The Urchin of the Riding Stars (15 page)

Read The Urchin of the Riding Stars Online

Authors: M. I. McAllister

Tags: #The Mistmantle Chronicles

“Shouldn’t be too difficult, sir,” said Urchin, and wondered why he’d ever doubted Padra.

“And now, about young Scufflen,” said Padra.

“I understand, sir,” said Urchin. “There was nothing you could do. But it wasn’t just any baby hedgehog, it was Scufflen, and Needle loved him.”

“Would you like to hold him?” asked Padra.

It didn’t make sense. I’m definitely not well, thought Urchin. I must have banged my head. But the hedgehog in the rocking chair stood up, still smiling down at the bundle in her arms. Not sure what was happening, or even whether he was properly awake, Urchin held out his paws. He looked down into the solemn, sleeping face of a baby hedgehog with milk around its mouth. It hiccupped.

It was a very small baby, wearing a tiny white robe that looked as if it had been made of scraps from the workroom floor. Lifting a corner of the blanket, Urchin saw the curled paw.

“Scufflen!” he whispered. The baby yawned enormously, showing a milky tongue.

“I’ll find him a nest now,” said the hedgehog, taking him back.

Urchin gazed at Padra with new admiration.

“You saved him!” he said.

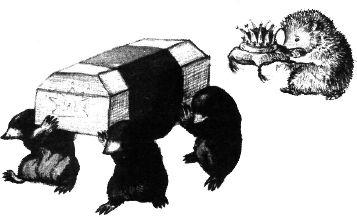

Mother Huggen carried Scufflen to the nests. The mole was settling the baby squirrel to sleep, and another squirrel had joined the young ones playing on the floor. Urchin’s heart lifted and brightened.

“This,” said Padra, “is the most secret place on all the island. You didn’t know I was a nursemaid, did you?”

“Do you rescue them all, and bring them here?” asked Urchin eagerly. “All the babies to be culled?”

“Not all,” said Padra. “I can’t save them all. Husk gets to them quickly. And some of the frail ones don’t survive, but at least they’re well looked after while they do live. This morning I was about to send you to find Scufflen, but you’d already done it. You told Lugg where he was, so Lugg sneaked into Husk’s chamber through a mole hole, dragged the baby away, and brought him here. Can you guess what this place is?”

It was underground, in the roots. But it must be a very ancient tree, to have such complicated, spreading roots, and so strong. The ceiling was arched and vaulted with the stretching roots. The fireplace was wide and built in stone, with a mantelpiece, and in one wall was a sturdy wooden door.

“It can’t be the Old Palace!” cried Urchin, and gazed about. “It’s real, and I’m in it?”

“The ancient mole palace—yes, Urchin, it is,” said Padra. “Did you believe it existed?”

“I always hoped it did,” said Urchin.

“Most animals think it’s only a legend, and we let them go on thinking it,” said Padra. “Those of us who know aren’t allowed to tell anyone else where it is, or even that we know. There’s Mother Huggen here, and Moth the mole.” The mole maid waved a paw at Urchin. “She’s Lugg’s daughter. Arran knows, and Fir, of course. He’s allowed to pass the secret on, and he told Crispin and me years ago. Husk always suspected that we knew where it was, and I’m sure he’s tried to find it. When you’re recovered, I’ll teach you the routes to it. We bring the babies’ mothers here to see them, but they have to be blindfolded, and of course they keep everything secret.”

“But the babies can’t stay here forever,” said Urchin. “What happens when they get older?”

Mother Huggen hurried to rescue a small hedgehog that was getting a little too close to the washing.

“This one’s nearsighted,” she explained as she turned the little hedgehog around. It trundled away with determination and bumped into the log basket, but didn’t seem to mind. “I send him to play with the moles. They’re all nearsighted, so they teach him how to get along.”

“You’re right, Urchin, they can’t stay here,” said Padra. “As soon as they start to talk, we move them out. They soon forget about being here.”

