The Unknown Warrior (18 page)

Read The Unknown Warrior Online

Authors: Richard Osgood

Chris Daniell has put forward another interesting possibility for the presence of weapon injuries â trial by combat. Between 1985 and 1986, York Archaeological Trust excavated the site of St Andrew's Church, Fishergate, York, and uncovered 402 articulated skeletons of which 29, all male, showed evidence of weapon trauma. Some of these skeletons, as we have seen, may relate to the Battle of Fulford in 1066 â double burials in graves, with weapon injuries, and with the strong likelihood of a single violent event. Others cannot be explained away by one large single episode of combat and, as they occurred over a period of time from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, must have a different cause. As trial by combat was known for the Medieval period this would certainly be a plausible explanation (Daniell, 2001).

These caveats notwithstanding, some of the human remains that have been excavated belonged, indisputably, to those who fell in combat, most notably those found in the mass graves from Towton and Visby.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 7

⦠there was a great conflict, which began with the rising of the sun, and lasted until the tenth hour of the night, so great was the boldness of the men who never heeded the possibility of a miserable death. Of the enemy who fled, great numbers were drowned in the river near the town of Tadcaster, eight miles from York, because they themselves had broken the bridge to cut our passage that way so that none could pass, and a great part of the rest who got away who gathered in the said town and city were slain, and so many dead bodies were seen to cover an area six miles long by three broad and about four furlongs.

(George Neville, Bishop of Exeter, in Boardman, 2000: 15)

On 29 March 1461 one of the bloodiest battles of the dynastic Wars of the Roses took place in the small village of Towton in North Yorkshire. Fought in a blizzard, the Yorkists eventually broke the Lancastrian armies and put the fleeing to the sword. Chroniclers refer to some 28,000 casualties numbered by the heralds (

ibid.

: 15). It was a most bloody engagement and one which was to prove decisive in this phase of the wars; Edward, Duke of York, was crowned King Edward IV later that year.

Some 535 years later, ground preparation for a new garage at Towton Hall was to provoke a macabre discovery. Human bones were unearthed and, as a result, an archaeological investigation of the vicinity took place. What followed was one of the most interesting archaeological discoveries of battlefield remains (Fiorato, 2000: 2). A rectangular mass burial pit was uncovered with tightly packed bodies generally orientated in an eastâ west/westâeast axis in prone or supine positions (Sutherland, 2000a: 41) (see Plate 13). These bodies were then covered in a mound of soil. Analysis has shown that the bodies were of rugged males â and the skeletal remains represented thirty-seven or thirty-eight individuals (Boylston

et al.

, 2000: 45).

On closer examination the true horror of the wounds suffered by these men became clear. Thirteen men (33 per cent) had post-cranial wounds; there were thirty-seven sharp injury wounds and six blunt weapon wounds, mostly to the hands and arms. This wound pattern is consistent with âparrying a blow from an assailant' (Novak, 2000a: 91). The majority of these were also to the right arm or hand, indicating the right-handed attributes of the sufferer. As these wounds seem absent from the torso of the deceased, perhaps they were afforded good body protection â padded armour or brigadine (

ibid.

: 93â4).

Shannon Novak's analysis (2000a) is important in drawing a fuller picture of the men. For example, nine of the soldiers had well-healed cranial trauma wounds from previous battles or conflicts. This set of sixteen separate wounds ranged from minor superficial nicks to deeper flesh wounds.

âTowton 16' had suffered a truly dreadful facial injury with a section of bone sliced from the lower jaw with subsequent fracture. This, though scarring, had successfully healed â perhaps revealing a better quality of medical care than we often attribute to this period. The man was thus a true veteran â some 46â50 years of age. Would he have inspired confidence in his younger brothers-in-arms, who perhaps faced such brutal conflict for the first time? His luck finally ran out as he sustained eight blade, blunt and puncture wounds in his death at Towton (Novak, 2000a: 95; Novak, 2000b: 246â7). The wounds found here were caused by arrows, swords, war-hammers and pole arms. Arrow wounds might be expected for those killed in the mass flight of arrows in early stages of battle, but they were relatively rare and the evidence seems to point towards the killing of these men in a violent episode towards the end of the battle, perhaps the rout of the fleeing Lancastrian forces. Other trauma also illustrates the most basic of human emotions â fear. There is enough evidence of damage to teeth to suggest that clenching of teeth in a situation of extreme stress occurred (Knüsel and Boylston, 2000: 178).

