The Truth About Death (17 page)

Read The Truth About Death Online

Authors: Robert Hellenga

Jack and Sally will be back in time for the performances of

Romeo and Juliet

. And then, unlike Olive, I’ll be turning back, back to Galesburg, where I’ll live the life I’ve been given. Bart is dead. Louisa is dead. Hildi is dead. Simon is dead. Olive is dead. Everything that I know about them happened in the past. That’s just the way things are, just the way Olive explained them to me. I’ll sit at the library table in Simon’s

tower, surrounded by great works of art, though I’ll probably change things around as soon as I get home. I’ll have to give it some thought. I’m aware, of course, of the limits of great art. Even of the greatest art. You can’t eat it or drink it. You can’t curl up on it and go to sleep. It won’t keep you dry if it’s raining or warm if it’s snowing. It won’t keep you afloat if you’re drowning. It won’t cure a cold or replace a broken hip. Well, you can’t explain it, but then you can’t explain any of the great mysteries, can you? A sword blade in an old painting flickering with the light of burning towers; a dog extending the paw of affection; the tip of a lover’s finger tracing your name on the inside of your thigh; Renaissance angels balancing effortlessly on stepping-stone clouds; your first oyster.

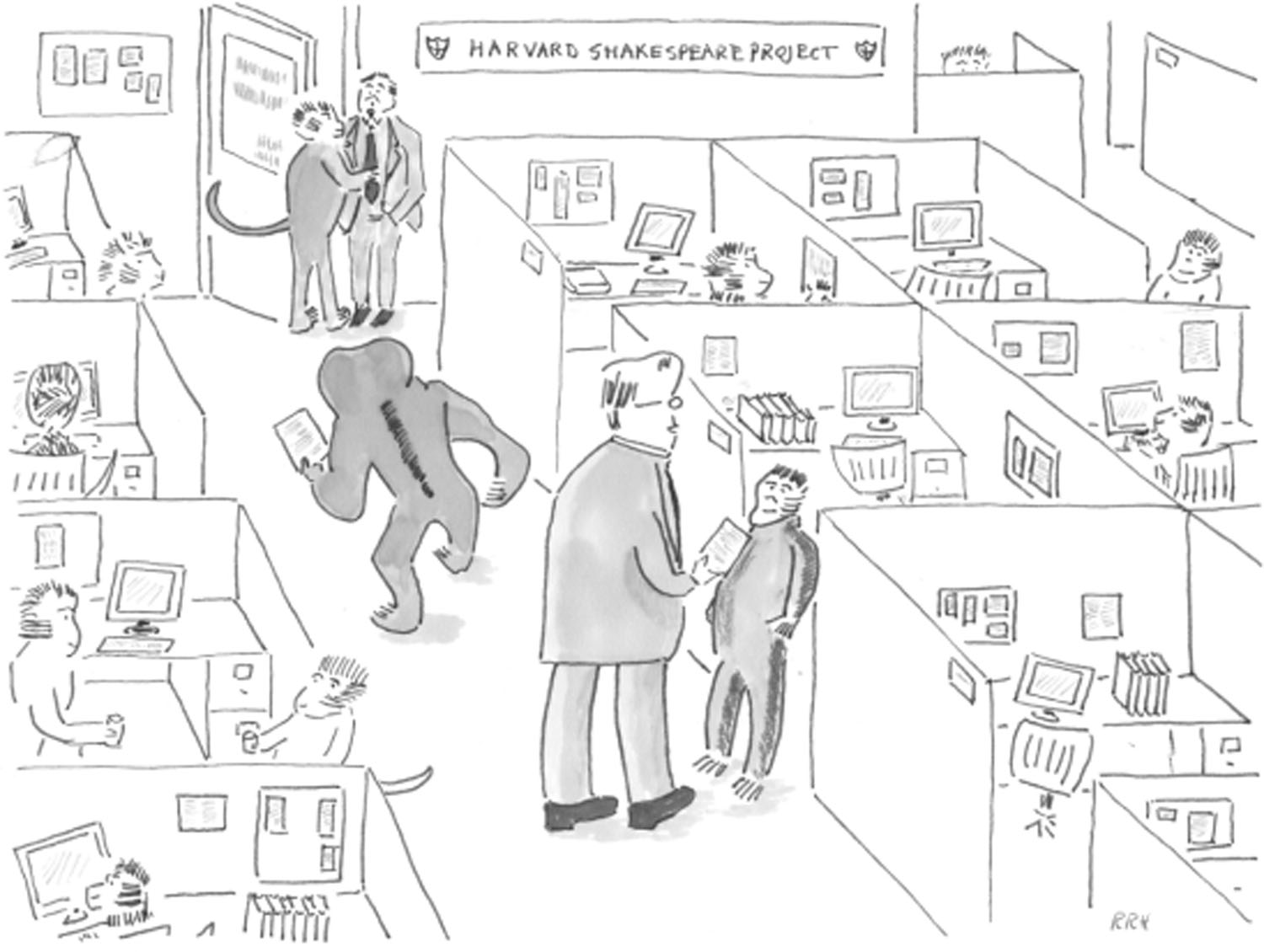

I’ll look through our scrapbooks of cartoons too, and I may even sit down at my drawing table and sketch some of Simon’s ideas—I have a long list. But later. I already have too much on my plate—classes to prepare, a session to chair for the

