The Twilight of the American Enlightenment (8 page)

Read The Twilight of the American Enlightenment Online

Authors: George Marsden

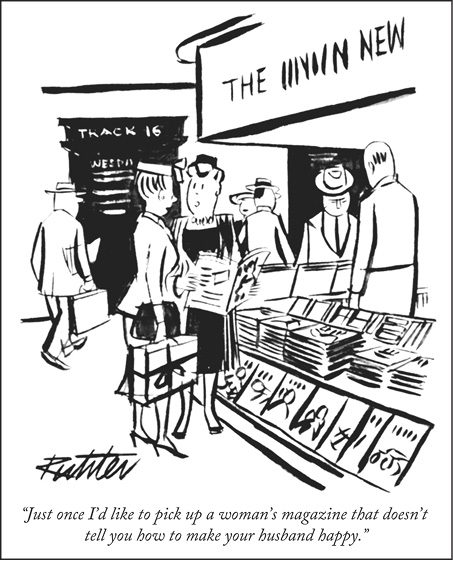

Of all the popular analyses of “modern man,” however, a late entry, Betty Friedan's 1963 book

The Feminine Mystique

, proved to have by far the most traceable impact in fostering social change. One of the great unspoken assumptions of the social discourse of midcentury America, an assumption intertwined with the enlightenment trust in rationality and the individual, was that the discourse was essentially about males. Friedan herself used the term “modern man,” but when she used it, the great difference was that she insisted on the genuinely inclusive sense of the term. So when Friedan, like the other analysts, examined self-realization versus self-alienating conformity, she applied the diagnosis to the other half of the “modern”

population that was invisible in most of the other analyses.

14

Mischa Richter, June 14, 1958,

The New Yorker

Like many of the other social commentators, Friedan was alarmed by the conformity and uniformity of the suburbs, but in her case the concern arose from her own experience. Betty Goldstein (her maiden name) had been an honors graduate from Smith College in 1942. During and after the war, she had

lived in Greenwich Village and worked as a reporter for a labor magazine. She married Carl Friedan in 1947, and after

her pregnancy with their second child was forced to give up her job. She and Carl, a theater producer, moved to various suburbs, where she raised a family and attempted to do a little reporting on the side. Her illumination came in 1957, when she was asked by the women's magazine

McCall's

to write an article on the fifteenth anniversary of her Smith graduating class. She found that many of her classmates shared her frustrations with raising children in the suburbs and living in the shadow of their husbands' more exciting worlds. She also found the members of the class of 1957 to be passive and conformist. So instead of writing the article on the “togetherness” of women that

McCall's

wanted, she issued a sharp call for liberation that none of the women's magazines would publish. She did find an editor at Norton who liked her idea as a book, however, and after five years of research and writing she finished her game-changing task.

15

Since Friedan's point of reference was her own experience as a college-educated woman living in the suburbs, when she spoke of modern “man,” she, like the other analysts, was not thinking of a wide and diverse range of American men and

women, but rather of the “modern” middle-class person of the cities and suburbs. Friedan was distressed mainly by the psychological implications of the mystique that insisted that educated women were best fulfilled by living through their husbands and children. She saw this ideology of domesticity as having been greatly revived just after World War II. After

a famous chapter in which she compared the way in which

the “women who live in the image of the feminine mystique

trapped themselves within the narrow walls of their homes”

to the

way in which prisoners learned to “adjust” to concentration

camps, Friedan turned to the alternative. All sorts of scientists of human behavior, she pointed out, had been moving toward a consensus that a basic human need was to grow. It was “man's will to be all that is in him to be.” Her list included Fromm and Riesman, and also a dozen other leaders in psychology, such as Abraham Maslow, Carl Rogers, Gordon Allport, Karen Horney, and Rollo May. Each of these, she said, as well as theologians such as Paul Tillich and many existential philosophers, agreed on the need for the organism to grow to self-realization, or “will to power,” “self-assertion,” dominance,” or “autonomy.”

