The Victorian Internet (11 page)

Read The Victorian Internet Online

Authors: Tom Standage

This ambiguous message was taken by the French chief of staff, an anti-Dreyfusard who was anxious to secure a conviction,

as proof that Dreyfus was guilty. So when, a few days later, the codebreakers decided that the last portion of the message

actually meant "to avoid press comment," their superiors were not pleased. There was only one way to see which interpretation

was correct: to get Panizzardi to send another message, whose exact wording was known, in the same code. A double agent duly

passed a bogus morsel of information to Panizzardi, and when he passed it on in coded form to his superiors in Rome, a copy

was passed back to the Bureau du Chiffre. When they decoded it, it confirmed their second interpretation; Dreyfus was innocent.

However, by this time the army was unwilling to admit that it had got the wrong man, so an exaggerated version of the original

flawed decoding was presented at Dreyfus's trial. (The complexity of the code meant that the telegram could be claimed to

have said almost anything.) Consequently, Dreyfus was found guilty and sent to prison on Devil's Island, a colony off the

coast of French Guiana.

Perhaps appropriately for someone wrongly convicted by a telegram, Dreyfus was eventually freed as a result of another telegram.

In 1896, the contents of a wastepaper basket from the office of the German military attache in Paris were examined by French

intelligence staff and found to include a torn-up pneumatic telegram form that had never been sent. When pieced together,

it was found that the form contained a message to another officer at the French War Ministry, Major Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy,

implicating him in the offenses attributed to Dreyfus. It was, however, another ten years before Dreyfus was finally reinstated.

By this time, his case had become a cause cele-bre among Paris intellectuals led by the novelist Emile Zola, who wrote his

famous article "J'Accuse" in Dreyfus's defense. (The case remained such a political hot potato that it was only in 1995 that

the French army finally conceded that Dreyfus had been innocent all along.)

So much for universal peace and understanding. The telegraph was providing new ways to cheat, steal, lie, and deceive.

All the ends of the earth will be wooed into the electric telegraph circuit.

—SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN,

185?

S

PIES AND CRIMINALS are invariably among the first to take advantage of new modes of communication. But lovers are never far

behind.

There are no known examples of amorous messages being passed over the optical telegraph, since it was not available for general

public use; but within a few months of the electric telegraph being opened to the public, it was being used for something

that even the most farsighted of telegraph advocates had never dared to imagine: to conduct an on-line wedding.

The bride was in Boston, and the groom in New York; the exact date is unknown, but the story of the wedding was common currency

by the time a small book,

Anecdotes

of the Telegraph,

was published in London in 1848. It was described as "a story which throws into the shade all the feats that have been performed

by our British telegraph."

The daughter of a wealthy Boston merchant had fallen in love with Mr. B., a clerk in her father's countinghouse. Although

her father had promised her hand to someone else, she decided to disregard his intentions and marry Mr. B. instead. When her

father found out, he put the young man on a ship and sent him away on business to England.

The ship made a stopover in New York, where the young woman sent her intended a message, asking him to present himself at

the telegraph office with a magistrate at an agreed-upon time. At the appointed hour she was at the other end of the wire

in the Boston telegraph office, and, with the telegraph operators relaying their words to and fro in Morse code, the two were

duly wed by the magistrate. "The exchange of consent being given by the electric flash, they were thus married by telegraph,"

reports a contemporary account.

Surprisingly, the marriage was deemed to be legally binding. The woman's father tried to insist that his daughter marry the

man he had chosen for her, but she said she was already married to Mr. B., who was by then on his way to England. The merchant

apparently "threatened to protest against the validity of the marriage, but did not carry his threat into execution."

In Britain, meanwhile, there was concern that the telegraph could impede the course of true love. Plans had been put forward

to extend the telegraph network along the Caledonian railway to Gretna Green, a village just north of the Scottish border

that was renowned as a wedding destination for runaway couples from south of the border, since "marriages of declaration"

without a minister or magistrate were legal in Scotland but not in England. The extension of the telegraph would mean that

runaway couples traveling by train could no longer outrun the news of their elopement, and a disapproving parent could alert

the authorities at Gretna Green before they had even arrived. "What an enemy science is to romance and love!" declared one

critic.

Clearly, the new technologies would take some getting used to and offered both advantages and drawbacks to amorous correspondents.

In general, though, the high cost and lack of secrecy meant that for the general public, the telegram did not represent much

of a threat to traditional letter writing. However, the impact of the telegraph on the love lives of its operators—who spent

their working lives communicating with each other over the wires—was far more profound.