The infantryman catalogued as âTowton 41' was another individual who had had prior experience of warfare (see Colour Plates 8 and 9). In addition to the wounds that caused his death at Towton, he had a series of scars that had been inflicted beforehand, some of which had healed. On his skull was a small depression fracture of the frontal bone, an old fracture by the left eye, along with a v-shaped 39mm-long blade injury that had cut the top of the man's head to a depth of 4mm, and a well-healed adjacent depression. An examination of his skeleton by Knüsel (2000: 109â11) revealed the traits of development that suggested he was experienced at using the bow â like âTowton 16', the man was a veteran.

During the battle, Towton 41 suffered dramatic and fatal injuries. Shallow blade wounds were present on the front of the man's face, on the left-hand side. He also had a blade wound to the left frontal bone of the skull and a small depression fracture close by. These wounds were inflicted from the front, presumably in face-to-face combat. In addition to these blade wounds some other severe injuries were noted that had been inflicted from behind. The man's right hand, arm and leg were cut deeply and there was a further blade wound to his spine. A 46mm segment of bone was removed by a blade to the upper left part of the skull just above the mastoid process (for an analysis of this individual, see Novak 2000b: 262â4; see figs 35 and 36).

Three small square perforations were located on the top rear (posterior parietals) of the skull ranging from 7 to 8mm in size, encircled by a bevelled margin. Again these wounds were inflicted from behind and above, and seem to correspond with the top spike of a poleaxe (

ibid.

: 263). All in all, Towton 41 had thirteen cranial wounds and nine other wounds â both those inflicted in the encounter that led to his death and others from earlier engagements.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 7

Towton 41: an infantryman from the mass burial at Towton, 29 March 1461, probably an archer of the defeated Lancastrian army

This is the body of a man aged between 26 and 35 years. The body, orientated north-west/south-east was of an individual 172.5 ± 2.99cm in height (Holst

et al.

, 2000: 208) who, in similar fashion to many who had ended up in the burial pit at Towton, had lived a rugged lifestyle as indicated by the presence of Schmorl's nodes (

ibid.

: 208).

This man was not new to combat, displaying both old wounds and physiological traits consistent with him practising archery over many years. He had wounds both to the front and inflicted from behind, perhaps indicating a degree of frenzy in dispatching a wounded man. His location in the mass burial pit, far from the supposed centre of the battlefield, and the types and specific location of his wounds, may all point to him having been killed in the rout of the Lancastrian forces.

UNKNOWN WARRIOR 8

ANNO DOMINI MCCCLXI FERIA III POST JACOBI ANTE PORTAS VISBY IN MANIBUS DANORUM CECIDERUNT GUTENSES HIC SEPULTI. PRO EIS

The battle was fought outside the gates of Visby, between Danes and Gotlanders, in the year 1361, on 27 July, and the victory went to the attacking foreign army.

(Thordeman, 2001: 1â2)

As recorded on the later battlefield cross, in 1361 an army of Danish regulars fighting for King Waldemar Atterdag appeared before the gates of Visby on the island of Gotland. The forces arrayed against the Danes were no match â the old and the young, the sick and disabled, all were pressed into service of the town and none had the training of their opponents. According to contemporary Swedish chronicles, some 2,000 townspeople were killed (

ibid.

: 23). Waldemar entered the town in triumph while the bodies of the slain lay around putrefying for days in the heat before being cast into great burial pits. Visby fell to the Danes.

On 22 May 1905, during the excavations of an arbour, several human skulls covered by mail were discovered. By early July, the whole of a mass grave was exposed and the first of the victims from the Battle of Visby some 544 years before was found. In 1912, as part of the preparations for a road, further remains were found over a wide area, and more excavations took place in the 1920s and in 1930 (

ibid.

