The Urchin of the Riding Stars (30 page)

Read The Urchin of the Riding Stars Online

Authors: M. I. McAllister

Tags: #The Mistmantle Chronicles

The little mole maid bustled across the rocks toward him. She looked pleased with herself.

“Moth,” he called. “Are all the young ones safe?”

“Oh, yes!” she said confidently. “But we’re not very comfortable stuck under that boat, especially with our prisoner. She takes up a lot of room.”

“Prisoner?” said Padra.

“Yes, sir, would you like to come and see? And please will you tell us what to do with her?”

A few strong animals helped Padra overturn the boat, and Mother Huggen seized the paws of any infants likely to run away. Basins and plates had been tipped across the floor, and somebody had spilled porridge.

“Heart love us,” said Padra. “It’s Tay!”

From the sand, Tay glared up at him with all the dignity she had left. It wasn’t much. She had been tied and trussed with whatever Mother Huggen could find—knitting wool, thick trails of seaweed, and, of course, Moth’s apron. A fluffy pink blanket had been stuffed between her teeth and fastened as a gag. There was porridge in her fur.

“She’s been a lot of trouble,” said Mother Huggen severely, as if Tay were a very naughty child. “She’s been thrashing about in a tantrum and knocked over all the basins and spilled the porridge—that’s why we had to tie her up so much. I’d be most grateful if you’d take her off my paws, Captain Padra.”

Padra turned to his helpers. “Mistress Tay,” he said, “is a distinguished otter, a scholar, and a lawyer, and came near to being made a captain. Treat her with respect. Untie her, use another upturned boat for a prison cell, and guard her well. When we take the tower, she’ll be escorted to a cell there.”

He bowed low, hiding the twitching of his whiskers. “Mistress Tay, I’m sorry for this indignity,” he said. “But I suspect you have brought it on yourself.” Then he bowed abruptly to Huggen and Moth, and strode away before they could see him laughing.

“I suppose the little ones can go home now,” said Needle, left with Mother Huggen. “Nobody’s going to cull them now.”

“So that’s that,” said Huggen. “No more secret nursery. No more babies. Home. And quite right, too.”

“I’ve lost Hope,” said Moth suddenly.

“There’s no need for that, my dear!” said Huggen.

“No,” said Moth, “I mean

him!

Hope! All the rest of them are accounted for, but not Hope the hedgehog!”

“Oh, bless him,” sighed Huggen. “What can we do with him? No doubt he’s gone off looking for Thripple, his ‘beautiful mother,’as he calls her.”

“I know her!” said Needle. “But I don’t know where she is.”

“Goodness only knows,” said Huggen. “And he’s not safe to be out on his own!”

“He can do tunnels,” said Moth.

“He still bumps into walls,” grumbled Huggen. “We’ll have to start a search. But I daresay he’ll be all right. There’s something about that one. The Heart protects the helpless, I suppose.”

In the bare Gathering Chamber, daylight was fading. Aspen sent Gleaner to light the lamps.

“And take a message to all those at guard duty,” she said. “Tell them Captain Husk and I are proud of them. There are fewer of us now, but that means a greater share of treasure. Have food and wine sent to them.”

“Yes, my lady,” said Gleaner. “Please, my lady…”

“Yes, Gleaner?” said Aspen.

“It’s all Padra’s fault, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Gleaner.”

Gleaner trotted importantly away, trying to glide as gracefully as Aspen. It was Padra’s fault. If he’d just let Husk take over, none of this would have happened.

Aspen turned to Husk with an impatient swish of her robe.

“Why don’t we just kill the king now?” she asked.

“Because then we’d lose everything,” snapped Husk. “Padra would storm the tower.”

“What if he does?” she said. “We’d win.”

“We might not,” said Husk. The king was sagging in his arms, and he pushed him roughly up against the window. “Stand up, you. Our losses in the battle were greater than we expected. Granite should have finished Padra off; then they wouldn’t have a leader. They should all have done as I said, all along. I’ve always said that. It’s true.”

He stared down at the shore. The tide was coming in. Padra’s supporters had camped high, away from the shoreline, close to the tower. None of this would have happened if everyone had simply done as he wanted. He knew best.

He was the first son of his family, or at least, the first son who mattered. There had been a feeble brother who had died at birth, and a feebler one who had managed to live. But he had never been of any use. He was an embarrassment to the family and the colony. Husk had tried to explain that to his parents, but they wouldn’t listen; so it had been up to him to push the miserable cripple over a cliff.