Friedan recognized better than some of the social scientists that this ideal was not so much established by scienti

f

ic research as it was the postulate on which some promising research was based. But she did take as accepted science “the fact that there is an evolutionary scale or hierarchy of needs in man (and thus in woman), ranging from the needs usually called instincts because they are shared with animals, to needs that come later in human development.” Women were

being blocked from the highest sort of personal growth and development. “Despite the glorification of

âOccupation housewife,

'

” Friedan declared, “if that occupation does not demand, or permit, realization of woman's full abilities, it cannot provide

adequate self-esteem, much less pave the way to a higher level

of self-realization.” In one of the few studies in which these sorts

of categories had even been applied to women, Abraham

Maslow had confirmed that what he called “the high-dominance

woman,” or one who was more akin to men in her attitudes

, “was more psychologically freeâmore autonomous.” By contrast, “the low-dominance woman was not free to be herself, she was other-directed.” High-dominance women, said Maslow, were even better fulfilled sexually than low-dominance women. Riesman had observed that men in mass society needed meaningful work; just the same, said Friedan, applied to women. Enlisting the term that just recently had come into vogue, housewives had lost touch with their true selves and were suffering from an “identity crisis.”

16

Friedan was writing on the eve of America's greatest national identity crisis since the American Revolution itself, and the parallel between the individual and national challenges can be instructive. If many individual American women and men were suffering from identity crises in the 1960s, they could, as Friedan was pointing out, at least turn to a consensus extending from theologians to scientists to pop culture that they should be pursing an ideal of freedom and self-ful

f

illment.

Aside from its later impact on the women's movement, what were the practical implications of this ideal of freedom in the sense of personal autonomy for ordinary Americans?

It is, of course, impossible to measure that in most cases. Perhaps the most practical impact would be the message it sent to young people growing up in any one of the countless American subcommunities. If one were a young person growing up in a Polish Catholic neighborhood in Chicago, in a Jewish community in Brooklyn, or in a small town of the Midwest or the South, the implication of the message was that one should get out from under the petty constraints of local communities and traditions and be true to oneself. One then needed also to avoid the conformity and alienation in the marketplace or the suburbsâsomething that might prove more difficult.

The problem was that freedom is often largely a negative term: “just another word for nothing left to lose,” as Janis Joplin would famously sing shortly before her death in 1970.

17

So if one sought to construct a new identity, the ideal of autonomy did not in itself provide a standard for determining what constituted self-fulfillment. Once one was free from restrictive traditions or expectations, what was going to replace them as a basis for determining what was good for human flourishing? The critics of modernity were warning that one must be vigilant against the demands of hyperorganized commercial society and consumerism lest they undermine one's true humanity. Yet, it was not clear what criteria one should use to determine what the positive alternatives were to the shackles either of traditionalism or of modern conformity.

THREE

Enlightenment's End? Building Without Foundations

The social commentators who identified conformity

as a preeminent modern problem could assume that autonomy was the solution because they were taking for granted that there were better values that authentic, self-fulfilled people

could draw upon. John Dewey, the highly influential philosopher and educator, for instance, had proposed in the 1930s that “a common faith” could be built around self-evident “goods of human association, or arts, and of knowledge.” Dewey presented these ideas as self-evident principles. “We need no external criterion and guarantee for their goodness,” he affirmed. “They are had, they exist as good, and out of them we frame our ideal ends.” Dewey's liberal heirs in the 1950s spoke much the same way, as though there were such common “goods,” which autonomous persons of goodwill could recognize and around which a healthy society might be built.

1

One can better understand the basis for such confidence among the centrist liberal proponents of this outlook by

looking at how they defended itânot against opponents, but against those whom they regarded as heretics. A heretic is not the advocate of an entirely opposing ideology, after all, but an insider, someone who believes that he or she is speaking for the tradition but has come to conclusions that others in the community denounce as unorthodox.

In this case, the heretic was one of the most distinguished sages of the time, Walter Lippmann. His heresy was to say that his liberal colleagues were trying to build a public consensus based on inherited principles, even after they had dynamited the foundations on which those principles had first been established. The result was that liberal culture, of which he was a part, had no adequate shared criteria for determining “the good.” Lippmann's proposed solution seemed to his peers to be much better fitted to the eighteenth century than to advanced twentieth-century thought. The story of what proved to be Lippmann's last book,

Essays in the Public Philosophy

, published in 1955âand the negative reactions of his fellow liberals to that bookâhighlights one of the great unresolved issues of the day.

2

At midcentury, Lippmann had just turned sixty, and he was unquestionably a leading figure in shaping the American liberal consensus. A renowned journalist and author, he was the prototype of the public intellectual. He had grown up in a well-to-do Jewish family, had been educated at Harvard, and had become one of the first Jews to be fully accepted into the cosmopolitan mainstream. While still in his mid-twenties,

in 1914, he had helped to found

The New Republic

, and he had

already published the first two of what would become a score

of influential books. His best-selling 1929 book

A Preface to Morals

was perhaps the volume that best stated the problems inherent in the transition America was undergoing at the timeâthe transition from the moral confidence of the Progressive era to the uncertainties of postwar modernity. Lippmann's fame and influence continued unabated into the era of the Cold Warâin fact, he was the one who had popularized the term “Cold War,” in a 1947 book title. His writings, including countless editorials, were unquestionably among the leading works of the day, setting the agenda for discussions of American democratic civilization and its future.