: 56â60).

Several stories were connected with these archaeological excavations. Supposedly, âthough the flesh had disappeared from the bones and grinning skulls of these warriors during the six centuries since they fell for their country, the moist earth had become so saturated with the decay that only men with abnormally tough nerves could endure the overpowering odour that rose from the excavation'. Indeed the archaeologist, Dr Wennersten, âcould not work in the pit without fainting' (

ibid.

: 87). While the 1912 excavations took place an illustrious visitor arrived: Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. Prophetically, Dr Wennersten was alleged to have greeted the Kaiser: âHere you see, Your Majesty, how frightful are the consequences of war. I hope you will remember!' (

ibid.

: 88). As we shall see in Chapter 7, the results of the Kaiser's battles were also to create their own archaeological record.

What had been found, and excavated in a grid system, were five mass graves (three main graves) with Common Grave 1 being some 5.5m wide and 7m long, and 1.5â2m deep (skeletal material being 0.5â1m thick). Common Grave 2 was 12m long, 6m wide and 2m deep with 0.5m thickness of bone. Although the archaeological technique of the time meant that remains were excavated by grid rather than by individual skeleton (the technique successfully adopted at Towton), the excavators felt confident enough to make several observations about the men found. They believed that Grave 1 held between 258 and 268 individuals, Grave 2 some 710â98, and Grave 3 had 119 people. Graves 4 and 5 had a large enough quantity of victims to realise a total of up to 1,572 deceased. Perhaps it is safe to suggest that those in the mass graves represented the town's defeated peasant army rather than Waldemar's dead for whom greater respect would have been shown, as the victors and holders of the field.

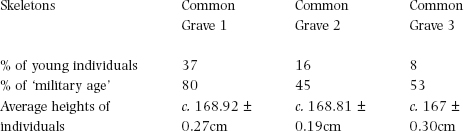

The filling of the graves was subject to some sort of deliberate spatial patterning, with large discrepancies between the number of young individuals and those of military age. Dominant wound types varied, with more cuts to the extremities of the bodies present in Common Grave 3.

Ingelmark (2001: 152) was unable to reassemble the skeletons recovered from the excavations. Initial examinations indicated that there might be nine female pelvises within the mass graves, but this was something that the author was uncertain of on later analysis. It is hoped that current work under the aegis of Professor During (pers. comm.) might be able to provide more information.

Table 4.2.

Comparison of skeleton details within the graves

Source

: after Thordeman (2001: 80).

What is beyond doubt is the range of wounds to the men in the mass graves. The results of attack by sword, axe, crossbow, morning star, mace, lance and even â as with Towton â war hammer, can be witnessed (Ingelmark, 2001: 160). Cutting weapons, such as swords and axes, had caused some 456 wounds, while arrow wounds were present in 126 cases, 60 of which also had cuts. One tibia even retained the arrowhead as the body was thrown into the pit (Thordeman, 2001: fig. 167); skulls retained crossbow bolts that perhaps preceded the main assault (

ibid.

: figs 179â81). A further astonishing example of leg wounds is that of a man whose lower legs were cut off âprobably by a single blow' (Ingelmark, 2001: 164â5).

Several of the wounds might indicate that, alongside infantry, there were a number of mounted troops â damage to the unprotected lower legs of the men being a vital clue. One such body had had the right foot severed from the lower leg by a cut through both tibia and fibula. Indeed, a large quantity of wounds seems to have been âaimed vertico-horizontally from below' (

ibid.

: 177). These wounds may also reflect damage inflicted upon a wounded, prone foe â as per those in the grave pit of Towton.

Although much of the armour used by the town's forces might have been outmoded by the standards of 1361, mail coifs were still capable of preventing some wounds â only 40 per cent of wounds were to the skull. Nonetheless, some skulls do still show injuries â in Grave 1, 42.3 per cent of the bodies had cuts on the cranium. Grave 2 had a total of 52.3 per cent of skulls with wounds, though in Grave 3, only 5.4 per cent of the skulls were damaged â perhaps as a result of better head protection worn by those thrown here.