“I make them little mitts to fit over any bad paws or anything of that sort,” said Huggen. “They look just like real paws; you wouldn’t know. And we train them well, so nobody can see anything the matter with them.”

“But where do they go?” asked Urchin.

“Mostly to colonies on the north or west of the island, well away from the tower, or in the middle of the wood,” said Padra. “Places where nobody will ask questions about one or two extra young ones, and the parents know where they are. But I wish we didn’t have to do this. There’s something very wrong about this island, Urchin. There shouldn’t be any culling at all.”

He walked to the fire, carefully stepping over a baby squirrel, and stoked the blaze. Urchin limped painfully toward him.

“This isn’t the only quiet backwater colony on the island,” went on Padra. “There are groups of animals here and there, mostly near the shores or in the caves by the waterfall, living quiet lives and keeping away from the tower as much as they can. That’s apart from the host of hedgehogs and moles digging for jewels, who work so hard they must have forgotten what daylight is like. You didn’t know I have a younger brother, did you? Fingal. He lives in a small otter colony, about as far away from Husk and the tower as I can get him.”

“Quite right, too,” said Mother Huggen. “Fingal’s safer that way.”

“Everybody’s safer that way,” said Padra. The nearsighted hedgehog was now climbing in and out of tree roots. When it met a mole head on, it curled into a ball in shock.

Padra threw another log on the fire, and sparks showered upward. “It’s worse since Crispin went,” he said. “The king listened to him. No wonder Husk wanted him out.”

“Crispin!” said Urchin, remembering. He hobbled painfully back to the moss bed and scrabbled at the hem of his cloak.

“I was coming to show you, sir!” he cried. “I was putting the robes away, and I found these in the chest!”

The leaves were battered now, with bits broken away from the edges. But the mark was still visible.

“Crispin’s mark!” exclaimed Padra, his eyes bright and keen. “Where did you find these?” He stood turning the leaves in his paw as Urchin answered.

“Have you ever seen a captain give a token, Urchin?” asked Padra.

“No, sir,” said Urchin, “but I saw the king once mark a leaf for Husk.”

“I’m sure he did,” said Padra drily. “Captains don’t use tokens much these days. Husk gets Gloss the mole to carry messages for him. I like to give my orders myself, if I give them at all. But if Crispin wanted to confirm that an order was from him, or give his approval of something, he’d send a leaf with his mark on it as a token. What you’ve found here may just be some old tokens.”

“Oh,” said Urchin, disappointed. “So they’re not important, then?”

“I think they’re very important,” said Padra. “They may be just a few old tokens, but Crispin wouldn’t have left them in the robe chest. Somebody must have collected them for a purpose.”

“Or Husk got hold of one, and made copies of it,” suggested Urchin.

“So,” said Padra, “on the day when we drew lots…Urchin, I must have seaweed where my brain should be! Why didn’t I see it before? I’ve always known that Husk tricked us that day, but I couldn’t see how. He didn’t take Crispin’s token out of the bag at all—he must have hidden one of these in his paw.”

“Or tucked it into his sleeve,” said Urchin in excitement. “We—I mean, someone—should have checked which tokens were still in the bag.”

“And we would have found Crispin’s,” said Padra.

“So these are evidence that Husk did it!” said Urchin eagerly. “If we take these to the king…”

“Slow down, Urchin,” said Padra. “What can we prove? Husk would only say that they were old tokens Crispin left lying around, or that we copied them ourselves to incriminate him. The king and the Circle would listen to him, not us. We have to wait until Husk goes too far. He will, believe me. The animals will lose faith in him, and be ready to listen to us. Then we can move against him, and these leaves will help us to do that. But we still have to wait for the tide to turn.”

“But he gets worse all the time!” said Urchin. “He’s even talking about rationing the winter food! Can’t we

help

the tide to turn?”

