Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (39 page)

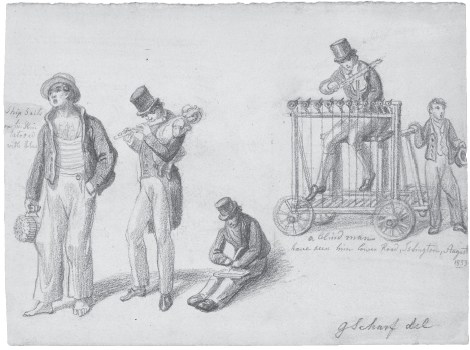

Ranking lower on the scale of attraction and approbation were the horse-and-cart organists, whose vast machines needed a cart drawn by two horses, crammed with ‘every known mechanical contrivance for the production of ear-stunning noises’. The most numerous of all organs on the street were the ordinary piano grinders, which at least had the benefit of not being too loud. Many of their practitioners were Italians living in Leather Lane: they carried the instrument on their backs, holding a staff as they walked that later doubled as a support to the instrument when they played. Flageolet organists and pianists were ‘the

élite

of the profession’, usually to be found in the West End ‘and on summer evenings…in the neighbourhood of some of

the Inns of Court’. Hurdy-gurdy players came in two classes: ‘little hopping, skipping, jumping, reeling, Savoyard or Swiss urchins, who dance and sing and grind and play…and men with sallow complexions, large dark eyes, and silver earrings, who stand erect and tranquil’. These men also played at ‘extempore “hop[s]” at the door of a suburban public house on a summer night’, or at some other form of working-class entertainment. Most bands settled around pubs and other entertainment venues, and were known to the locals: Dickens wrote that ‘Stabbers’s Band’ performed every Monday morning outside a Camden pub. Women players existed but were few and far between. Arthur Munby saw a female cornet player in Westminster, but that was extremely unusual.

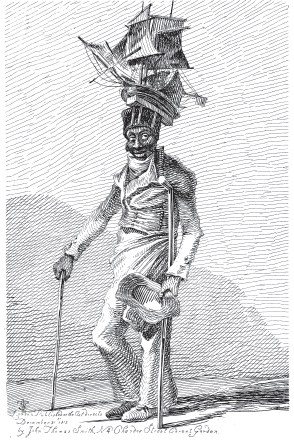

There were also singers, as individuals or in groups. Many singers performed because they had no skills, no tools of a trade, no choices. In the 1830s, Dickens saw near the Old Vic theatre a woman carrying a baby, ‘round whose meagre form the remnant of her own scanty shawl is carefully wrapped’, who warbled a popular ballad ‘in the hope of wringing a few pence from the compassionate passer-by’ – but failing. Munby watched the dancing and singing of five ‘Ethiopian Serenaders’ in Scotland Yard one day, the women with their ‘hair decked with network and rolls of scarlet cloth: they wore pink calico jackets, petticoats of spangled blue, ending a little below the knee: and red stockings and red boots’. When he spoke to them, he realized they were English, blacked-up. They may have been inspired by Joseph Johnson, a black sailor in the early part of the century, who had been wounded during the French wars. He built a model of the

Nelson

, which he wore on his head and, by dipping and swaying, made it ‘sail’ as he sang. He was well known, walking as far afield as Staines, Romford and St Albans on his rounds. In the 1840s, another singer wore a similar ship on his head while carrying a baby on his back: one observer noted that he had seen him perform thus over a full decade, ‘

the Child being always the same

’. Other wounded sailors, usually dressed in a uniform, sang sea shanties and theatre songs of heroic tars. (Alfred Bennett added that as far as he could remember he had never seen a soldier in such circumstances.)

Most householders professed to be driven mad by the constant jumble of music cranked out on the streets. It is unsurprising therefore to find the

magistrates courts filled with cases where residents attempted to have the musicians banned, with the musicians in turn applying to the courts for loss of earnings. An early cartoon by Robert Seymour, the original illustrator of

The Pickwick Papers

, showed a street musician refusing to be moved on for less than 6d: ‘d’ye think I does n’t know the walley o’peace and quietness?’ The cartoonist John Leech, before his death, commented, ‘Rather…than continue to be tormented in this way, I would prefer to go to the grave where there is no noise.’ And even Dickens, otherwise so passionately absorbed in street theatre, dismissed these ‘brazen performers on brazen instruments’.

