The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (12 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

Shortly after Max Schlesinger moved to London in 1852, he already understood that ‘Among the middle classes...the omnibus stands immediately after [fresh] air, tea, and flannel, in the list of necessaries of life.’ Omnibuses by that date appeared to have always been part of the life of the city, but they were an innovation of only two decades’ standing. Until the mid-1830s, the short-stagecoach, often referred to as the short-stage, had been the main method of transportation between suburbs and centre. These coaches were similar to the stagecoaches that made longer journeys across country (see pp. 90–101), but tended to be the older, smaller and less comfortable models. By 1825, London had 418 short-stagecoaches making over a thousand journeys daily, transporting the residents of Kilburn, or Bayswater, or Paddington, to and from the centre. Dickens’ fiction teems with characters using the short-stage: in

Pickwick Papers

, set in the late 1820s, Mrs Bardell and her friends go from Pentonville ‘in quest of a Hampstead stage’ in order to take tea at the famous Spaniards Inn on Hampstead Heath. In

David Copperfield

, Agnes takes the stage from Highgate to Putney, and then from Putney to Covent Garden. In

Great Expectations

, Pip takes the stage to Hammersmith from Barnard’s Inn, where he was lodging in Holborn; Estella travels to Richmond by the City short-stage.

The short-stages were notoriously unreliable. In Dickens’ very first published short story, ‘A Dinner at Poplar Walk’, Mr Minns gets into a coach ‘on the solemn assurance...that the vehicle would start in three minutes’. After a quarter of an hour, Mr Minns leans out the window and asks when they are going to start: ‘“Di-rectly, sir,” said the coachman, with his hands in his pockets, looking as much unlike a man in a hurry as possible.’ Dickens’ readers must have laughed ruefully. Twenty years earlier, Louis Simond had lamented his experience on the short-stage from Richmond to the West End: ‘We stopped more than twenty times on the road’ and it took two hours to cover seven or eight miles.

Yet they also offered a convenient and personal service. After dinner at Mr Minns’ friend’s house, ‘as it was a very wet night’ the nine o’clock stage comes by to see if anybody wanted to go to town. This was no fictional device. In the 1820s, the driver of the short-stage for a neighbourhood such as Peckham proceeded along his route each morning, house by house, picking up his regulars, and if they were not ready he waited. (Mr Minns, not being a regular, does not get the same courtesy and the coachman drives off, saying Mr Minns can ‘run round’ and meet him at the inn.) When the coaches arrived at their destinations, passengers told the coachman whether or not he should wait for them on his return trip in the afternoon. The short-stage, starting late in the mornings and returning early to the suburbs, was of no use to working men, but suited their employers, whose office hours were much shorter; the class of passenger was reflected in the price, with many suburban journeys costing 2s.

In 1828, a mourning-coachbuilder named George Shillibeer saw omnibuses on a visit to Paris and thought they might work in London. He shipped one over and had it running by December, but it was the following summer before there was a regular service, which ran from Paddington Green to the Bank, pulled by three horses harnessed abreast, and carrying twenty-two passengers.

34

(It was no coincidence that this first bus route was

along the New Road, one of the earliest of the arteries to free itself from the turnpikes.) The buses were an immediate success: they averaged six miles an hour and the fare for the route swiftly dropped from 1s to 6d, a quarter of the cost of the short-stage. The original French three-horse buses were too wide and too clumsy for London – two could not pass each other at Temple Bar, while at St Paul’s nothing could pass a bus, not even the narrowest cab – and they were quickly replaced by smaller buses, pulled by two horses. All the buses had names: some, like the Bayswater, were known by their destinations, but most were named for the famous, or the legendary – the Nelson, for example, or the Waterloo, or the Atlas – while a few were named for their owners. The

Times

omnibus was owned by the newspaper, and the Bardell belonged to the Bardell omnibus company.