Killing the priest would be satisfying, but it was too unlucky. Besides, he would want Brother Fir to crown him. The priest would come to his senses.

There was a tap at the door. Aspen drew the small dagger she had fastened at her waist.

“Can I come in?” said Gleaner’s voice, and presently she hurried in with a basket on her arm. “I brought some food.”

“Thank you, Gleaner,” said Aspen, replacing the dagger. “And, Gleaner, the king can’t reach his flask. He may want a drink from it now and again,”

“Yes, my lady,” said Gleaner. She took the flask and held it to the king’s lips. Whatever was in it, it didn’t smell as strong as the spirits Aspen had been giving him, but she didn’t like to mention it. She was frightened of Captain Husk.

“Does he never sleep?” said Padra. Looking up through the gathering twilight, he could see Husk still holding the king at the open window, still with the knife at his throat. Padra had stationed groups of animals at points all around the tower and the island, but he himself had stayed with Arran and a few others before the Gathering Chamber windows. By the campfire light, their faces were warm and fierce.

Pulling his cloak around him, Padra massaged his painful shoulder and walked around the tower until he stood under Fir’s turret. The small, bent figure stood framed in light in the arch of a window.

“Brother Fir!” called Padra, and saw the priest’s head tilt toward him.

“Dearest Padra!” called Fir. It was too dark to see him clearly, but Padra heard his smile. “I have prayed for you. Dear son, stand firm.”

“Do you have all you need?” called Padra. “Do they treat you well?”

“I have the company of four excellent moles,” replied Fir. “They are here to make sure that I don’t leap from windows, nor take up a sword against them. Four of them, Padra! With weapons! Two in here, and two at the door! They must think me a most formidable warrior; I’m thoroughly flattered. And I have bread and water, which is all…my goodness! There’s a star! A riding star!”

“It can’t be!” Padra turned to look as a spark of silver flew across the sky. “But you always tell us when we’re going to have riding stars!”

“Hm,” said Fir. “Well, this time I didn’t, because I didn’t know. Extraordinary!”

For good or for harm, thought Padra, thinking of Crispin and all that had happened since the last night of riding stars.

Good or harm?

He knelt on the cold rock.

“May I have your blessing, Brother Fir?” he asked. And however old Fir was, however weary, the paw he lifted in blessing was firm and did not tremble. He turned his face to the skies.

The night grew colder. Stars flocked, danced, stopped, and began again. The besiegers slept in snatches. Padra slipped into a rock pool to ease his injuries in salt water. Husk muttered to himself, to the king, to Aspen. All watched the stars. And Fir, standing at his window, looked beyond the riding stars and saw the first pale gold light tracing across the eastern sky. With a great leap of his heart and a surge of joy, he saw in the distance the faraway specks of Mistmantle’s deliverance.

RCHIN KNELT IN FEATHERS, STRETCHING FORWARD

RCHIN KNELT IN FEATHERS, STRETCHING FORWARD

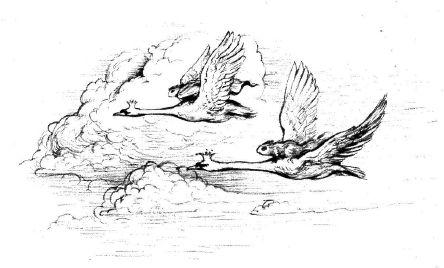

as he held tight to the strong, white neck of the swan. The rush of cold air through his fur chilled him, but his legs were warm, pressed against the swan’s body. He gazed forward and upward past its head, into the sky, not daring to look down.

They were flying higher. The beat and beat and beat of the powerful white wings swished in the air as they rose.

“I’m flying!” Urchin told himself again, breathless, his eyes wide. “I’m really flying!” It was wonderful and impossible, but it was happening.

Crispin flew ahead of him, his head up, his hind paws anchored in the space between the wings. For Urchin, if there was one thing better than flying back to Mistmantle, it was flying back with Crispin—and Crispin was himself again.

He wondered at the strength and endurance of the birds. The swans had told him how noble they were, and how they were not birds of burden to carry lesser animals, but for once, only once, for Crispin’s sake, they would do this. For hour upon hour they had flown, as the night sky clouded and the air seemed dense around them.

“It’s the mist!” Crispin had cried. “We’re going home!”

“Wonderful swans!” called Urchin. “Beautiful, wonderful swans!”

He didn’t know if they could hear, and swans didn’t care about the praises of a common tree-rat. But he had to say it. Mists curled around them. White wings rose and fell, rose and fell.