The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (57 page)

Read The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London Online

Authors: Judith Flanders

Tags: #History, #General, #Social History

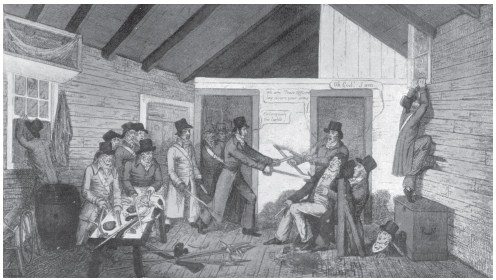

At one o’clock the procession reached the Haymarket, where the men were placed in the pillory as the howling mob circled and bayed, continuing to pelt the prisoners with ordure. After an hour four of the men were removed to Coldbath Fields prison; the other two had been sentenced to an additional hour because of previous convictions. They were both barely conscious when they came to be released. This was not unusual, and they might even be said to have been fortunate. Some of those pilloried were blinded by flying stones, while in 1815 a man died in the pillory, causing MPs to call for its abolition. (However, this was not because of, or not entirely because of, the fatality. What shocked them was the uncertainty of the punishment: when a publisher was sent to the pillory for publishing Thomas Paine’s banned work,

The Age of Reason

, the crowd cheered him wildly, offering him food and drink.)

Although the pillory wasn’t immediately abolished, after 1816 the punishment was confined to perjurers, and the violence subsided, perhaps because this crime aroused fewer passions. The journalist Henry Vizetelly remembered seeing someone in the pillory in front of Newgate one evening when he was young. Although the crowd seemed to him as big as for any execution, the people were for the most part ‘more curious than vindictive’, and

they obeyed the ban on ‘missiles being thrown’. The last man to be pilloried in Britain was a fishmonger who fell into debt and perjured himself during his trial. When he stood in the pillory in June 1830,

The Times

noted that it had been twelve years since the pillory had last been used.

The pillory was a temporary wooden erection in the street. Far more formidable was the seemingly eternal great stone wall of Newgate, next to the Old Bailey, the Central Court of Criminal Justice. Given the looming presence of the prisons in the city, it is perhaps not surprising that many of the prisons had nicknames that were recognized by much of the population, for they were part of everyone’s daily life. Pentonville, built along new lines, to reform rather than punish, was ridiculed as ‘the Model’; Millbank was the Tench, from ‘Penitentiary’; Horsemonger Lane gaol was either the Lane or, more poetically, the Old Horse; Tothill Fields was, for some inscrutable reason, the Tea Garden; Clerkenwell was the Wells; and Coldbath Fields was the Steel, short for ‘Bastille’. Newgate was known, from the eighteenth century, as the Stone Jug. And stone was the predominating element, its façade unpierced by any windows, with one ‘small, black, iron-studded door...low and narrow as the entrance to a vaulted grave’. It was, said one twentieth-century architectural historian, ‘an extraordinary building...a great Palace of Retribution’.

This was the place where the ultimate public state-sanctioned violence occurred: execution. Prisons and death were firmly linked. In the 1840s, one journalist wrote that the current slang word for ‘prison’ was ‘sturbon’, from ‘

gestorben

’, German for dead, hence a place of execution. (A more likely derivation is from the Romany ‘

stariben

’; whichever the origin, ‘sturbon’ is the source of the word ‘stir’ for prison.) From 1784, London executions were held either outside Newgate, in the City of London, or in front of Horsemonger Lane gaol in Southwark (Horsemonger Lane is now Harper Road): in both cases, in the middle of densely populated neighbourhoods. Among connoisseurs of executions, it was considered that the crowds at Horsemonger Lane had the better view, as the prison had a specially built gallows on the roof. The scaffold at Newgate was not as easily viewed from the small clearing in front of the gaol, but viewers felt closer to events.