T

ELEGRAPH operators were members of a closed, exclusive community. They had their own customs and vocabulary, and a strict

pecking order, based on the speed at which they could send and receive messages. The finest operators worked in the central

telegraph offices of major cities; rural outposts, which handled only a few messages a day, were usually operated on a part-time

basis by less experienced operators. But collectively, the world's telegraphers represented an online community encompassing

thousands of people, very few of whom ever met face-to-face. And despite the apparently impersonal nature of communicating

by wire, it was in fact an extremely subtle and intimate means of communication.

Experienced operators could even recognize their friends merely from the style of their Morse code-something that was, apparently,

as recognizable as an individual human voice. Each operator on a particular telegraph line also had a two-letter signature,

or "sig," with which to identify themselves on-line-, a Detroit operator named Mills, for example, used the signature MS,

while Miss A. Edwards, another operator, was known as AE.

Operators often developed partnerships with other operators in distant offices. Thomas Edison described such a pairing, established

in the 1860s: "When on the New York No. 1 wire that I worked in Boston, there was an operator named Jerry Borst at the other

end. He was a first-class receiver and a rapid sender. We made up a scheme to hold this wire, so he changed one letter of

the alphabet and I soon got used to it; and finally we changed three letters. If any operator tried to receive from Borst,

he couldn't do it, so Borst and I always worked together."

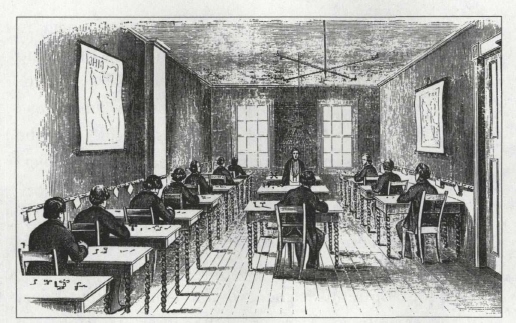

Atypical midsize U.S. telegraph office. Operators were seated at wooden tables, each equipped with a Morse key and sounder.

Operators often claimed ownership over particular wires in this way; although unofficial, the practice did in fact make for

smoother, less error-prone transmission, since the sender and receiver knew each other's capabilities. Even so, since it often

resulted in operators sitting by relatively quiet wires in order to stay in contact with their friends while other wires were

overloaded, companies tried to prevent it from happening by moving operators around (something that the operators referred

to as being "snatched"). One notice, posted in a telegraph office in 1898, read as follows: "Those operators who object to

being 'snatched,' as they term it, are reminded that upon entering the employ of this company they were not engaged to work

any particular wire or wires, to sit at dead or comparatively idle ones when their services could be utilized elsewhere, and

the sooner they realize this the better it will be for all concerned."

During quiet periods, however, the on-line interaction really got going, with stories, jokes, and local gossip circulated

over the wires. According to one account, "stories are told, opinions exchanged, and laughs enjoyed, just as if the participants

were sitting together at a club." In some cases the tales passing over the wires would find their way into the local newspapers.

Most did not because, according to Edison, they were far too smutty or anatomically explicit.

Bored and lonely operators would also play checkers over the wires, using a numbering system to identify the squares of the

board that dated back to the chess games played over the Washington-Baltimore line in the 1840s. Some telegraphers in remote

outposts even preferred online contact with other telegraphers to socializing with the locals. Thomas Stevens, a British telegraph

operator stationed in Persia, shunned the local community in favor of telegraphic interaction with other Britons. "How companionable

it was, that bit of civilization in a barbarous country," he wrote of his telegraphic friends, some of whom were thousands

of miles away. (So much for the telegraph's ability to forge links between people of different nations.)

On one occasion the employees of the American Telegraph Company lines between Boston and Calais, Maine, held a meeting by

telegraph after hours. The meeting was attended by hundreds of operators in thirty-three offices along the 700-mile line.

Each speaker tapped out his words in Morse code so that "all the offices upon the line received his remarks at the same moment,

thus annihilating space and time, and bringing together the different parties, in effect, as near to each other as though

they were in the same room, although actually separated by hundreds of miles," according to one account. After passing various

resolutions, the employees adjourned the meeting "in great harmony and kindly feeling" after about an hour. (In Britain,

Punch

magazine then suggested that holding parliamentary proceedings by telegraph might restrain some of the more verbose speakers

in the house from going on for too long.)

T

HE TELEGRAPHIC community included a large number of women. By the 1870s, the ratio of men to women at the Western Union main

office in New York was two to one; in fact, women telegraphers dated back to 1846, when one Sarah G. Bagley was appointed

as an operator in Lowell, Massachusetts, after the opening of the New York-Boston line.