3

Lippmann signaled by his title,

Essays in the Public Philosophy

, that he would be addressing one of the most important questions of the time: On what philosophical basis might America build a unified public culture, given all its diversity? He began his answer in a prophetic mode, titling his opening section “The Decline of the West,” and recounting the essential twentieth-century political problems that he had been writing about for four decades. From his point of view as “a liberal democrat,” the crucial question of the age was whether “both liberty and democracy can be preserved before the one destroys the other.” The danger was that democratic government would be overwhelmed by mass opinion, which had proved itself incapable of responding rationally to society's rapidly changing needs. Lippmann had already written on this topic eloquently and influentially in the 1920s, and Hitler's popular

support in his rise to power in the 1930s had proven that his fears

were more than justified. “The impulse to escape from freedom, which Erich Fromm has described so well,” Lippmann

wrote, confirmed the broader urgency of addressing the underlying issue.

That deeper issue was the vogue of moral relativism. Specifically, Lippmann was concerned that there were no longer any transcendent moral standards to which to appeal in guiding either the government or the people. In the first half of the twentieth century, there had been a trend to separate the law from reference to any higher moral system. Lippmann had now come to see that as a dangerous innovation. The institutions of free societies, he observed, had been founded “on the postulate that there was a universal order on which all reasonable men were agreed.” In the era of America's founding, even if the more secular thinkers and the traditional Christians may have differed on the exact source of that order and its content, “they did agree that there was a valid law which, whether it was the commandment of God or the reason of things, was transcendent.” Speaking of such essential principles as “freedom of religion and of thought and of speech,” Lippmann affirmed that “the men of the seventeenth and eighteenth century who established these great salutatory rules would certainly have denied that a community could do without a general public philosophy.” But the idea, so essential to establishing democratic institutions, that there was such a higher moral order had not survived modern pluralism, and “with the disappearance of the public philosophyâand of a consensus on the first and last thingsâthere was opened up a great vacuum in the public mind, yawning to be filled.”

The task of building consensus and community, as Lippmann

saw it, was not just a matter of forging agreements on policies

here and there; ultimately, it would rest on underlying philosophical and moral assumptions. One of the effects of pluralism was that morality had come to be thought of as an essentially subjective and private matter. “It became the rule that ideas and principles are privateâwith only subjective relevance and significance,” he wrote. Lippmann saw that same trend in philosophy. Referring to Jean-Paul Sartre's existentialism, Lippmann declared that “if what is good, what is right, what is true, is only what the individual âchooses' to âinvent',

then we are outside the traditions of civility.” With no objective

point of moral reference, with no philosopher to teach people that there was any order or meaning beyond the subjective self, there was nothing with which to counter the madness of the masses or to preempt their madness by educating them in the traditions of civility.

The only hope for reestablishing a public philosophy, and thus for preserving free institutions, said Lippmann, was a recovery of natural law. He asserted this point not so much as a philosophical argument as a philosophical agenda. He did not define natural law beyond referencing an article on it by Mortimer Adler, a Jewish scholar who had long been its chief secular advocate. Nor did Lippmann say precisely how natural

law was to be discovered. Rather, by a recovery of “natural

law,” he meant a return to the conviction that had long been basic to Western thought: that there was some sort of objective moral order or set of timeless moral principles that could be discovered through rational inquiry. The common law and the principles of a free society, he believed, could be sustained only on such a basis. “Except on the premises of this philosophy,” he

declared, “it is impossible to reach intelligible and workable conceptions of popular election, majority rule, representative assemblies, free speech, loyalty, property, corporations and voluntary associates.”