Newgate was just yards from Smithfield and not much further from St Paul’s. ‘There, at the very core of London, in the heart of its business and animation...upon the very spot on which the vendors of soup and fish and damaged fruit are now plying their trades – scores of human beings...have been hurried violently and swiftly from the world.’ This was Dickens writing in the late 1830s, although he never became more used to either the idea or the actuality of public executions. In 1840, he attended an execution for the first time, when a valet, Benjamin-François Courvoisier, was hanged for the murder of his master. Dickens, who watched, sickened, among the crowd, thought he had spent ‘a ghastly night in Hades with the demons’.

Dickens, like many middle-class commentators, often wrote of the crowds who witnessed the executions as though they were all criminals and vagrants, but that does not appear to have been the case. Nearly half a century earlier, in 1807, thirty people were killed in a crush at one execution, and the inquest listed their occupations. They included ‘a respectable

gentleman’ (that is, a middle-class man of means), an apprentice piano manufacturer, a wine merchant’s son and a shoemaker’s child. Among the wounded were a tavern keeper, a pieman, a porter, a weaver, a brush maker, a carpenter’s apprentice and a butcher’s child – a good cross-section of the London streets. In the 1840s, Thackeray also attended an execution, writing later that the bystanders came from ‘all ranks and degrees – mechanics, gentlemen, pickpockets, members of both Houses of Parliament, streetwalkers, newspaper-writers...dandies, with mustachios and cigars...family parties of simple honest tradesmen and their wives’.

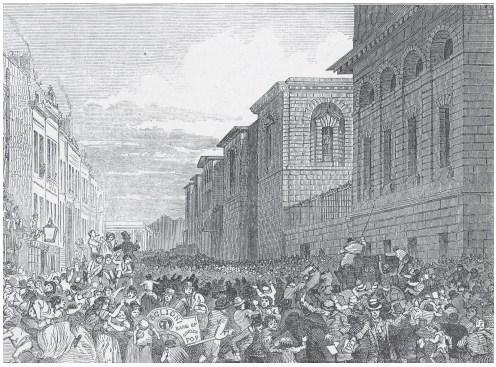

Until 1836, the condemned were executed forty-eight hours after their conviction, unless a Sunday intervened, in which case the hanging was seventy-two hours later. After this date, more time was allowed for legal arguments to be heard if there was a liklihood of clemency, or there were petitions for mercy, or, later, if appeals were planned. Executions were traditionally held outside Newgate or Horsemonger Lane gaol on Monday mornings at eight. For crimes that had captured the public imagination, preparation might begin days before the execution. For the double execution of Maria and Frederick Manning in November 1849, convicted of the murder of her lover, landlords near Horsemonger Lane gaol erected scaffolding on their buildings overlooking the gallows to create additional seating. The police cleared the area in front of the gaol three full days before the hanging, putting up barricades and blocking off streets to prevent a repeat of those deaths by overcrowding.

The gallows was traditionally erected during the night before the execution, and crowds milled around, shouting encouragement or derision, depending on the attitude towards the convicted, while street sellers and pubs supplied their wants. In 1836, before the execution of James Greenacre, convicted of killing and dismembering his washerwoman fiancée, and scattering her in sections across London, the appearance of the scaffold ‘was hailed with three cheers of deafening applause’. This was repeated when the great transverse beam was raised and yet again when the noose was put up. Throughout the night before each Newgate execution, the bell of St Sepulchre tolled for the dead man before he had died. Fagin listens to it from the condemned cell with ‘despair. The boom of every iron bell came laden

with the one deep hollow sound – Death.’

148

By six o’clock on an execution morning, the open space in front of the prison was thronged with bystanders, as were the surrounding streets, every window and every rooftop having been hired out long before. For the execution of the Mannings, Dickens and his friends paid ten guineas (‘extremely moderate’, in Dickens’ view) for a rooftop vantage point.