In Britain, female telegraphers were usually the daughters of clergymen, tradesmen, and government clerks, and were typically

between eighteen and thirty years old and unmarried. Women were regarded as "admirable manipulators of instruments" well suited

to telegraphy (since it wasn't too strenuous), and they could spend the quiet periods reading or knitting. The hours were

long, though; most operators, including the women, worked ten hours a day, six days a week.

"Ordinarily an operator can tell a woman the moment he hears her working the wire," claimed the

Western Electrician

magazine in 1891. "He tells by her touch on the key. Women, as a rule, telegraphers say, do not touch the key of their instruments

as firmly as men do. Occasionally, however, there is one without this characteristic distinction in style." In most cases,

female operators were segregated from the men, and some companies employed a "matron" to keep an eye on them. But while the

female operators were physically isolated from their male counterparts, they were of course in direct contact with them over

the telegraph network throughout the working day. So it hardly needs saying that many working relationships flowered into

on-line romances. According to one writer, "Sometimes these flourished; sometimes they came to an abrupt halt when the operators

met for the first time."

"Romances of the Telegraph," an article published in

Western Electrician

in 1891, tells the story of a "pretty little romance" that took place at a remote station out in the desert at Yuma, Arizona,

near the border with Mexico. "A more uninviting place of abode could scarcely be found. The station consists merely of a big

water tank, a rough shed called the telegraph office, and another shed in which half a dozen trackmen live. During the summer

months life at the little desert station was almost unbearable." There was nothing to do, it was unbearably hot and very difficult

to sleep, so unsurprisingly the operator at the station, John Stansbury, turned to the telegraph wire for companionship.

An acquaintance soon sprung up between Stansbury and the operator in Banning, California, known as "Mat," whom Stansbury described

as a "jolly, cheerful sort of fellow." They soon became firm friends and agreed to spend their vacation together in the mountains

hunting and fishing. Every detail of the trip was arranged, with Mat insisting that they take rubber boots for fishing, even

though Stansbury said he was quite happy in his bare feet. But at the last minute Mat pulled out of the trip, having decided

to take the train to vacation in New Mexico instead, a trip that involved passing through Yuma, Stans-bury's station. But

by the time Mat arrived at Yuma, Stansbury had been taken ill with a fever and was quite delirious.

"During the days of my agony I was vaguely aware of gentle, womanly hands and a kindly female presence in my sick-room," Stansbury

later wrote. "And when I returned to the conscious world I was not surprised to find a fair and pleasant face beside me. Its

owner said that she had been on the train when I was found stricken down, and had stayed to minister to my sore need. The

idea may seem preposterous, but I believe the foundation for my affection had been laid while the unconsciousness of fever

was still upon me, and the affection grew into the deepest love as she cared for me during the days of my convalescence. After

a time I ventured to tell her of my love, and to ask her if she would be mine; but I was not prepared for her answer. 'John,'

she said, 'do you really mean that you wish to marry a girl that insists upon wearing rubber boots?'

'Mat!' I said, for I was completely beaten. Then it flashed upon me. She was the operator at Banning, and I, like a fool,

had always taken it for granted that she was a man. I am not going to tell you how I convinced her that I wanted to marry

her, boots, and all, but I did it, and here we are on our wedding journey. The Southern Pacific Telegraph Company has lost

an operator, but I calculate that I am ahead on the deal."

Minnie Swan Mitchell, a young operator in the 1880s, recalled that "many a telegraph romance begun 'over the wire' culminated

in marriage." Ella Cheever Thayer's 1879 novel

Wired Love

even built its plot around an on-line courtship.

Inevitably, some ill-starred on-line romances had repercussions in the real world. One such cautionary tale was described

in "The Dangers of Wired Love," an article published in

Electrical World

in 1886. It concerned George W. McCutcheon of Brooklyn, who ran a newsstand assisted by his twenty-year-old daughter, Maggie.

Business was booming, so he decided to install a telegraph line, with Maggie as its operator. But he soon discovered that

she was "keeping up a flirtation" with several young men over the wires, including Frank Frisbie, a married man who worked

in the telegraph office of the Long Island Railroad. Over the wires, Maggie invited Frisbie to visit her, and he accepted.

When her father found out, he forbade the visit. Maggie began seeing Frisbie on the sly. McCutcheon tried moving his newsstand,

but Maggie soon found work in a nearby telegraph office and resumed the relationship. Eventually, her father pursued her to

a rendezvous and threatened to "blow her brains out." She had him arrested, and he was charged with threatening behavior.