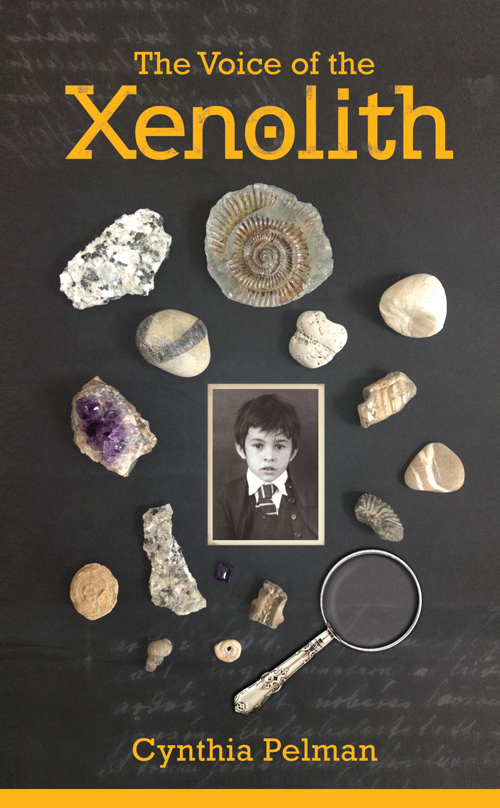

The Voice of the Xenolith

Read The Voice of the Xenolith Online

Authors: Cynthia Pelman

3 Amethysts and other minerals

12 The perfection of Moleskine notebooks

22 A story can happen when no-one is looking

28 The secret knowledge of things

Also by Cynthia Pelman

Joshy Finds his Voice

Voices from the Sand

This book is dedicated

to the memory of

Ignace Edelstein,

born 16th February 1903

and murdered in Auschwitz

14th July 1942.

This book is based on my many years of working with children who have difficulty in finding their voice. Some of them have had challenges in developing speech and language; others have had general developmental delays. Some children were suffering from the effects of growing up in conditions of violence and deprivation. These are just a few of the reasons why children might struggle to find a voice of their own.

The child who tells her story in this book has a condition called selective mutism: she is able to speak, but not outside her home, or at school, or with anyone other than her own family. With the help of a speech therapist she learns to overcome her difficulties. This child and her family are fictitious; they are not based on any particular person or family, but are, in part, composite characters.

For more information on selective mutism please see the bibliography at the back of this book.

The other character in the book, Ignace Edelstein, was a real person, a victim of the Holocaust. I was allocated his name by the âGuardian of the Memory' project, in order to honour his memory. I have tried to find as much information as I could about him and about his life; much of what I have written is speculative, but it is based on real facts.

![]()

A

xenolith

(Ancient Greek: “foreign rock”) is a rock fragment which becomes enveloped in a larger rock. It is sometimes called an inclusion. It differs in origin and structure from the rock which encloses it. These rock fragments form at high temperatures and pressures, deep down in the mantle of the earth.

To be considered a true xenolith, the included rock must be identifiably different from the rock in which it is enveloped.

“And the too much of my speaking:

heaped up round the little

crystal dressed in the style of your silence.”

From âBelow' by Paul Celan (1920-1970)

Stones

When I was five I started school, and I didn’t speak for a whole year.

That is actually not totally accurate, and it is better to say things accurately if you say them at all. What happened was, I did speak at home, to my family, but I didn’t speak to anyone outside the family. I didn’t speak at school or anywhere outside the house.

Some people at school tried to get me to talk. Some of the teachers tried to be friendly, others got cross because I didn’t talk, and some of them just gave up and walked away. And some didn’t mind; it didn’t bother them and they didn’t bother me.

Actually, the first teacher I had, in Year One, was okay. She did her best not to let other people make me feel pressured. “Leave her alone, she’s just a bit shy, she’ll be fine!” she said.

Maybe I was shy, and maybe I wasn’t. Maybe I am still shy, I don’t know. But I didn’t speak at school for the whole of my first year there.

Now I am thirteen and I do speak. But not to everybody, and not a lot. I still prefer to talk when I have something important to say. I don’t like small talk, and I don’t chat.

![]()

I do talk when I have to ask someone something, to get information. Getting information is what I do a lot of, because my interest is in finding things. Things that are buried, or lost. I look for buried treasure, for things that have to be dug up and uncovered. Or recovered. That is the career I have chosen for when I finish school: I am going to be a palaeontologist. Or a detective.

![]()

People in my family sometimes call me Am for short but my actual name is Amethyst. I don’t mind being called Am, because it is who I ‘am’. But I prefer to be called Amethyst by people who are not in my family.

At school someone once called me Amy for short. That was not okay. Amy is not my name; Amy is another name altogether. So even though I don’t usually talk much, I did talk then. I told her my name is Amethyst, not Amy.

Since then nobody has called me Amy.

My father gave me the name Amethyst, because he is a geologist, and he chose names of stones or minerals for his children. My brother is Jasper. He is nearly nine years old. I am four and a half years older than him. My parents hoped they would have another child and they were going to call her Ruby, but that didn’t happen.

I think my parents should have stone names too, like us. My mom’s name is Carys but my dad sometimes calls my mom Crystal. It suits her. My dad told us it makes him think of crystal clear water when you are hot and sweaty in the desert. He spends a lot of time working in deserts so he should know.

We couldn’t decide which name my dad should choose for himself; his name is Mike and that is not a stone name. But it is too complicated to change the name of a person who is already grown-up. He has his name on his driving licence and passport and his university certificates which prove that he is a geologist, so he can’t really change it now.

![]()

It was from my dad that I learned what a xenolith is. A xenolith is the name geologists use for a rock which is embedded in another kind of rock. It is a completely different kind of rock even though they are joined together, one inside the other. At first glance it may look like part of the same rock, because it fits inside the rock, but it doesn’t belong there and it doesn’t really match.

And that is me. I am a xenolith, because even though at school I am one of the students, and I am part of my class, and these days I do speak to the other kids in my class and also to some teachers, I am a different kind of person and I am not really like them, and I don’t really fit in.

I looked up the word xenolith online. In Ancient Greek,

xenos

means foreign, and

lithos

means stone, so I am like a foreign stone.

Words

Some people think that because I don’t like to speak much, I don’t like words. That is not true: I do like words, and I know lots of words. That is why I looked up the origin of the word ‘xenolith.’ I like to find out the origin of a word because it gives me a deeper knowledge of that word.

I am writing my own dictionary. My dictionary is not the same as any dictionary you might buy, where they just lump together any words as long as they are in alphabetical order, no matter if those words are interesting or not, or if they have anything in common with each other.

The only words I put in my own dictionary are words which I myself choose, and I only choose them if I like them, or if I need them to describe or to mark something important to me. I use lever-arch files for my dictionary, and that way I can add as many pages as I like because all you do is open the clip and put more pages in.