4

Walter Lippmann was, as one of his closest friends said of him, very much “a child of the enlightenment,”

5

and it is helpful to think of him and his project as a public intellectual in that framework. As a quintessential cosmopolitan without strong connections to any ethnic or religious community, he was deeply committed to a universal order of civility. That commitment was in harmony with the outlooks of many of the nation's eighteenth-century philosopher-founders, such as Franklin, Jefferson, and Madison, who wanted to get away from the authority of sectarian subcommunities and to build a larger order on self-evident principles on which people of goodwill ought to agree. In the Progressive era of the early twentieth century, such cosmopolitan outlooks fit the agenda of many of America's leading thinkers who were trying to establish common principles for public life that would transcend local and parochial prejudices. Lippmann studied at Harvard with the famed philosophers William James and George Santayana, and he had been very much in sympathy with the early twentieth-century challenge of how to reconstruct a public philosophy that would meet the demands of the modern age.

The great modern intellectual challenge to establishing a universal philosophy was Darwinism. Prior to Charles Darwin, it had been difficult even for the more secularly minded to imagine a universe that was not the product of an intelligence. Hence, it had seemed likely that humans should be able

to discover some transcendent moral order. Darwin made it plausible to imagine that both the universe and humans themselves were the products of chance natural forces. In that case, moral systems were all human inventions and were best understood by their comparative histories. Added to these theoretical issues was the practical matter that the United States, by the beginning of the twentieth century, was becoming increasingly diverse. How could one reconstruct a common philosophy in such a world?

Walter Lippmann's teacher William James offered constructive principles that might point to a way out. According to James's pragmatism, we can find out which beliefs to hold on to as “true” by seeing which ones prove themselves most effective in getting us into adjustment with the rest of our experiences with reality, including the beliefs we already firmly hold. That is to say, in effect, that rather than descending into relativism or skepticism, we could rely on a sort of survival of the fittest of beliefs, some of which we could accept as true because they have proven to work in the real world.

6

Early in his career, Walter Lippmann adopted an outlook that had a Jamesean hue. “We have to act on what we believe, on half-knowledge, illusion and error,” he wrote in 1913 in his first major book,

A Preface to Politics

. “Experience itself will reveal our mistakes,” he continued. “Research and criticism may convert them into wisdom.” He also, as was common in the Progressive era, had faith that the scientific method could bring people of diverse interests into practical agreement. “The discipline of science,” he wrote in

Drift and Mastery

in 1914, “is the only one that gives any assurance that from the same

set of facts men will come approximately to the same conclusion.” Science was the best hope humanity had in the face of modern pluralism. “And as the modern world can be civilized only by the effort of innumerable people,” Lippmann declared, “we have a right to call science the discipline of democracy.”

7

By the time Lippmann published

A Preface to Morals

in 1929, the confidence of the Western world in scientifically based mastery of human problems had been badly shaken by the disaster of the Great War. The 1920s had become the era of “the disillusion of the intellectuals.” As Lippmann put it, the present was “the first age . . . in the history of mankind when the circumstances of life have conspired with the intellectual habits of the time to render any fixed and authoritative belief incredible to large masses of men.”

Lippmann went on to argue, in contrast to the moralistic platitudes of Protestant theological modernists, that it was time to face frankly the irreversible reality of this breakdown of the old authorities and to reconstruct humanism on a new, secular basis. The fundamental problem for the modern moralist, he declared, “is how mankind, deprived of the great fictions, is to come to terms with the needs which created those fictions.” Still reflecting the spirit of William James, Lippmann was proposing that the constructive moralist should look beneath the varieties of formal systems for the insights into human experience that have been discovered and rediscovered through the ages.

8

Despite the enthusiastic reception of

A Preface to Morals

, by the early 1930s the combination of increasingly skeptical intellectual trends, the Great Depression, and the spread of totalitarianism had made such gentlemanly constructive pragmatism

problematic. In 1929, the same year that

A Preface to Morals

appeared, journalist Joseph Wood Krutch published

The Modern Temper

, in which he argued that evolutionary n

aturalism, if consistently applied, undermined not only traditional religion but also traditional moralities. Supposed moral norms were, after all, nothing more than survival mechanisms

from more primitive times. Evolutionary naturalism, he emphasized, had the necessary implication of undermining all moral authority. Carl Becker, a leading historian of the era, argued for a skeptical pragmatism that anticipated later twentieth-century views regarding moral systems as simply the useful constructions of those who were in power. In his classic 1932 book

The Heavenly City of the Eighteenth Century Philosophers

, Becker maintained that the enlightenment thinkers were really men of faith as much as men of reason. They had an unfounded faith that the universe was the product of a deity and that there were objective natural and moral laws that reason could discover. Their outlook, Becker argued, was thus closer to that of the medieval thinkers of the thirteenth century than it was to that of truly modern thinkers who realized they lived in a chance universe.

9