CAA

Conference in Chicago, a plenary lecture to write for the International Congress on Medieval Studies in Kalamazoo, and an exhibit to curate for the Morgan Library.

Just one more thing, though, before I go. I’m going to leave my cartoons with you. Six of them. So you can judge for yourself. But the last one—“The Truth About Death”—I’m going to keep to myself till I hear from Bob Mankoff at the

New Yorker

. It shouldn’t be long now. He’s got Jack and Sally’s landline number here in New York, he’s got the number of the new iPhone that Jack gave me, and the number of my landline in Galesburg, and he’s got my street address and my e-mail address. I expect to hear from him any day.

“

By crikey, Wilson, it’s the lost funeral home of the elephants

.”

“Well, I suppose it was bound to happen sooner or later.”

“What happened to all the wind turbines?”

“ ‘To be or not to be, that is the question.’ Good, now we’re getting somewhere.”

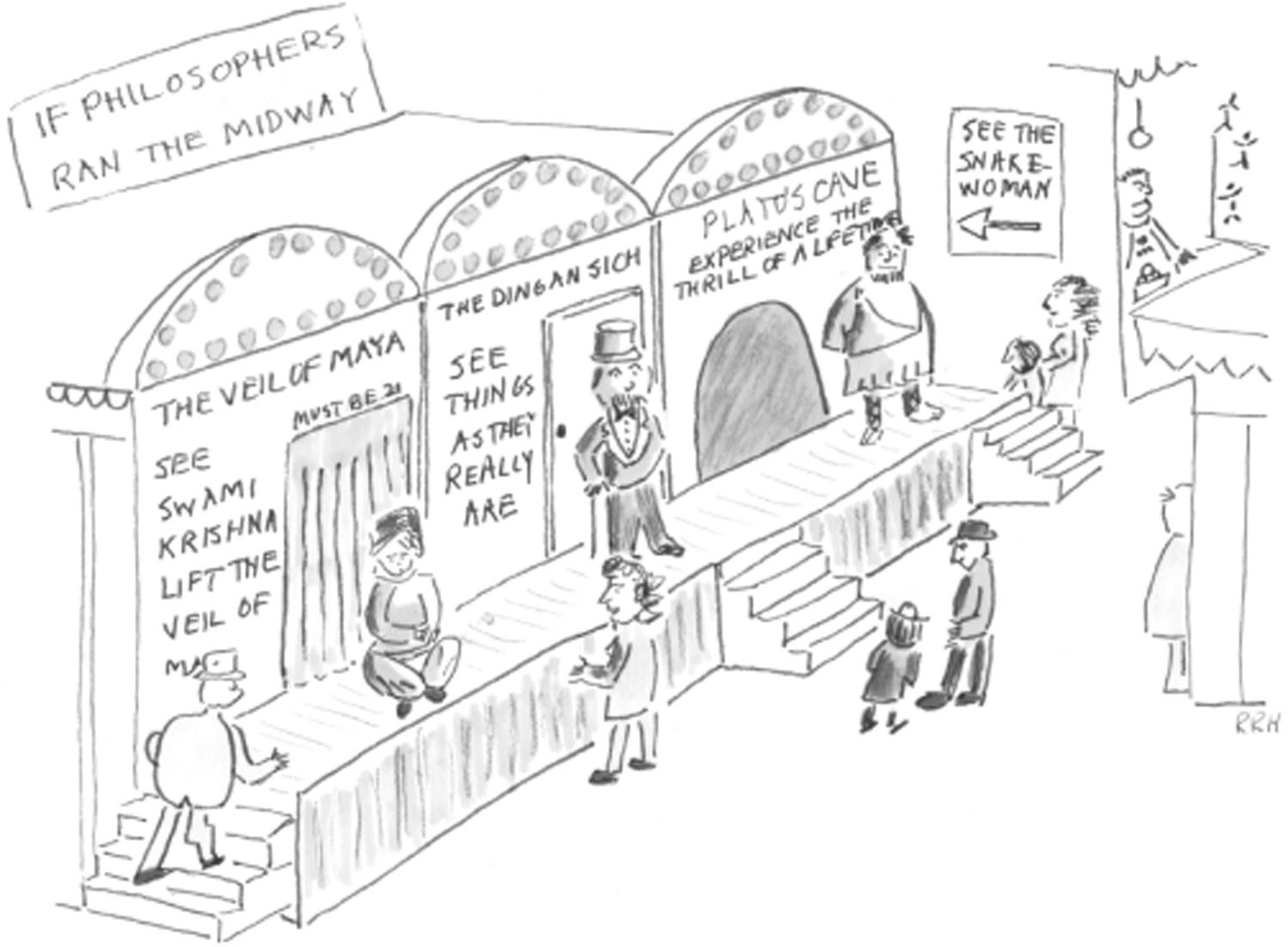

“Daddy, you promised we could see the

Ding an sich.”

