The Underground Reporters (9 page)

“How much longer can this go on?” John’s mother asked one evening, as she listened to Czech-language news from Great Britain on the shortwave radio. The Czech radio station was in the hands of the Nazis, of course, but the British translated the news into all the languages of Europe, to tell people the truth, and reveal Hitler’s lies.

John’s father nodded. “The news from other countries isn’t good. But at least we’re all together here, and still in our own home, even if we do have to share it. Think of the families who have had to leave their homes in Poland and Germany, and move into the ghettos.”

“That could never happen here, could it?” Mother asked. Father didn’t answer. “But what about money?” she continued. “At this rate, our savings will be gone in no time. Then what will we live on?”

“We have to get used to eating less,” he replied. “Less meat, and bread with no butter.” He saw the look in his wife’s eyes and added quickly, “Just for now. I’ll work again soon. I’m sure of it.”

John turned away. He hated to see his father out of work and his mother so unhappy. But he didn’t want to think about war, and worse things happening in other countries. Surely there would never be ghettos in

Budejovice! Even though certain places were forbidden to Jews, John could still walk on the street and play with his friends. Although the rules restricting Jewish families were increasing, the war didn’t scare him. He was young and spirited, and he wanted to play sports with his friends. He even had a job to do every day.

His job was to deliver messages to the city’s Jewish families. He rode his bicycle from home to home, leaving a notice with each household. The notice instructed the families to list all of their properties and belongings for the Nazi authorities. They were ordered to write everything down: how many rings, bracelets, or pieces of silver they owned; how much land was theirs; the name and value of their business.

It had never occurred to John that, by collecting information about Jewish families, he was in fact helping the Nazis. “Don’t you realize that you are helping to deliver this information into the hands of the enemy?” asked Beda one day, as John stopped by Beda’s house.

The last thing he wanted was to collaborate with the enemy. But it was true that he had been told to do this work by the Kile, the Jewish council – and the Kile’s orders came from the Nazis. Still, John had to continue his job. He tried to make the best of it. He even sang songs to himself as he rode door to door. But before long, his dilemma was over. His bicycle, like everything else, had to be turned over to the Nazis.

Now it was time for John and the other children to return to school. Fall was approaching, and soon it would be too cold to go to the swimming hole. Even though regular school was forbidden to Jewish children, it

was important for them to have some way to continue their education. And so, in September, they began classes with Mr. Frisch.

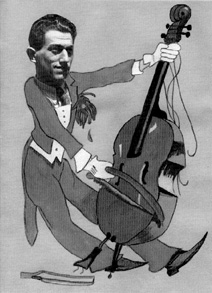

Mr. Joseph frisch, the teacher (an image from

Klepy

).

Joseph Frisch’s family had a coal business in town. He was a talented young Jewish man who, in his spare time, played bass in the town orchestra. He was also studying to be a teacher. When school was no longer permitted for Jewish children in Budejovice, Mr. Frisch arranged for groups of children to come to his home for lessons.

The classes were small, only five to six children at a time. School started early, at about eight o’clock in the morning, and continued until about two o’clock in the afternoon. Children between the ages of eight and thirteen attended this school five days a week, and were taught by Mr. Frisch as well as some older boys and girls who were there to help.

Mr. Frisch was happy to have this opportunity to continue to teach. He had set up small desks in his living room so that the children could feel as if they were really in school. And the lessons were difficult. The children studied algebra, Latin, history, and grammar. They had assignments to do after school and homework on weekends.

The first time John entered Mr. Frisch’s home, he spotted Tulina

sitting at another desk.

At least having her here will make things more interesting,

he thought. As he glanced around the room, he was happy to see Beda there as well.

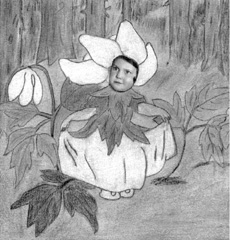

John’s first girlfriend, Tulina (Rita Holzer), from

Klepy.

There in Mr. Frisch’s living room, the children were even able to continue their religious education. Rabbi Ferda came once a week to teach Hebrew and Jewish studies. Before the war, most of these young students had not received as much Jewish education as they were now receiving. There was no more hope of skipping classes.

Sometimes, Rabbi Ferda could be gloomy about the future. “Our fate through the ages is like a red thread of danger, weaving its way through time,” he preached. Whatever did he mean by that, wondered John. Of course times were tough. But surely things would get better, and the war would end soon. I

can’t wait for that to happen,

he thought.

And I can’t wait to get out of this class!

Secretly, he longed for each day to end.

CHAPTER

12

T

HE

R

EPORTING

T

EAM

In those early fall days of 1940, when John and his friends had returned to school, one of the few things they had to keep them connected was

Klepy.

