The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945 (110 page)

Authors: Adam Roberts,Vaughan Lowe,Jennifer Welsh,Dominik Zaum

The institutionalization of hostility towards private force might make the regulation of the complex world of private security more difficult. When actors pose a threat to international peace and security, or to territorial integrity, it makes sense to ensure that they are regulated. In other words, it makes sense to regulate private force on the basis of what private fighters do, not on their status as private fighters. One way to do this is to set out strict rules about when and how private fighters can be hired. Given that PSCs have actively sought regulation and are currently employed by many states around the world, it seems counterproductive to work from the starting point that PSCs are mercenaries and that there is something inherently problematic with actors who sell military services. The genie of private force is firmly out of the bottle, and treating the decision of many states, NGOs, and even the UN itself to use private force as an incidence of mercenarism will do nothing to regulate the situation. Persisting in treating these actors as mercenaries will only serve to alienate them.

A statement from PSCs is appended to the final (2005) Special Rapporteur’s report. In the statement, PSCs argue:

in light of the fact that PSCs are frequently employed by UN member states and the UN own [sic] entities, we strongly recommend that the UN re-examine the relevance of the term ‘mercenary’. This derogatory term is completely unacceptable and is too often used to describe fully legal and legitimate companies engaged in vital support operations for humanitarian peace and stability operations.

52

There is no question, however, that as PMCs and PSCs have the capacity to use lethal force, some regulation ought to be in place which deals with such agents, and the UN ought to be the starting point for regulation of an internationally active industry providing military and security services. The current approach of the United Nations Working Group on Mercenaries is, however, more likely to alienate these companies, which themselves advocate regulation, than it is to bring them into a regulatory framework which will benefit the international system.

The institutionalized hostility towards mercenaries in the General Assembly and its related bodies has had a direct impact upon the range of choices available to the Security Council. If mercenaries have not been as dangerous as the GA response would lead us to believe, does this mean that private force might be a useful tool for the SC? It has been suggested that PMCs could ‘fill a void’ left by problems with UN peacekeeping,

53

and it has been widely recognized that the private force option might be cheaper than peacekeeping,

54

and that in some circumstances (particularly where conventional aid no longer works, where intervention by states is politically or economically impossible, or situations where aggressive peace-enforcement is required) private force might provide better or more feasible assistance than a UN mission.

55

Indeed, Brian Urquhart has argued that the UN could be well served by private assistance during peacekeeping missions.

56

However, although officials inside the UN and commentators outside it have recognized that private military force might play a useful role, either replacing or complementing existing UN peacekeeping missions in a combat capacity, they firmly indicate that it is unlikely ever to happen.

Interviews with UN officials indicate that the negative image of mercenaries reflected by the GA would prevent the UN from ever using private force in a peacekeeping capacity, no matter how useful it might be. David Harland, the chief

of the Best Practices Unit in the Department of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) believes that the potential use of private military companies faces a very serious obstacle in the form of political liabilities created by the negative images of mercenaries.

57

Michael Møller, the Director of the Executive Office of the Secretary-General, believes that the stigma of mercenaries, arising from their image as ‘roughnecks’ interested only in ‘greed and profit’, would make it impossible for PMCs to be used in a peacekeeping context, even though their staff might be superior to some of the peacekeeping contingents currently provided to the UN.

58

While UN officials can see the merits of private force privately, they believe that member states’ dislike of mercenaries would prevent the option from ever being seriously mooted.

59

The only exception to this dislike appears to be the use of private security forces, in a strictly non-combat capacity, to assist the UN in humanitarian tasks or to train state militaries as part of security sector reform. However, even when private force is used in these less controversial roles, UN officials are reluctant to speak openly about it. When asked about the use of PMCs in peacekeeping during a press conference, Kofi Annan ‘bristled’

60

at the suggestion that the UN would ever consider working with the companies, saying ‘first of all, I don’t know how one makes a distinction between respectable and non-respectable mercenaries.’ Annan went on to remark that he was not aware that he had made any statements implying that he would accept the use of mercenaries in tasks associated with peacekeeping, but that he had looked at ‘the possibility of bringing in other elements – not necessarily troops from governments – who might be able to provide security, assist the aid workers in the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and protect them’ when no aid from governments was forthcoming to separate armed fighters from refugees on the Rwanda-Zaire border.

61

The Secretary-General reiterated these remarks in the Ditchley Foundation lecture, which he delivered in 1998, pointing out that

Some have even suggested that private security firms, like the one which recently helped restore the elected President to power in Sierra Leone, might play a role in providing the United Nations with the rapid reaction capacity it needs. When we had need of skilled soldiers to separate fighters from refugees in the Rwandan refugee camps in Goma, I even considered the possibility of engaging a private firm. But the world may not be ready to privatize peace.

62

Member states undoubtedly disapprove of the idea that private forces might be used in UN peace operations. It is said that many ‘member states and staff at the UN take the view that PMCs are immoral organisations, who have traditionally served autocratic and unpopular governments and whose operations are littered with human rights abuses. There is also a perception amongst staff and Member States from the Third World that they are also inherently racist.