After the French Revolution, the number of crimes punishable by death, and the consequent number of executions, had risen sharply. Prompted by fear of the mob, of the returning, now unemployed, soldiers, and of the unruly working classes, the number of people hanged in the thirty years between 1800 and 1830 was double the figure for those executed in the previous half-century. In 1837, the year of

Oliver Twist

, as well as the year Victoria came to the throne, 438 death sentences were passed in Britain. And in that novel, just as in that year, it seemed to be a subliminal idea in the minds of many of the middle-class upholders of the Poor Law that hanging was the natural fate of the poor. When Oliver asks for ‘more’, the Poor Law Guardian says, ‘That boy will be hung...I know that boy will be hung’; and when Oliver is apprenticed, his master ‘felt a strange presentiment from the very first, that that audacious young savage would come to be hung!’

However, 1837 was the peak, and a greatly exaggerated peak. Two years later the number of death sentences passed in Britain had declined by nearly 90 per cent, to just fifty-six. This was not because of establishment repugnance for the death penalty, but rather because those at risk of being victims

of property crime – the rich and the business classes – realized that juries were refusing to convict because of the harshness of the penalties. The number of crimes punishable by death was reduced, with transportation or penal servitude being imposed instead, in order to increase the number of guilty verdicts. From that time, the number of executions steadily decreased. Attending them, however, reached the height of its popularity from the late 1840s to the early 1860s: scarcity drove demand. As the century progressed, this was compounded by the railways, which enabled more people, from a wider area, to travel to see the fun; and by the spread of cheap newspapers, attracting more readers by drumming up interest in each crime. When the crowds were mixed and the events popular, their festival air disturbed many. A snippet of dialogue from Punch and Judy captures well the grisly good temper of many execution assemblies with its cheerful disregard for authority:

LORD CHIEF JUSTICE: Hollo! Punch, my boy!

PUNCH: Hollo! Who are you with your head like a cauliflower?...

LORD CHIEF JUSTICE: You’re a murderer, and you must come and be hanged.

PUNCH: I’ll be hanged if I do. [

Knocks down the Chief Justice and dances and sings.

]

Allowing for the exaggeration of a puppet show, it was demonstrably the case that this tone sometimes mirrored reality. In 1820, ten men were charged with conspiracy to assassinate the prime minister and his entire cabinet. It was said that the Cato Street conspirators, named for the street in Marylebone where they had met, had hoped to establish a ‘Committee of Public Safety’ modelled on the bloody French Revolutionary group that had sent so many to the guillotine less than three decades earlier. Ten men were found guilty and sentenced to be hanged, drawn (that is, eviscerated while still partially alive) and quartered (cut in four), as the statute book demanded for high treason. Five had their sentences commuted to transportation for life, but the other five were executed, their sentences being moderated to hanging and the beheading of their corpses. This was carried out, on 1 May of that same year, in front of Newgate. Twenty years later Thackeray claimed that when the heads were held up to the huge gathering to show the fate that awaited all traitors, the executioner, his hands slippery with gore, fumbled the final head, at which a comedian in the crowd yelled, ‘Butter-fingers!’ – to the vast amusement of all. Indeed, the execution was a subject for jokes even before the event. When the fashionable fencing master Henry Angelo was in search of a window overlooking the scaffold, one landlord demanded a fee of one guinea. Angelo exclaimed: ‘What! to see four men have their heads cut off? I’ll give you half a crown a head.’

149

More than anything else, it was jokes of this type that troubled many. Dickens was not against the death penalty, merely against the public levity that accompanied its enactment. After Courvoisier’s execution, he wrote in the

Daily News

, ‘From the moment of my arrival...down to the time when I saw the body with its dangling head, being carried on a wooden bier

into the gaol – I did not see one token in all the immense crowd...of any one emotion suitable to the occasion...nothing but ribaldry, debauchery, levity, drunkenness, and flaunting vice.’ This was not always the case: a great deal depended on who was being executed, and why. When the servant Eliza Fenning was hanged for attempted murder in 1815, the miscarriage of justice was so blatant that the working-class spectators, perhaps as many as 50,000 strong, stood, it was reported, in total silence as the victim in white appeared on the scaffold. But when the ex-lady’s maid, Maria Manning, and her husband were executed at in 1849, greeted her with a raucous rendition of ‘Oh Mrs Manning, don’t you cry for me’, sung to the tune of ‘Oh Susannah’.