The newspaper was doing what Ruda had hoped. It was serving as a link for the Jewish children of Budejovice, the one place where their thoughts and ideas could come together and be shared with everyone else. It was even more important now that they could no longer meet at the swimming hole. John and his friends read the stories from the newspaper aloud to one another, and then looked forward to the next edition.

On October 6, 1940, the fourth edition of the magazine was produced. By now,

Klepy

had a beautiful color cover, drawn by a young artist who went by the name of Ramona. Ramona was really Karli Hirsch, who was now one of the editors, in charge of the drawings. His pictures were becoming a main feature of

Klepy.

Often, he took real photographs of young people in Budejovice, and added his own illustrations, transforming these photos into lively cartoons and comic strips. And how the magazine had grown! The fourth edition was eight pages long, and included a sports column, poetry, and detective stories.

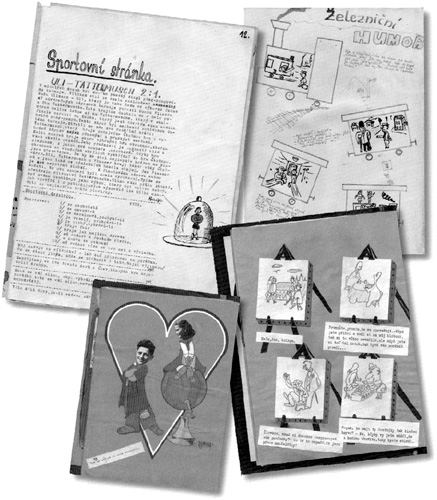

Clockwise from top left

:

Klepy

regularly included drawings, stories, a sports report, comics, and a humor section. This sports column lists the ten rules of sportsmanship. The humor page has jokes about trains, and the comic strip also includes jokes and riddles. Bottom left: Karel Freund (left) and his girlfriend, Suzie Kopperl. The caption reads, “You are the only one in the world.”

The reporting team was also growing. Rudi and Jiri Furth had been part of the editorial group from the beginning. Reina Neubauer was beginning to write poems for the paper. Dascha Holzer, Tulina’s sister, wrote stories, along with Suzie Kopperl. Suzie was the girlfriend of Karel Freund. She had already written several poems for

Klepy,

including one about Karel. Other writers, like Jan Flusser and Arnos Kulka, regularly contributed to the newspaper.

Ruda knew that

Klepy

was an important lifeline for the Jewish youth of Budejovice, as well as the whole Jewish community. It was important to him personally as well. When he worked on

Klepy,

he could almost overcome the shadows over his life. But keeping it going week after week and month after month was hard work. He began each day by going to work at the candy factory. Irena brought him lunch there, often rushing from her own work as a seamstress to bring food to her younger brother. When his workday ended, he met with Jiri, Karli, and the other writers to work on

Klepy.

They were very careful to finish their meetings before the curfew for Jews began at eight o’clock in the evening. But sometimes a few of them worked into the late hours of the night, and then snuck home through the darkened streets, wary of the patrolling Nazi soldiers.

Usually, they all met at Ruda’s apartment to organize the newspaper. He had his typewriter and whatever paper and other supplies were available. When those ran out, they pooled the little money they had to buy more paper and pencils. Luckily, Jewish people were still able to shop in certain stores at certain times of the day.

“What are we going to write about this month?” Ruda asked his reporters, as they sat around the table in his family’s small flat, planning the fifth edition. One bright light burned above their heads, casting dark shadows across their intent faces. Together they pored over the poems, drawings, and jokes that had been submitted. Sometimes, they read the stories aloud to one another, eager for someone else’s opinion, or unsure about exactly where to place the story. “These stories are fun,” said Ruda thoughtfully, as he listened to Jiri Firth reading one. “But I think we need to write about serious issues as well.” Ruda believed that, in addition to being entertaining,

Klepy

could also become a forum where important ideas were discussed.

“We must be careful,” countered Reina Neubauer. “We don’t want the Nazis to find out too much about us. If they think this is a political magazine, they might shut us down.” Reina was a serious-minded young man who loved to write stories. Before the war began, he had often helped his sister with her writing assignments. As a result, Frances had often received high grades that she had not quite earned on her own.

The reporters looked over the articles for that edition and sorted out their tasks. Ruda always wrote the editorial; that was his job as the creator of

Klepy.

“We need another editorial that encourages people to write contributions for us,” said Dascha Holzer. She was a bright, self-assured girl with a wild head of curly, brown hair.

Ruda nodded and sat down at the typewriter. “To all readers,” he wrote. “Obviously your contributions have diminished. We understand that the swimming season is over. Therefore, interest in our paper may have gone down. However, we must keep

Klepy

going.” He sat back, satisfied with his opening.