimilar from other colonies up on shore. There is life underwater, too, where seaweed-black lobsters the size of baseball gloves thumb-strut throughout the dark mystery as if they have seen it all, as if there is nothing new under the sun.

On land, where the town is in the process of becoming a small city, wood-framed houses along the narrow old streets are being salvaged and painted yet again, and the occasional red brick mill or shoe factory is being converted to offices, apartments, boutiques, cafés. It is a town being rediscovered and repopulated, and along its old waterfront streets and in its wooden-floored mom-and-pop grocery stores, the term

mixed blessing

has found new currency, But so, elsewhere in town, have the terms

paradise,

and

pride,

and not so rarely,

San Francisco of the East.

When the local lieutenant of detectives dresses up it is in a necktie and possibly a V-neck sweater under a wool shirt jacket

from Kittery Trading Post; not dressing up, he dispenses with the necktie. An early riser, he often takes a walk in his town on Saturday morning, while his wife Beatrice sleeps in. He walks in town, or about the waterfront, or through a neighborhood. He may walk through one of the old downtown cemeteries and try to perceive something of life in a reading of markers. Or he may drive to one of the nearby beaches, to stroll and see what has washed up overnight. He will pick up broken glass if he sees it, if its edges have not been washed smooth, and deposit it in a trash barrel as he returns to his car. And he may stand for a time near the seawall at Wallis Sands and watch gulls and squads of sandpipers work the beach within its roar and mist, as waves roll in and break and leave behind a glistening effervescence of table scraps.

What he enjoys above all is to watch the far-off smudges of boats to see if they are advancing, like time, on the horizon. A child’s pastime, he often thinks. And he often thinks, too, that it is one of the pastimes to which he would introduce children, if he had children, even as this thought has reminded him lately of an account by a lawyer acquaintance whose path he is forever crossing at the courthouse or in the police station. More than once, in elevator and marble lobby, the man has told him of walking with his son and daughter on the beach at Ogunquit, passing through the grassy dunes and happening upon two naked men lying together—well, more than lying together, the man has said, one man, it seemed, but then two—just as the sun was coming up and he was walking with his son and daughter.

Gilbert Dulac is fifty-two years old and twenty-six years a policeman, an overweight, oversized immigrant of French Canadian birth—he carries 260 pounds on a frame six feet four inches tall—and he has regarded the town as his for a dozen years or more. The feeling is a consequence, he knows, of being a policeman, of being a detective and the lieutenant of detectives,

and of the town being small enough to understand, but also of being an immigrant, even if it was only to shift down, some thirty years ago, from Quebec, more as a neighbor marrying in than as a foreigner putting down roots. Like other immigrants, as immigrants know if others do not—as they believe their seriousness to be the country’s secret weapon—he is more aware of the ideals of his adopted land and life than are the natives, and it is this added charge which gives him satisfaction in his self-appointed role, one he exercises quietly, as town father in an American town.

Everyone should be so lucky, he reminds himself ever more often as time slips along and his horizons seem to diminish at a quicker rate. Children would have been the greater good luck, he has always thought; that he has none is his life’s only deep-seated regret. Children, just one or two, would have provided all that he and Beatrice might ever need or want to move on into the shadows ahead, and into the darkness. He’d have them out this morning, in fact; he’d have chased them out of bed whatever their ages and taken them for a stroll on the beach, just as he always went with his own father on Saturdays when he was a boy and his father was free from work, when they’d take their sea green Hudson Hornet down to the garage and hang out with the other men and boys and speak of cars and motors, of geese and Atlantic salmon, of Rocket Richard, of Lindsay and Howe.

It was in 1981 then that an incident happened to startle the town in its headlong rush into restoration, new brick walkways, and new taxes. On a Saturday evening in February, a twelve-year-old boy walking home close to downtown disappeared, leaving only traces of circumstantial evidence. Like a creature lifting out of the water, the incident sent a chill through the area, stole a beat in the town’s preoccupied preening upon its new wardrobe; all the world paused, if it knew it or not.

ART

O

NE

AGAZINE

P

HOTOGRAPHS

SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 14, 1981

1

H

ERE IS

E

RIC

W

ELLS

,

ON

V

ALENTINE

’

S

D

AY

,

LYING ON THE

living room floor, giving love a chance. Chin in hand, he keeps catching himself looking all the way through the TV screen where otherwise, on buzz saw feet, the Roadrunner is zipping everywhere. The old screen’s black-and-white images don’t quite matter now. Red colors keep coming up there. Blushes of valentine red. He is twelve years old and the colors are raising a warmth in him.

The card was in his desk at school yesterday. At the time he could only sneak a glance, but as he carried it home after school, trying to ignore that it was in his pants pocket, bending with his leg, its red colors kept stirring in him. Taking it into his bedroom, he closed the door. He looked at it and looked at it. If valentines were such mush, he wondered, why did it feel so good?