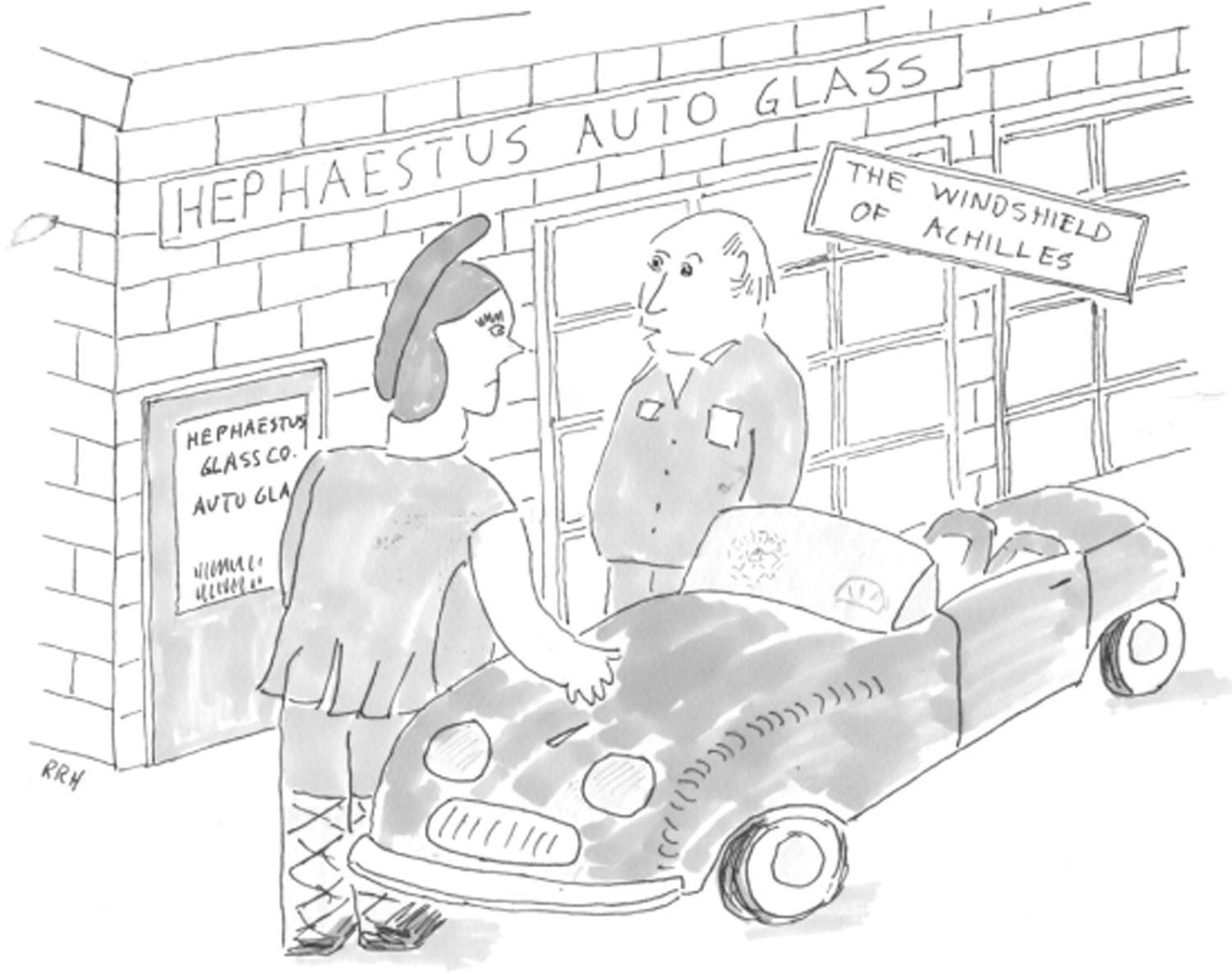

“I can have her for you by tomorrow noon.”

I was in Florence, Italy, when my father died. It was Easter Sunday and I was staying with old friends, the Marchettis, in their apartment near Piazza delle Cure, a quiet neighborhood on the north edge of town that you entered from Via Faentina. We hadn’t gone into the center for the big Easter celebration, but we’d watched the dove and the exploding cart on television.