Inside, there were twelve seats, with another two beside the coachman (a few models had four, but this was rare). These box seats were for favoured regulars, who tipped the driver to ensure that places were kept for them. When they arrived, depending on which seat was empty, the cad shouted ‘near side’ or ‘off side’, and the driver offered the passenger the end of a leather strap. Grasping it with one hand, and a handle on the side of the bus with the other, the passenger put his foot on the wheel and then swung himself up, using a single step halfway between the wheel and the driver’s footboard to mount the box. When the box passengers were ready to dismount, the driver banged with his whip on the board behind his head to alert the cad, who collected the fares from the passengers as they left.

From 1849, there was also seating on top of the bus, reached by a set of iron rungs at the back, which led to a knifeboard, a T-shaped bench where passengers sat back-to-back, facing outwards (see Plate 2). The outside was the preserve of men: no woman in skirts could have managed the ascent to the seat beside the driver, and even if their clothing had permitted them to climb the iron rungs to the top – and there was no rail to hold on to on the way up, only a leather strap – once they were aloft there were no panels along the side, so their legs would have been exposed to passers-by below. The inside was low-roofed, and so narrow ‘that the knees of the passengers, near the door, almost effectually prevent their comrades from entering and departing’. Straw was laid on the floor, to keep out the damp and cold, but

it was ineffective, and usually filthy. In the 1850s, the ladders were replaced by a little iron staircase and what were called decency boards were placed along the length of the roof. After that, said one Frenchman appalled by the ‘narrow, rickety, jolting, dusty and extremely dirty’ interiors, no one rode inside ‘if there is an inch of space unoccupied outside; women, children, even old people, fight to gain access to the top’.

The driver surveyed the world from his perch, wearing a white top hat, ‘a blue, white-spotted cravat, with a corresponding display of very clean shirt-collar, coat of dark green cloth...his boots well polished...There is...an easy familiar carelessness...a strange mixture of

hauteur

and condescension, as much as to say: “You may keep your hats on, gentlemen.”’ According to Alfred Bennett, at least in the 1850s, the drivers always wore a rose in their buttonholes, too. In the rain, they shared with the box-seat passengers a leather covering that went over their laps, while the remaining ‘outsides’, as the passengers on the top deck were known, took shelter under their own umbrellas.

The buses devastated the short-stage business. By 1834, the number of short-stagecoaches had fallen by a quarter, to 293, matched by 232 buses. By 1849, buses ran from London Bridge to Paddington, and from the old coaching inn, the White Horse Cellar in Piccadilly, to Fulham; the New Conveyance Office in Paddington had an hourly bus service leaving from coaching inns on the New Road and Oxford Street, and from the Bank via Oxford Street among others. At first they were no more for the working classes than the short-stages had been, as none ran first thing in the morning: until the early 1850s, no bus reached the City before 9.30. They were, said the

Penny Magazine

in 1837, for those ‘whose incomes vary from £150 to £400 or £600 and whose business does not require their presence till nine or ten in the mornings, and who can leave it at five or six in the evening’. But soon their popularity meant that routes from the suburbs started earlier and ran later, as well as more frequently. In 1856–7 the London General Omnibus Company, an amalgam of many of the early companies, carried 37.5 million passengers, and Gracechurch Street, equidistant between the Bank and London Bridge in the City, had become a hub for buses running south of the river to the suburbs.

The stops were then, as they had been for the stagecoaches before them, at a series of inns. In their sometimes days-long journeys, stagecoaches had stopped at coaching inns and public houses for their passengers’ comfort. When short-stages appeared, they continued to wait at inns and taverns, in great part because of the availability of stabling for the horses and, to a lesser degree, for the convenience of the drivers and conductors; by the time buses arrived, it simply seemed to be the order of things that public transport stops were near hostelries.

35

While no one knew any longer how they had managed without this splendid system of transportation, they found plenty to complain about nonetheless. The bus conductor, in top hat and with a flower in his buttonhole, stood one-footed on a tiny step beside the door at the rear, raised about a third of the way up the bus so that he could see whether seats were vacant on top, and could tell new passengers which side to climb up. He also leant over, when crinolines were in fashion, to hold down the women’s hoops as they squeezed through the narrow doorway. Otherwise he swayed in place, holding on to a leather strap hanging by his shoulder and taking fares from departing passengers, his eyes always darting to find the next, as passengers hailed the buses anywhere along their routes.

