The Two of Us (2 page)

Authors: Sheila Hancock

I mixed the sand and cement with his huge spade, hollowing out the centre of the heap, pouring in water and flopping the mixture

about ready for Dad to use. We worked in companionable silence, pegging out shapes and heaving the stones about, then sitting

on the front wall with an orange squash admiring our work in progress. My profound love and respect for my father was consolidated

doing that garden. Years later I discovered some soulless fool had demolished it to provide a concrete stand for his Ford

Escort.

1 February

Took delivery of my Jaguar XKR in advance of my birthday.

I’ve christened her Mavis to stop her getting above herself.

Went for trial run. Does she go. ‘Yes, all right, calm down

dear, take it easy,’ But he was beaming. He loves giving

presents.

An Italianate garden may seem a strange choice for a grey suburb of London, but not for Enrico Cameron Hancock. The son of

a man who worked for Thomas Cook, he was born and spent his childhood in Milan. It was rumoured that Enrico Caruso was his

godfather, feasible if Grandfather booked the star’s travel, but I never met my relative to ask him. Where the Cameron, which

I have inherited, came from, heaven only knows. My mother, Ivy Woodward, had worked in a flower shop in Greenwich and a pub

in Lewisham before falling madly in love with my handsome dad and remaining so for the rest of her life. She was a beautiful

girl and made all her own frocks, coats and hats, which were modish copies from magazines. She was clever with her needle.

She made all our clothes too and covers for the furniture and bright curtains to enliven the interior of our box-like house.

She washed all the bed linen and clothes by hand, rubbing them clean on a ridged wash-board. I sometimes turned the handle

of the mangle to wring them dry and then handed up pegs as she hung the clothes out in the garden on Mondays. It was not done

to hang out washing on any other day. The flat irons went on the stove. It was my job to test them with spit. She managed

all this on top of working six days a week at the shop. On the few occasions she sat down for a nap with her eyes closed,

her hands continued to work away with the knitting needles. Dad laid the fire with faggots of twisted paper and chopped wood

for me to light when I got back from school. I cleaned the house from top to bottom on Saturdays, bright-eyed and bushy-tailed

with pleasure when they came home from work and praised me.

Even the presence of my two grannies using our front parlour as a shared bedroom didn’t trouble me, although it must have

been hell for my mum and dad. The two old girls hated each other. Grandma Hancock was ‘piss elegant’ in her moth-eaten fur

tippet and Nanny Louisa ‘Tickle and Squeeze ’er’ Woodward resented her put-on airs. She, after all, had slaved all her life

and saved a few quid while Grandma Hancock had swanned around Europe with Cook’s being the hostess with the mostest and not

a penny to show for it.

They had furious rows over their nightly game of whist that ended with a lot of ‘Who do you bloody well think you are?’ and

‘Don’t speak to me like that, woman.’ It wasn’t helped by Grandma Hancock’s descent into dementia so that she couldn’t remember

which suit was trumps. I loved her childish behaviour, going to the pictures to see the same film over and over and doing

stately dances in the street using a lamp-post as a partner.

3 February

John learning his numbers for

Peter Pan

already. I only

have to play a phrase once and he knows it, he’s got such

a good ear. He’s enjoying himself. Particularly relishes the

phrase ‘Blood will spill, when I kill Peter Pan.’ Have to

remind him it’s a show for kiddie-winkies. ‘Well, that’ll

shut ’em up,’ he says.

Our piano had come with us from the pub and family gatherings always ended with a sing-song. Dad often gave us his Ridice

Pagliacci, reducing us and himself to tears. Then a rousing chorus of his version of the Riff Chorus from ‘The Desert Song’:

Ho so we sing as we are riding ho

Now’s the time you best be hiding low

It means the Ricks are abroad

Go before you’ve bitten the sword.

Mum’s speciality was:

You must remember this

A kiss is still a kiss

A sigh is still a sigh

The world will always welcome lovers

As time goes by.