There were, however, some who enjoyed the music. Since children adored performers of all sorts, many of the shows were geared towards them. Punch and Judy shows were generally elaborate street performances, requiring at

least two men: one to work the puppets, one to play the drum and mouth-organ beforehand, and to collect the money during the action. In the 1840s, Mayhew spoke to one man whose first Punch and Judy show had consisted of ‘twelve figures…Punch, Judy, Child, Beadle, Scaramouch, Nobody, Jack Ketch, the Grand Senoor, the Doctor, the Devil (there was no Ghost used then), Merry Andrew and the Blind Man…The heads…was all carved in wood…A set of new figures, dressed and all, would come to about fifteen pounds…A good show at the present time will cost three pounds odd for the stand alone…including the baize, the frontispiece, the back scene, the cottage, and the letter cloth.’ Given this outlay, Punch and Judy shows stuck to the more prosperous areas. Dickens wrote that in Camden in his childhood, ‘they knew better to do anything but squeak and drum…unless a collection was made in advance – which never succeeded’. Many did what they called ‘dwelling on horders’ (orders): performing outside a family’s house by request, with the children watching from a window. If there were no orders they performed a ‘long-pitch’, or thirty-minute show, at a busy junction. Because it was a rich man’s toy, in the summer ‘Punch mostly goes down to the seaside with the quality.’

There were other kinds of puppet shows as well, including fantoccini, which were marionettes similar in size to Punch and Judy, wheeled about on a cart. Various types of dancing puppets also appeared, such as sailors doing a hornpipe, or a skeleton that came apart as it danced, until only the skull was left, ‘footing it…merrily’. Most popular, with adults as well as children, were raree-, or peep-shows. The father of George Sanger (later ‘Lord’ George Sanger, the self-ennobled owner of one of the largest circuses in Europe) was an itinerant showman with a small peep-show: ‘a large box carried on the back, containing some movable and very gaudy pictures, and having six peep-holes fitted with fairly strong lenses. When a pitch was made the box was placed on a folding trestle and the public were invited to walk up’ and look at the various scenes depicted within. ‘My father…could “patter” in the most approved style, especially about the battle of Trafalgar [he had served on the

Victory

with Nelson]…In his white smock-frock, beaver hat, knee-breeches, with worsted stockings and low-buckled shoes’, he travelled the fairs in season and worked as a costermonger in the winter. By 1833,

he had bought a much larger box, with twenty-six holes in the side, for twenty-six simultaneous viewers, ‘the pictures being pulled up and down by strings’; at night they were lit by candles inside the box. The most popular scenes for these raree-shows were battles, famous (or local) murders, the death of William IV, Napoleon’s return from Elba, or at Waterloo, the death of Nelson and ‘The Queen embarking to start for Scotland, from the Dockyard at Voolich’, as well as famous scenes from popular melodramas and Christmas pantomimes.

Animal shows were also in demand. In the 1820s, there had been a famous dancing-bear and monkey team: the monkey, dressed as a soldier, danced on the bear’s head, and the bear tumbled and danced. But this was unusual, and generally the animals used were more domestic. In the mid-1830s, George Sanger himself began to work, aged about eleven, buying canaries, redpoles and white mice, which he taught to do tricks: the birds drew and fired a cannon, rode in a miniature coach, walked a tightrope and danced; the mice climbed poles, fetched flags ‘and other tiny tricks’. A few carts housed ‘Happy Families’, a number of unlikely animals living happily together in one cage: dogs, cats, monkeys, various types of bird, rats, guinea pigs and so on, which performed tricks. One Happy Family exhibitor even claimed to have been invited to show his ‘Family’ to Queen Victoria.

