The United Nations Security Council and War:The Evolution of Thought and Practice since 1945 (89 page)

Authors: Adam Roberts,Vaughan Lowe,Jennifer Welsh,Dominik Zaum

YSTEMIC

C

HANGES

B

EARING ON

UN (N

ON-

), I

NVOLVEMENT

Changes in the international system could make UN interventions more (or less) likely. In the early 1990s there was talk of a ‘New International Order’. The close of the Cold War, it was held, had liberated the Security Council from vetoes cast for ‘zero-sum’ reasons by antagonistic powers, while the 1991 liberation of Kuwait demonstrated the potential of UN-authorized action. UN prestige was further boosted by the contribution of its more traditional diplomacy to the settlement – or apparent settlement – of such long-running problems as Namibia, Cambodia, Angola, and El Salvador. Malone writes of an ‘era of euphoria’ lasting roughly from the end of the first Gulf War until ‘the failure to deploy successfully the UN mission in Haiti… a week after the deaths of U.S. Army Rangers in Somalia had seriously undermined … UNOSOM II’. During this period, 15 new peacekeeping operations were launched, as compared with 17 in the previous 46 years.

51

The UN would set the world to rights, backed, and where necessary impelled, by the now manifest hyper-power, the United States. This vision was, as events in the former Yugoslavia showed, unrealistic even at the time, and it soon faded.

For one thing, the US was not disposed to ‘bear any burden, pay any price’ in contexts where its interests were not involved, and where there was often no clear-cut issue of right and wrong to galvanize it. Having gone into Somalia to relieve famine and sort out a failed state, the US exited once things became less simple and it started taking casualties. This was an unusually rapid volte-face, but the history of the Vietnam and Korean wars (and very possibly of the Iraq occupation) emphasizes US difficulties in sustaining domestic support for lengthy and peripheral commitments that involve casualties without clear-cut achievements. But even were US commitment greater, one cannot assume that the UN will always be available to give effect to American purposes. For though there is, at present, no real disposition in the world outside the UN to embark on traditional balancing against the dominant power, within the Security Council the veto makes this both feasible and safe. For here, the US is no more than first among equals. Yet unless the UN can draw on US resources, there are fairly low limits to the military operations it can undertake.

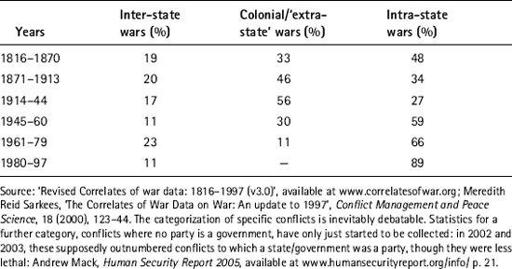

Over time, the nature of conflicts has been changing in a way that might prima facie have been expected to make UN intervention less likely. On one calculation, the number (though not the intensity) of conflicts can be divided between ‘interstate’, colonial (‘extra-state’), and ‘intra-state’ as shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Nature of wars, 1816–1997 (shown by percentage share)

The UN was originally established to deal with 1930s-style cross-border aggression. With the advent of an Afro-Asian majority, the concern with decolonization was heightened: in 1960, the General Assembly noted that ‘the increasing conflicts resulting from the denial of’ freedom to dependent peoples ‘constitute a serious threat to world peace’, and declared that ‘[i]nadequacy of… preparedness should never serve as a pretext for delaying independence.’

52

However, UN involvement in purely domestic conflicts (which now dwarf ‘inter-state’ wars in both numbers and casualties) is inhibited by the Charter, which makes clear in Article 2(7) that it does not authorize UN intervention ‘in matters which are essentially within the jurisdiction of any state’. In reality, such involvement now represents the commonest kind of UN operation. For there have been important changes in attitudes towards host-government consent.

Host-government consent is formally required for the deployment of UN peacekeeping missions or the like. Often it is simply out of the question: Russia would never admit a UN peacekeeping force to Chechnya, nor India to Kashmir; and China (with its Security Council veto) is very cautious about authorizing intrusive UN activity that might constitute a precedent in relation to Tibet.