Her glances towards him were guaranteed to make Dad blush and, of course, cry. He cried at everything, happy or sad. We blamed

his Italian childhood. He laughed till he cried and cried till he laughed. He seldom finished a joke, so convulsed would he

be with the telling of it. The sight of him spluttering and weeping with laughter, doubled up and groaning weakly, ‘Oh Christ’

had my sister and me rolling on the carpet. We also enjoyed it when he got incoherent with sentiment and yet more tears would

cascade into his sodden, overworked cotton handkerchief. Particularly after a few drinks.

Gradually, I warmed to the security of routine in this new way of life in Bexleyheath. I enjoyed playing in the street with

the other kids – no one owned cars then, and I remember no threat of any sort from strange adults or the growing crisis in

Europe, and anyway, I knew my parents would protect me from any harm. At five years old, without fear, I walked the two miles

to school on my own.

At Christmas, a big event pushed my fascination with performing a bit further. Upton Road Junior School decided to mount my

party piece,

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

. It never occurred to me that my teachers would not cast me in the lead. Hadn’t I thrilled the old girls in the Ladies’ Bar

with my winsome Snow White? I knew every line of the role. It was a sad six-year-old who broke the news to her family that

she had been cast as Dopey. Daddy threatened, as he always did, to write a letter, while Mum went into ‘best of a bad job’

mode and set to work with Billie to make me a costume that would outshine all the others. My red dressing-gown had a little

train sewn on, pointy felt slippers were fashioned out of an old mat, and the crowning glory was a cotton-wool beard, fixed

with elastic round my head under a green nightcap. I still felt pretty bitter towards the girl with hair as black as ebony

and skin as white as snow, who squeaked her way through rehearsals of my coveted role. Just because she’s pretty. It’s not

fair. Ah, little girl, it was ever thus. But you will learn that one day her ebony hair will go grey at the roots and her

white skin will crinkle and people will say ‘How sad’, whereas, with a bit of luck they’ll say, ‘She’s perky for her age’

about the woman who played Dopey.

When the great day of the performance dawned, I put on my much-admired costume and set off heigh-hoing up the wooden steps

of the platform behind the other six tiny dwarfs. Somehow my train got caught in my legs and my slippers were well named for

I slid flat on my face. There was a gasp from the audience which I quite enjoyed because it drowned the

sotto voce

Snow White’s line. I straightened myself up, twanging my beard, which had settled round my eyebrows, back in its place. What

was this? A huge, relieved laugh. This is a good lark, no one’s looking at Snow White, particularly when I contrive another

fall and repeat the business with the beard. My lack of subtlety can be traced to this day. Drunk with success, I fell about

all over the stage, to the delight of the audience and the fury of my teacher. Not to mention Snow White’s mother. A triumph

rescued from the ashes of my humiliation. A lesson learnt. Making people laugh was a good ploy to deflect attention from Snow

Whites.

4 February

Letter from someone asking me to support a campaign

against the closure of Upland Junior School. Because it is

an old building and to save money it is being amalgamated

with another school. They wouldn’t do that to Eton.

For some reason, I hope unconnected with this event, I was moved to another school, Upland Junior, and here, under the guidance

of an inspirational headmistress, Miss Markham, I developed my performing skills. Participation was the teaching method employed

here, probably to grab the interest of the fifty-plus kids in each class. We acted everything, even geography – I was Japan

and my best friend, Brenda Barry, was Singapore. In history, being tall, I got pretty good at playing kings and was a dashing

Hannibal, thoroughly enjoying trampling over several small Alps. In science, Brenda, as the earth, did a pretty nifty revolve

round my sun and our eclipse was a triumph. The only mild anxiety in my life was whether, in the playground, I would be last

to be chosen in ‘The Farmer’s in His Den’. ‘Ee, aye, ante oh, we all pat the dog’ could be pretty scary. Even worse, ‘We all

gnaw the bone’. They were golden days with only small childhood fears.