63

Institutionalized dislike of private force within the General Assembly and among member states thus constrains the Security Council by closing off a potential course of action.

ONCLUSION

To conclude, it is helpful to answer the questions posed at the beginning. The Security Council has had minimal interaction with private force because private force has rarely had a significant impact on international peace and security; and the General Assembly has had a much stronger reaction in part for normative reasons. The GA has taken a strong moral position which closely associates the use of mercenaries with a threat to national self-determination. This has caused the Assembly and some of its associated bodies to perceive mercenaries, PMCs, and PSCs as far more threatening than they really were and perhaps are. In terms of what this difference in approach

means

, it seems clear that the strongly institutionalized hostility towards private force within the General Assembly constrains the Security Council. The hostility towards mercenaries engendered by the GA, and its equal discomfort with PMCs and PSCs has, for the moment, closed the doors on the use of private force by the SC. The GA has the capacity to shape international opinion on an issue in a way which limits the Council’s freedom of action. Moreover, a history of hostility has alienated the private security industry and perhaps made the UN a less likely venue for regulation of the world of private force today.

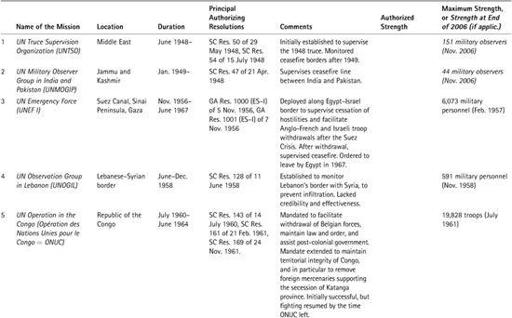

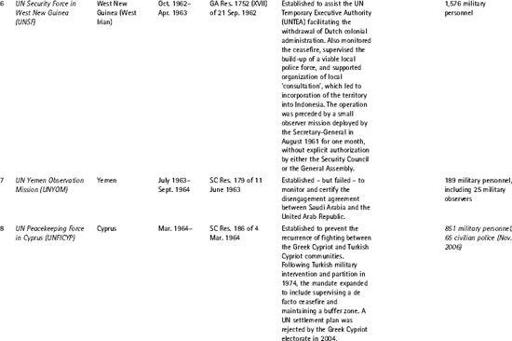

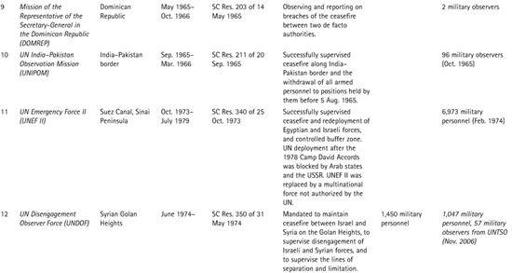

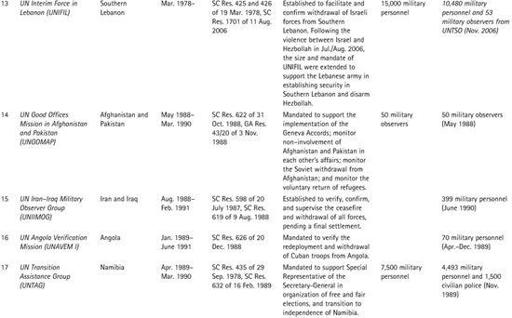

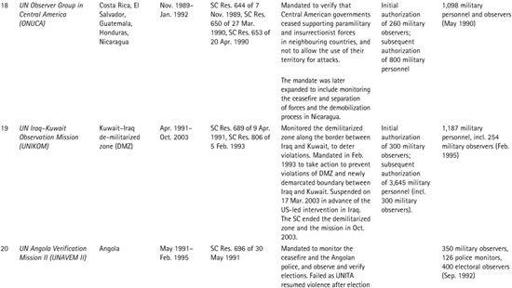

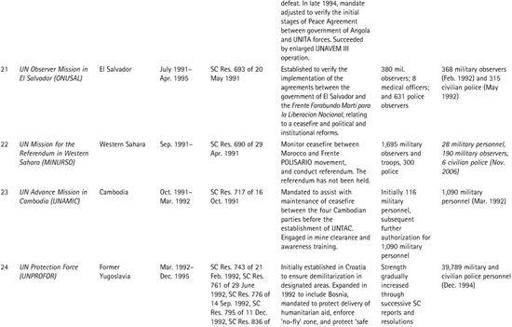

This is a chronological list of all the bodies that have been classified by the UN Secretariat as UN peacekeeping operations. All of them were authorized by a principal organ of the UN – mostly the Security Council, but in a few cases the General Assembly. All of them have been under UN command and control. They have normally been financed collectively through assessed contributions to the UN peacekeeping budget. Their functions have included peacekeeping, peace-enforcement, observation in a conflict, and post-conflict peace-building. For certain other peacekeeping activities linked to the UN, see

Appendices 2

and

3

.