Weaker states, however, can sometimes be leant on (as Turkey regularly was in the nineteenth century). In 2006, Sudan was being pressed, though, at the time of writing, without success, to allow a more capable UN force to take over from the African Union in Darfur. Very occasionally, too, the requirement of host-government consent has simply been overridden, notably in Haiti. Here, following ineffective sanctions, the UN in 1994 authorized an invasion to displace the de facto power-holders and reinstall the elected President they had driven out. However, President Aristide proved a disappointment and, when rebellion erupted in 2004, the UN authorized new forces (UNMIH, followed by MINUSTAH) to usher (Aristide says compel) him out of the country, and then held the field until elections in 2006.

Often, however, UN involvement is not merely accepted, but actively sought by the local parties. The closing stages of civil wars now frequently give rise to a new genre of activity – ‘peace-building’ – to which the UN is well equipped to contribute. Kissinger argued in 1982 that ‘[c]ivil wars almost without exception end in victory or defeat… [I]t is next to impossible to think of a civil war that [genuinely] ended in coalition government.’

53

Kissinger exaggerated – Colombia’s

violencia

was ended (or at least much reduced) by the 1958 agreement that for twelve years the Presidency should alternate between the Liberal and Conservative parties. Even so, conflicts like Vietnam were of the winner-take-all variety; and one cannot readily imagine, say, Lenin and Kolchak joining in a power-sharing administration with a view to League of Nations-supervised elections. However, over the last decade and a half such ‘peace processes’, while far from universally successful, have become not uncommon.

Specific cases vary. But one can speak of a paradigmatic sequence of: a ‘peace accord’ negotiated (often under external pressure) between the parties to a conflict, followed by ceasefire/s; a transitional government, often involving power-sharing and buttressed by a UN or other external force to disarm and help reintegrate former combatants; assistance in the return of refugees; and the conduct of internationally supervised elections. Thus following brief fighting (with some foreign involvement) in Guinea-Bissau, Security Council resolution 1216 welcomed agreements signed in Praia, Abuja, and Lomé, and called on the government and the rival military junta to ‘implement fully’ their provisions, including

the ceasefire, the urgent establishment of a government of national unity, the holding of… elections no later than… March 1999,… the withdrawal of all foreign troops… and the simultaneous deployment of the interposition force… (ECOMOG) of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS).

54

Such a paradigm can proceed without UN involvement. In Lebanon, it was the Arab League that brought the parties together and ‘sister Syria’ that then enforced

submission to the new government (while maintaining a general proconsular presence). In Northern Ireland, negotiation was essentially between the British and Irish governments, on the one hand, and the local parties and paramilitaries on the other, with some US mediation and some external monitoring, but no UN participation. More commonly, there is a symbiosis between the UN and the major regional actors.

Despite its copious recent use of

Chapter VII

language,

55

the UN has been reluctant to put its forces in harm’s way by crossing the ‘Mogadishu Line’ and operating without at least the broad consent of the local warring parties. It prefers not to intervene until after the contestants have been induced, whether by negotiation or compulsion, to stop fighting. As the

Annual Register

commented on Burundi in 2001, the ‘absence of a cease-fire precluded the United Nations from assisting in the implementation of the [largely Ugandan, South African, and Tanzanian brokered Arusha] peace accord’.

56

Instead, the UN limited itself to blessing the efforts of South African and other peacekeepers. Then, years later, with a final peace agreement seemingly within reach, the UN Mission in Burundi took over the African Union’s peacekeeping mission, AMIB.

57

Or, as a joint UN-ECOWAS document put it:

Increasing demands for the rapid deployment of peacekeeping forces in the aftermath of intra-state conflict has [sic] confronted the United Nations with a requirement it has not been able to meet with in an acceptable timeframe…[This] has given rise to a reliance on others to bridge the gap…[with UN peacekeepers subsequently taking over from regional forces]…in Sierra Leone,… East Timor, …Liberia, …Côte d’Ivoire, …Haiti, …[and] Burundi.