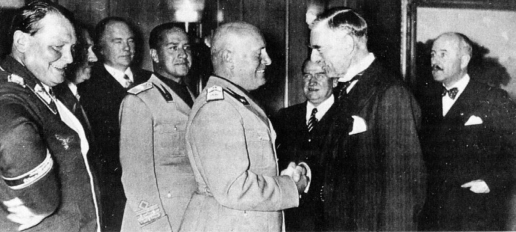

The adults, meantime, must have been terrified. The Nazis had entered the Rhineland and Austria. In 1938 a deal had been struck

by Chamberlain to give them the Sudetenland in return for ‘Peace in our Time’. Chamberlain was a man who, like my parents,

had experienced the lunacy of the 1914–18 war, and it is understandable that he tried every trick in the book to appease Hitler.

His despairing cry, ‘I am a man of peace to the depths of my soul. Armed conflict between nations is a nightmare to me’, reveals

his anguish. I have a photo of him in stiff collar and cravat, watch-chain draped across his waistcoat, with two sceptical

sober suited Englishmen behind him. He is shaking hands politely with a bullet-headed, ludicrously uniformed Mussolini, backed

by a posturing Daladier and Goering similarly attired for a musical comedy. A gentleman at sea with a group of thugs. Yet

the likes of my Dad in those days trusted their leaders to save them. They knew best, the upper crust. They were educated

and knew what’s what.

5 February

Meeting in the flat at Number 10 to discuss luvvies’ (God

how I hate that word) involvement in the election campaign.

I found myself having a go at Tony Blair: ‘You surround

yourself with men in Armani suits, and the man people

elected is submerged in spin. They wanted your honesty,

your raw idealism, etc., etc. Why are you running this

campaign for the

Daily Mail

?’ I went on about prisons –

‘Have you ever visited one?’ – and the vilification of asylum

seekers. Was appalled by Hague’s speech in Harrogate

saying Labour will leave Britain ‘a foreign land’. Shades of

Enoch Powell. Why hasn’t he denounced such language? I

couldn’t stop. I could hear myself ranting, it was awful.

The woman from

Coronation Street

said, ‘I don’t know

why you’re ’ere.’ Then others came to my defence and the

whole meeting was soured. Blair was rattled but then so

am I. Don’t think he is used to people disagreeing with

him. I like him and especially Cherie but when in power

people seem to shed their ideals and are only interested in

staying there. He pointed out no Labour Government had

had a second term so I suppose he has to watch what he

says. But it’s sad. Get me. Silly actress telling off the Prime

Minister. Mummy would be horrified. My Quaker friends

would be pleased though: ‘Speak truth to power.’ Went

home and told John, ‘There goes your knighthood, pet.’

The days of the polite politics of Baldwin, Ramsay MacDonald and Chamberlain were about to collapse in the face of the savagery

to come and with them my peripatetic but carefree childhood.

In February 1939 people in Latham Road began to take delivery of Anderson air-raid shelters, but not my father. Was he still

clinging to a belief that sanity would prevail? He knew the SS had ordered the destruction of Jewish properties in November

1938, and some Germans, probably in fear of their lives, had watched while their neighbours were beaten up.

Kristallnacht

must have convinced most people that this was some evil force that had got out of hand and become very dangerous. Not my dad.

A scrupulously honest, loyal and compassionate man, maybe he just didn’t believe it could be true. When Hitler entered Prague

in March he did nothing. Only when they invaded Poland and Russia in September did he dig a hole in the garden. Too late to

get the corrugated iron panels to complete an Anderson shelter, he managed to acquire some railway sleepers to cover the hole.

On 3 September 1939 we gathered round our wireless to hear Chamberlain’s weary admission that in response to his ultimatum

that Hitler should retreat from Poland, ‘No such undertaking has been received. Therefore this country is at war with Germany.’