We were just sitting down to our first course—a rich broth thickened with egg yolks—when we got a telephone call from my sister. Signora Marchetti answered the phone. My sister didn’t speak Italian, but she managed to make herself understood, and Signora Marchetti waved me to the phone in the small entrance hallway.

“Are you ready for this?” my sister said.

“I’m ready.”

“Dad’s dead,” she said. “Out at the club, he fell down in the locker room. Drunk. They couldn’t rouse him. He was dead by the time they got him to the hospital.”

“I thought they kicked him out of the club?”

“He got reinstated. He got a lawyer and threatened to sue them.”

My father had taken up golf late in life. He was a natural athlete and soon competed with the club champion. After my mother’s death he’d bought a small Airstream trailer and rented space on a lot across the road from the club entrance so he wouldn’t have had to drive home at night if he stayed late at the bar, which he often had.

“Where are you now?” I asked.

“I went out to the trailer earlier just to have a look, but I’m at the house now. Dad’s house.”

“It must be pretty early.”

“Seven o’clock,” she said.

I pictured my sister, Gracie, in the breakfast nook of the kitchen we’d grown up in, a lovely Dutch Colonial house about a mile north of town—a house that my father had built himself with help from

his

father. I pictured her sitting on the built-in blue bench at the built-in blue table, the cord from the phone on the wall stretched over her shoulder.

“What are you doing?” I asked.

“Just sitting here.”

“How are you?”

“I’m fine, in fact. How about you?”

“I’m fine too.”

“Have you met up with your friend yet?”

I’d come to Florence ostensibly to borrow one of Galileo’s telescopes for the Galileo exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago, where I was employed as an exhibit developer. But really I’d come to see a woman with whom I was madly in love, a Scottish-Italian fresco restorer, Rosella Douglas, who was working on the frescoes in the apse of Santa Croce.

I looked up at the Marchettis eating their soup at the long table in what was a combined kitchen–living room–dining room. Was someone listening to me? Luca was the only one who understood English, but he was seated at the far end of the table next to his grandmother.

“She’s skiing in the Dolomites,” I said. “She’ll be back tomorrow night. I’m going to meet her at the station. Have you called people yet?”

“I’m going to do that today.”

“Do you want me to come home?”

She laughed.

“What about the funeral?”

“His body went to the junior college. They did the removal last night. They’ve started a mortuary science program. They’ll cremate what’s left—send us the ashes.”

“Dad was full of surprises, wasn’t he?”

“We’ll have to have some kind of memorial service when you get back. Maybe out at the cemetery.”

My sister and I had been looking forward to this moment, but we hadn’t really planned ahead. “Whatever you want to do will be fine,” I said. “You’re the one who’s had to put up with him.”

“Sometimes I think I should have moved away like you did.” But then she met Pete, and that was that. No way Pete was going to leave Green Arbor. Though they were divorced now, and Pete had in fact left Green Arbor. Probably to get away from my father, who had treated him like an errand boy.

There were sixteen of us at the long table. Signora Marchetti (Claudia) had kept a bowl of soup warm for me. Chiara, who was my age, forty, put it on the table in front of me and stood for a moment with her hand on my shoulder. I’d spent a year at the Marchettis’ as an exchange student when

I was in high school, and then again when I came back to Florence on a study-abroad program, and then at various other times over the years. Chiara was like a second sister, and Luca like a younger brother. I got on well with all of them and with their cousins and aunts and uncles and with the grandmother, Nonna Agostina, who was seated in the place of honor at the head of the table.

Faces turned toward me as I took my place at the opposite end of the table from Nonna Agostina.

“My sister,” I said. “Calling to wish me a happy Easter.”

I had to make a conscious effort to suppress my relief, my sudden joy, though in fact it was more complicated than that. I was glad that my father was dead, but I wasn’t glad that I was glad. I would have preferred to be grief-stricken. And I was saddened by the sharp contrast between my own little family—Gracie, Dad, and me—and the extended family—four generations—passing their empty plates to Chiara and Luca, who were helping their mother and father clear the table. But the soup was delicious, and so was the roast baby lamb. Sensation is sensation.

When I first heard of the Oedipus complex at the University of Michigan—we were reading

Oedipus

in a “Great Books” course—I knew exactly what Freud was talking about. Dad had become more and more abusive toward my mother, who suffered from tic douloureux. She was a lovely woman, small in stature, but bighearted, generous-spirited, deeply religious. She played the organ and directed the choir at Methodist church.

You just married me for the money,

he’d say to her. Drunk.

For a free ride.

It would have been a blessing if he’d died first. She could have lived out her last years in peace instead of in a nightmare.