58

SSESSING

UN N

ON

-I

NVOLVEMENT AND

I

NVOLVEMENT

The UN, of course, touches international affairs at many points. Focusing on the Security Council, it can be seen that, while some pronouncements (notably Resolution 242) have helped mould the terms of debate on major issues or, like Resolutions 211 and 598 (calling respectively for Indo-Pakistani and Iran–Iraq ceasefires), afforded a golden bridge across which one of the belligerents could retire, many others have been ignored with impunity when that seemed better to

suit national interests. Beyond this, the Council has mounted two major exercises in coercion, over Korea and the liberation of Kuwait. In both, though more especially the latter, the US found UN backing very useful, though in the first case it would certainly, and in the second very possibly, have acted without it. These apart, most UN operations have either sought to separate former combatants, or to consolidate and develop ‘peace-building’ processes that owe more to the prior actions of other states and alliances. All are valuable functions, but essentially the Security Council is a niche player that states use chiefly to handle conflicts (admittedly often tragic ones) seen as relatively peripheral.

People differ in assessing past UN operations (listed in

Appendices 1

–

3

) and, correspondingly, in their views of what the UN could or should undertake in the future. On the critical side it is contended that, whatever their humanitarian merits, some interventions have preserved rather than resolved problems. For example, in its first decade the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus did indeed protect the Turkish minorities in Cyprus, but only by ghetto-izing them, leaving the island’s underlying problems unchanged until Turkey seized an opportunity to intervene in 1974. In a provocative article, Edward Luttwak expands such criticisms into a condemnation per se of peacekeeping interventions and of most refugee relief.

59

War, Luttwak holds, ‘can resolve political conflicts and lead to peace’, but only ‘when all belligerents become exhausted or when one wins decisively’. But since ‘the establishment of the United Nations…, wars among lesser powers have rarely been allowed to run their natural course’. Thus the 1948 imposition of ceasefires during the Arab–Israeli war had the perverse effect of enabling the parties to regroup, rearm, and continue fighting. Externally imposed armistices ‘freeze conflict and perpetuate a state of war… by shielding the weaker side from the consequences of refusing to make concessions for peace’. Perhaps over-pessimistically, Luttwak gives the 1995 Dayton accords as a prime example: they ‘condemned Bosnia to remain divided into three rival armed camps… Since no side is threatened by defeat…, none has a sufficient incentive to negotiate a lasting settlement;… [instead] the dominant priority is to prepare for future war rather than to reconstruct devastated economies and ravaged societies.’ Further:

the first priority of U.N. peacekeeping contingents is to avoid casualties among their own personnel. Unit commanders therefore habitually appease the locally stronger force … Peacekeepers chary of violence are also unable effectively to protect civilians … At best, U. N. peacekeeping forces have been passive spectators to outrages and massacres, as in Bosnia and Rwanda; at worst, they collaborate with it, as Dutch U.N. troops did in… Srebrenica by helping the Bosnian Serbs separate the men of military age from the rest of the population. The very presence of U.N. forces, meanwhile, inhibits the normal remedy of endangered civilians, which is to escape from the combat zone. Deluded into thinking that they will be protected, civilians … remain in place until it is too late to flee.

Indeed, during the siege of Sarajevo, the UN, ‘in obedience to a cease-ire agreement with the locally dominant Bosnian Serbs’, ‘inspected outgoing lights to prevent the escape of… civilians’.

‘Humanitarian relief’, Luttwak continues, can prove even worse. The United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) ‘turned escaping civilians into lifelong refugees, who gave birth to refugee children’ and grandchildren, while the ‘concentration of Palestinians in the camps…has facilitated the…enlistment of refugee youths by armed organisations’. Had each European war ‘been attended by its own post-war UNRWA, today’s Europe would be filled with … camps for millions of descendants of up-rooted Gallo-Romans, abandoned Vandals, … – not to speak of more recent refugee nations such as the [three million] post-1945 Sudeten Germans [and their seven million Silesian counterparts] …It…would have led to permanent instability and violence.’ Among developing nations, NGO provision of relief exceeds ‘what is locally available to non-refugees. The consequences are entirely predictable…refugee camps along the…Congo’s border with Rwanda…sustain a Hutu nation that would otherwise have been dispersed,…providing a base for…Tutsi-killing raids across the border’, and (one might add) the occasion for the Rwandan invasions of the Congo that set off one of the most damaging wars in the past decade. For such reasons, Luttwak concludes, ‘[i]t might be best for all parties to [stand aloof and] let minor wars burn themselves out.’