“Oh, yes, we can do that,” said Padra cheerfully, “but we have to do it cautiously. If Husk thinks we’re stirring up rebellion, believe me, he’ll have us murdered on the quiet. Me, Arran, Lugg…even you, Urchin.”

Urchin was about to say that he was willing to take the risk, but Padra stopped him.

“Yes, I’m sure you’re willing to die for the island, but you’re more use alive,” he said. “We all are. Without us, there’d be nobody left to protect the others. When I show up Husk, it has to be in public, at a big, special occasion. He wouldn’t be able to do any quiet knife-in-the-back stuff with the whole island watching.”

“Like at a feast, sir?” said Urchin. “The next one’s the Spring Festival.”

Padra smiled. “Yes,” he said thoughtfully. “I was thinking of the Spring Festival.”

“Shh!”

said Huggen, and Padra sprang to his feet with his paw on his sword hilt. Something was moving toward them through the tunnels. Urchin stepped back from the entrance, flexing his claws. But then Padra relaxed, and let go of the sword.

“Arran,” he said. “I know her step.”

“Ask her to marry you, why don’t you?” muttered Mother Huggen.

“She’d only hit me,” said Padra.

Arran appeared presently, loping on all fours as she emerged from a tunnel.

“Padra, you’re on next watch with the king,” she said.

“Stay here tonight, Urchin, and I’ll get you out tomorrow,” said Padra. “If anyone asks, I’ll say you were so useless you didn’t know which floor you were on, and that’s why you fell out of the window. On your head, so no harm done. I’ll tell Fir the truth, though. He ought to know everything you’ve told me. And, Urchin, those leaves could be vital. You’ve done bravely today. But don’t put yourself in danger. I told Crispin I’d take care of you.”

“I’m too old to be taken care of,” said Urchin as Padra left. But it was good to be here, with the flickering fire and Mother Huggen bringing him hot drinks and creamy hazelnut porridge, and Moth hushing a baby. The small hedgehog half woke up, found its way to Urchin’s lap, and fell asleep again.

“We all need to be taken care of,” said Mother Huggen. “This island is full of young animals Captain Padra has rescued. Arran, will you stop and have some cordial with us? And it’s time you asked Padra to marry you.”

“He’d only laugh,” said Arran.

Urchin wondered what Padra would do at the Spring Festival. But filled with hot porridge and warmed by the fire, he could no longer keep his eyes open. He was drifting into dreams. He managed to slur a prayer for Crispin, but he was already more asleep than awake.

LEANER WAS CRYING

LEANER WAS CRYING

.

She was hunched miserably in a small chair in a corner of Husk and Lady Aspen’s chambers. It was a hard and uncomfortable chair, a good place for misery. She was not used to being snapped at and hadn’t deserved it, so she sniffed in a corner out of the way, where somebody was sure to find her. Two mole maids came in carrying black mourning veils, and she drew a paw across her eyes.

“Still crying for the queen?” asked one of the moles.

“I think the captain was a bit sharp with her just now,” said the other. The moles didn’t like Gleaner, who had become Lady Aspen’s darling so quickly, but Captain Husk had been bad-tempered with everyone since the queen died. It was time his wife knew about it.

“I didn’t mean any harm,” said Gleaner. “I knew there should be flowers by the coffin and I’d been out in the snow and ice to find something pretty, and I told him so, and he turned and shouted at me for nothing!”

“Shouted at you?” said a mole eagerly.

“Yes, he shouted that I was to stay away and leave him alone,” she sniffed.

Lady Aspen glided into the room.

“My poor little Gleaner!” she said. “Still weeping for the queen?”

“Captain Husk was cross with her,” said the moles, and exchanged sly smiles. Either Gleaner or Captain Husk would be in trouble. They didn’t care which.

“You may go,” said Aspen, and the moles curtsied and scurried away. “Never mind, Gleaner. Captain Husk has too much on his mind just now, and the whole island depends on him. Did the moles bring the veils?”