The Virgin Cure

ALSO BY

A

MI

M

C

K

AY

The Birth House

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright © 2011 Ami McKay

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Published in 2011 by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited. Distributed by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Knopf Canada and colophon are trademarks.

www.randomhouse.ca

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

McKay, Ami, 1968–

The virgin cure / Ami McKay.

eISBN: 978-0-307-37409-7

1. New York (N.Y.)–Fiction. I. Title.

PS8625.K387V57 2011 C813.′6 C2011-901423-5

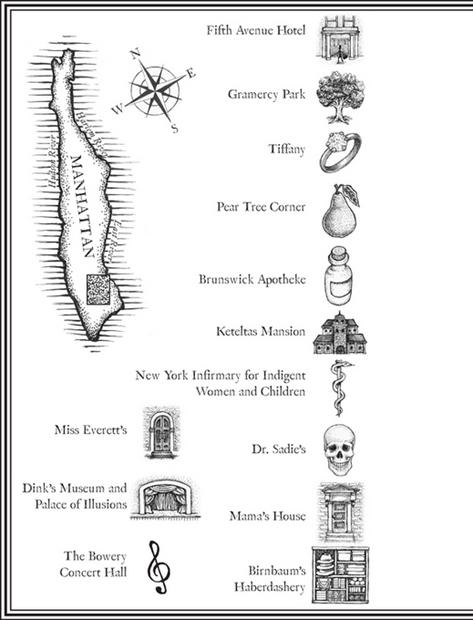

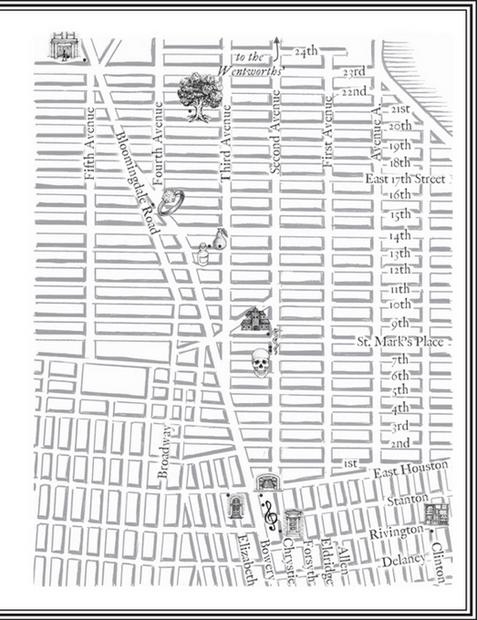

Map by Erin Cooper

Cover images: (moths, paper) Lisa Hubbard/botanica/getty images; (girl) Raisa Kanareva/

dreamstime.com

/

Cover design: Kelly Hill

v3.1

For Sarah Fonda Mackintosh—doctor, mother, rebel;

and for my mother, who never let me forget that

I came from such stuff.

Contents

Recall ages—One age is but a part—ages are but a part;

Recall the angers, bickerings, delusions, superstitions, of the idea of caste,

Recall the bloody cruelties and crimes.

Anticipate the best women;

I say an unnumbered new race of hardy and well-defined

women are to spread through all These States,

I say a girl fit for These States must be free, capable,

dauntless, just the same as a boy.

—WALT WHITMAN

Shrewdness, large capital, business enterprise, are all enlisted in the lawless stimulation of this mighty instinct of sex.

—DR. ELIZABETH BLACKWELL

,

founder of the New York Infirmary

for Indigent Women and Children

I

am Moth, a girl from the lowest part of Chrystie Street, born to a slum-house mystic and the man who broke her heart.

My father ran off when I was three years old. He emptied the rent money out of the biscuit tin and took my mother’s only piece of silver—a tarnished sugar bowl she’d found in the rubble of a Third Avenue fire.

“Don’t go …” Mama would call out in her sleep, begging and pulling at the blanket we shared as if it were the sleeve of my father’s coat. Lying next to her, I’d wish for morning and the hours when she’d go back to hating him. At least then her bitterness would be awake enough to keep her alive.

She never held my hand in hers or let me kiss her cheeks. If I asked to sit on her lap, she’d pout and push me away and say, “When you were a baby, I held you until I thought my arms would fall off. Oh, Child, that should be enough.”

I didn’t mind. I loved her.

I loved the way she’d tie her silk scarf around her head and then bring the ends of it to trail down her neck. I loved how she’d grin, baring her teeth all the way up to the top of her gums when she looked at herself in the mirror, how she’d toss her shawl around her shoulders and run her fingers through the black fringe of it before setting her fortuneteller’s sign in the window for the day. The sign had a pretty, long-fingered hand painted right in the middle, with lines and arrows and words criss-crossing the palm.

The Ring of Solomon, The Girdle of Venus. Head, heart, fate, fortune, life

. Those were the first words I ever read.

It was my father who gave me my name. Mama said it came to him at a place called Pear Tree Corner—“whispered by a tree so old it knew all the secrets of New York.” The apothecary who owned the storefront there told my father that he could ask the tree any question he liked and if he listened hard enough it would answer. My father believed him.

“Call the child

Moth,”

the twisted tree had said, its branches bending low, leaves brushing against my father’s ear. Mama had been there too, round-faced and waddling with me inside her belly, but she didn’t hear it.

“It was the strangest, most curious thing,” my father told her. “Like when a pretty girl first tells you she loves you. I swear to God.”

Mama said she’d rather call me Ada, after Miss Ada St. Clair, the wealthiest lady she’d ever met, but my father wouldn’t allow it. He didn’t care that Miss St. Clair had a diamond ring for every finger and two pug dogs grunting and panting at her feet. He was sure that going against what the tree had said would bring bad luck.