Initially, there were no tickets and thus no check on the takings, apart from the word of the cad and the driver; they both therefore had a great incentive to stop for as many passengers as possible while admitting to the bare minimum at the end of the day. Wits claimed that perfectly innocent pedestrians were virtually kidnapped by the cads: they could, said a character in

Sketches by Boz

, ‘chuck an old gen’lm’n into the buss, shut him in, and rattle off, afore he knows where it’s a-going to’. For the same reason, no cads ever admitted to being full up: ‘Plenty o’ room, sir,’ they cried jovially, shouting ‘All right,’ and thumping on the roof to signal the driver to move off so the passenger couldn’t jump down when he saw that he would more or less have to sit on someone’s lap. Or, as Sophia Beale, a doctor’s young daughter from Kensington, wrote in 1850, ‘he...shouts

“Kilburne, Kilburne, come along mam, sixpence all the way” then he stops and runs back and pulls the lady along and stuffs her in and slams the door and begins to shout again “Kilburne, sixpence all the way”.’ That is, he did so until it rained, and then he charged passengers extra, from which he creamed off the surplus. A snowfall made matters even worse: an extra horse was needed for each bus, and that, together with the increased feed and hay prices in bad weather, sent fares up to 9d.

The drivers also competed for fares. An ‘old gentleman elevates his cane in the air, and runs with all his might towards our omnibus; we watch his progress with great interest’, Dickens had a passenger report in

Sketches by Boz

; ‘the door is opened to receive him, he suddenly disappears – he has been spirited away by the opposition.’ This was comedy, but court records indicate that many drivers raced along the streets to get ahead of the other buses and increase their chance of finding passengers: reckless driving was a regular charge. In 1844, two drivers were sentenced to a month’s hard labour

after a policeman testified to seeing them galloping down Regent Street; when they reached Pall Mall, one forced the other on to the pavement, where, nothing daunted, he continued at speed ‘for some time’. However, once a system of tickets was instituted, the complaints were the reverse: that the drivers dawdled along, while the cads became wilfully blind, ‘indifferent to shouts, threats, and entreaties of those who hail them from the road’, since they made no profit from the increased work.

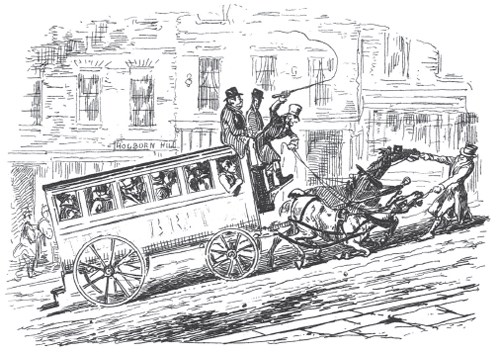

Even when drivers behaved responsibly, the streets of London, the weather and technology all made driving perilous. Holborn Hill, with its steep gradient across the Fleet Valley, was a well-known black spot for horses: extra horses were stabled at the bottom of the hill, to be harnessed on to each bus before it attempted the ascent. The bus companies also had men stationed at the top of the hill to thrust skids under the wheels of the buses as they started back down, slowing the motion of the wheels, both as a brake and to prevent the vehicle crashing against the horses’ heels. (As it was, bus drivers were strapped to a post behind their seat, which allowed them to throw their full weight on to the drag as they went downhill.) At the bottom of Holborn Hill more men were posted to dart into the road to remove the skids as the buses passed. And everywhere the rain and the mud routinely caused problems, making ‘horses sink slowly on their sides or knees, amid the greasy mud, and, having sunk, make fruitless endeavours to rise’. Accidents to the vehicles were so common that people wrote casually of an entire bus tipping over, as a matter of course. When there was a hard frost, no horse-drawn vehicles could go out at all (although small boys rejoiced, as they skated along the suddenly emptied roads).