He gives the Roadrunner another try, until the feeling is in him again. He thinks, yuck. Then he thinks, this could be love, and catches himself tittering all the more as he tries and tries not to guess who could have put the dumb thing in his desk.

From the kitchen, close by, his mother says, “Eric, at least come have some toast.”

Toying with a Matchbox car, he doesn’t say anything. Always before he would have answered. The sensation is in him and he doesn’t answer in the first moment and then not at all. Nor does he feel anything like hunger. Their apartment is small, and his mother is hardly a dozen feet away. How could a Navy Seal, he wonders—he’s been dreaming for months of someday joining the U.S. Navy Seals—feel like this about a valentine?

M

ATTHEW

,

LYING IN

bed with his eyes closed, is not asleep. There are two roll-away beds in the partitioned end of the apartment he shares with his little brother, but the winter sun seems this morning to heat only his own. Matthew is fifteen. His mood is terrible. The smell of chili cooking out there angers him and vaguely he wishes he were anywhere but where he is.

He gives a thought to a girl in school, a black girl of all things, who spoke to him yesterday, who seemed often lately to flirt with him. To another girl, over something in algebra, she said, “Let’s ask Matt Wells. He always has his work done.”

She was teasing; he never had his work done anymore. But there was her smile and there, too, were several tiny gold rings on the fingers of one hand and a gold earring in her ear. The combination suddenly struck him: gold and chocolate.

But lying in bed now within the aroma of chili, his mood is so awful he is close to tears. When he knows his mother has opened the door, he keeps his eyes closed and lets his anger thrive on her presence.

“Matt, don’t you think it’s time you got up?”

He holds.

“Matt,” she says.

Still he holds.

“Matt!” she says.

“What?”

he says.

“I know you heard what I said.”

He doesn’t respond. He stops himself from shouting, or from collapsing within.

“Matt, you’ve got to stop being so hard on everybody,” his mother says. “We can’t live like this.”

G

UIDING ONE OF

his paint-worn Matchbox cars, Eric gives an uncertain ride to a pair of plastic soldiers. Dumping the pair on the other side of a gorge, he drives back to pick up two more. He changes his mind, though, and glances over where the Roadrunner is still zipping around. That bird is so dumb, he thinks. Turning onto his back, he places his hands under his head and looks into the universe where there used to be but a ceiling.

“Eric, you don’t have a fever, do you?” his mother says.

“Nope.”

“Are you sure?”

He doesn’t respond.

“I wish you’d eat something,” she says, although on a pause her wish disappears with her back into the kitchen.

Returning from his journey, Eric looks once more at the television screen. He and the nineteen-inch, black-and-white set are the same age, and too often in her nostalgic moments his mother has told him that when she brought him home from the hospital they spent hours together watching everything that appeared on the tube. Except when he was nursing, she always adds, which was practically all the time. Maybe a year ago, when he was old enough to tell her how icky it made him feel when she talked like that, she told him that someday he’d enjoy recalling such things as how he put on his first pounds.

Well, here it is, he thinks. This is it. Sitting up, but not by choice, and in the grip of something serene, he touches his chin to a bridge between his knees. His insides continue on their spinning ride into the heavens. He’d have to admit—these things don’t feel bad, these valentines and thoughts. They feel good right there at the tip of his spine, in the center of all that he never tells.

A

S THE FREEDOM

of Saturday morning is pleasantly under way, Claire is cooking a pot of chili, on consignment from the Legion Hall where she works weekends as a waitress. The weather outside is unusually warm—a February thaw—and she cannot resist humming a little as she guides a wooden spoon through the deep mix. She enjoys cooking. All her life she has enjoyed Saturday mornings. They are her favorite hours of the week, the only time she hums.

Otherwise she is a packer at Boothbay Fisheries. Growing up in rural Maine, leaving school in the ninth grade, Claire has worked at the fishery eight years now, since her husband left—his whereabouts are unknown—and since she moved here with her two sons. If Claire is worrying over anything this unusually pleasant morning, it is her oldest son, Matt. He seems so unhappy anymore, seems to be going backward instead of forward. If only she could tell him something helpful. If only she could get him to stop being so mean to his little brother. And to himself, she thinks. She wonders if it’s too late to dish out a good spanking. Would it do any good? Would it make things worse?

W

HO WOULD BELIEVE

it, Eric thinks, as he finds himself gazing yet again into the mystery overhead. He’s never gone cuckoo like this before. His dreams have always been to build things.

He’d use his vehicles to bulldoze roadways and airstrips; he’d throw pontoons over streams or bridge them with Popsicle sticks, and use rope and winch to save whatever trucks and troops he happened to allow to slip in their passage from one side to the other.

Combat Naval Engineers

was one of the neatest names he’d ever heard. So was

Airborne Rangers. Frogmen. Special Forces.

The names made his scalp sing, made his loins tingle, called up in him an urge to go out and build a fort or climb a tree. Who would believe something like this might so easily get in the way? Girls? Valentines?