Some shows needed less money to set up. Street conjurors and acrobats travelled in pairs, dressed in overcoats, one carrying a drum, the other a ladder. If a crowd gathered, they put down the drum and rolled out a mat; then the conjuror brought out ‘cards, cups and balls’. Their coats came off to display a red-and-white motley for the clown and ‘a loose pair of white tights, garnished with strips of red and green tape’ for the conjuror. They did a comic cross-talk act – Conjuror: ‘Beat the drum.’ Clown: ‘Beat the donkey?’ – after which the conjuror juggled, balanced balls, swords and sticks, and did card tricks, all the while keeping up his comic dialogue with the clown, who meanwhile had the important role of taking up the collection in the crowd. After ten or fifteen minutes, they picked up their mat, put on their coats and headed for a new pitch. Sometimes the group was larger, comprising a strong man, a juggler, ‘a snake, sword, and knife-swallower’ or a contortionist; sometimes the clown was dressed as a soldier,

and his comic business consisted of riddles, jokes, songs and, ‘where the halfpence are very plentiful’, a funny dance.

As with the singers, many performers were street entertainers because they had no other way of earning a living. A showman’s child in the 1830s did a ‘Cackler Dance’, skipping blindfolded between twenty eggs. Sala remembered a man who stood outside St Martin’s-le-Grand with a piece of paper, shaping and reshaping it, calling out, ‘It forms…now it forms a jockey-cap, now a church-door, a fan, a mat, the paddle-boxes of a steamer’, hoping for a few coins. Profile cutters created paper silhouettes. Pavement chalkers were obviously beyond all possibility of work: one who had a pitch in the New Kent Road had been an usher (a junior teacher) until he had a stroke. Children danced, sang or turned cartwheels. Many congregated by the riverside pubs, hoping that sporting gentlemen sitting on balconies would throw pennies into the river for the amusement of watching the children dive for them. In the 1850s, children also stood under the viaduct at Bermondsey, where the Greenwich excursion train stopped for ticket inspection, shouting, ‘Throw down your mouldy coppers!’ Cheery and slightly drunk, the day-trippers obeyed.

The leisure industry and the street world intersected here informally, but more often the two worlds met in more planned ways.

10.

LEISURE FOR ALL

A morning walk in the park: what could be more ordinary? But London, today considered to be one of the world’s cities most generously provisioned with public parks, did not historically have this largesse available to all. Its nineteenth-century development can be seen, in some ways, as a narrative of how green spaces were gradually made accessible to the masses. As late as 1855, in Trollope’s

The Warden

, the Revd Mr Harding spends a day in London being constantly harried from place to place: there were few locations where one might sit without paying for the privilege by buying something to drink or eat. Gentlemen might walk in the park, but sitting on a bench was not respectable. Both St James’s Park and Green Park were officially private Crown land, where access could be arbitrarily withdrawn.

81

In reality, even though their gates were locked nightly at ten, by the seventeenth century there were over 6,500 keys to the gates of St James’s alone, and the walls were easily scaled, too. When George II lived at Kensington Palace in the eighteenth century, Kensington Gardens was open to the public only at weekends. After the court moved elsewhere, the public hours were increased, but regulations, enforced by park-keepers, were designed to keep the masses out.

Similarly, London’s unique green spaces – its squares, so prominent a part of the city today – were either not open to the public or were not planned to

be green. In the seventeenth century Inigo Jones designed the first London square, Covent Garden Piazza, in the Italianate style: as a paved space. After the Restoration, more paved squares were built, such as Lincoln’s Inn and Leicester Fields (where, in 1760, George II, as he was soon to be, lived in Savile House; he was proclaimed king in the square itself ). But throughout the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries the paving gave way to grass as a vogue for planted squares spread: first in Soho Square, St James’s Square and Panton Square, all in Westminster; in Bridgewater Square, near the Barbican; and in Queen Square in Bloomsbury. By the start of the nineteenth century, there were about fifty squares in London; forty years later there were 200; by 1928 the figure had risen to 461.