The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (16 page)

Read The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 Online

Authors: Margaret MacMillan

Tags: #Political Science, #International Relations, #General, #History, #Military, #World War I, #Europe, #Western

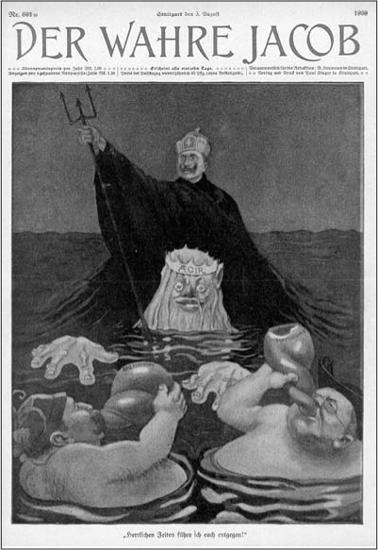

Triumphs abroad were meant to play their part in building the different German states into a strong Reich. Wilhelm was both public and exuberant about his ambitions for Germany and for himself. There would be a New Course in his reign, he told his mother: ‘For ever and ever there will be only one true Emperor in the world and that is the German Kaiser …’

3

And both he and Germany should have commensurate influence around the world. As he said to Eulenburg in 1893: ‘Without being a world figure one was nothing but a poor appearance.’

4

Germany must have a say in the division of the remaining parts of the world which seemed to be up for the taking. ‘In distant areas’, he said in 1900 as he launched a new battleship, ‘no important decision should be taken without Germany and the German Kaiser.’

5

He took to describing himself as ‘the

arbiter mundi

’ – and, of course, of Europe. On his visit to his dying grandmother he assured the new British Foreign Minister, Lord Lansdowne, that ‘I am the balance of power in Europe since the German constitution leaves decisions about foreign policy to me’.

6

The reality, galling to Wilhelm in the first years of his reign, was that Germany’s foreign relations had not been well managed since 1890. Where Bismarck had tried, usually successfully, to keep on good terms with all the other powers, his successors had allowed Germany to drift into one camp, that of the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy. The first costly mistake had been the failure to renew the Reinsurance Treaty with Russia under which each country bound itself to remain neutral if attacked by a third. That it was partly a mistake says something about the indifferent quality of those in charge of Germany’s foreign policy after 1890. The new Chancellor, Leo von Caprivi, was a soldier, and, while intelligent and sensible, he had little background in foreign affairs. He allowed himself to be talked out of renewal by the Foreign Office, in particular by its leading figure, Friedrich von Holstein, who had come to oppose a close friendship with Russia. The result was to encourage the Russians to look elsewhere, in particular to France, with whom Russia signed a secret military agreement in 1894.

4. Heavily influenced by the American naval theorist Alfred Mahan who believed that sea power was the key to world power, Wilhelm II of Germany set out to build his own big navy. He thus set off a costly naval race with Great Britain which in turn helped to persuade the British that they needed to look for allies against Germany.

Moreover what Holstein and his colleagues had hoped for, a rapprochement with Britain, which was on bad terms with both Russia and France, and its closer adherence to the Triple Alliance did not happen. The British already had an understanding with Austria-Hungary and Italy to guarantee the security of the Mediterranean (which largely meant opposing Russian attempts to force the Ottoman Empire to give up control of the crucial passage from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean or French moves to expand their empire). As a result of the lapsing of the Reinsurance Treaty Russia had more to worry about on its frontiers and was less of a threat to British interests in the Mediterranean. Germany also found that its partners in the Triple Alliance grew more assertive as Germany’s position weakened.

It did not help that German policy oscillated in those years between

1890 and 1897 between attempts to win over either Russia or Britain or that German leaders veered back and forth from blandishments and threats. On particular issues, moreover, German policies were too often incoherent. In 1894 Caprivi told the German ambassador in London that the Solomon Islands were of crucial importance to Germany; two months later, Berlin had lost interest.

7

The British were not the only Europeans to find German policies a mystery. It also did not help that the Kaiser, who fancied himself a master diplomat, intervened with increasing frequency and often with disastrous effects. While there is still some dispute about the origins of the Kruger telegram, which he dispatched in 1896 to show support for the Transvaal in the Boer republic’s struggle against Britain, it seems to have been the result of an attempt on the part of his government to prevent him from doing anything worse. (Wilhelm had initially suggested, among other things, establishing a German protectorate over the Transvaal and sending German troops to Africa, which would have a challenging task, given the dominance of British sea power at the time.)

8

In 1897 German policy and governance took a decisive turn which was to push Germany further along the path towards confrontation with Britain. Wilhelm, with the support of Eulenburg and other leading conservatives, decided that the time had come to put his own men into key positions in the German government. Among other changes, he brought back Alfred von Tirpitz, an admiral from the German China squadron, to be his Minister of the Navy and so, as we shall see, set in motion the Anglo-German naval race. And Bernhard von Bülow, the German ambassador in Rome, was summoned to be Foreign Secretary. His impact on German policy was perhaps less dramatic than that of Tirpitz, but he also played a part in the steps that led from peace to war.

Bülow, the man who was supposed to solve Germany’s international problems, was an amusing, charming, cultivated, and clever career diplomat. He was also intensely ambitious and, like his new master, Wilhelm, lazy. ‘He would be quite a fellow’, Bülow’s brother once said, ‘if his character could only attain the height of his personality.’

9

Although the family came originally from Denmark, his father had become the new Germany’s Foreign Secretary in 1873, working loyally as the great Bismarck’s subordinate. Bismarck took a fancy to the son and Bernhard moved steadily upwards in the diplomatic service, cutting

a swathe through Europe’s capitals and making along the way a name for himself as an inveterate ladies’ man. He met his match in his wife, who was the daughter of a leading family in Rome. Although she was married at the time, she divorced her husband, also a German diplomat, and married Bülow, devoting herself to furthering his career.

Over the years, Bülow had gained a deserved reputation among his colleagues for being devious, untrustworthy and slippery as an eel, said Holstein, who initially considered him a friend. ‘Bernhard von Bülow’, wrote Holstein in his diary, ‘is clean-shaven and pasty, with a shifty look and an almost perpetual smile. Intellectually plausible rather than penetrating. He has no ideas in reserve with which to meet all contingencies, but appropriates other people’s ideas and skilfully retails them without acknowledging the source.’

10

Bülow was both adept at making people feel they had said something clever and at giving the impression that he was sharing important information with them. ‘Bernhard makes a secret of everything’, his mother-in-law said. ‘He takes you by the arm, leads you to the window and says: Don’t say anything, but there’s a little dog down there who’s pissing.’

11

He was like a cat, said a woman who knew him, who caught mice by putting out their favourite cheese.

12

From 1897 onwards he turned all his attention to catching his new master. Wilhelm, Bülow assured him repeatedly, was ‘brilliant’, ‘splendid’, ‘completely accurate’, and always said the right thing. It is very difficult to handle the British and requires infinite skill, he told the Kaiser in 1900: ‘But just as the Hohenzollern eagle wiped the two-headed Austrian eagle off the field and clipped the wings of the Gallic cock, so with God’s help and Your Majesty’s strength and wisdom, it will also deal with the English leopard.’

13

Just to reinforce the message, he repeatedly sent fulsome praise of the Kaiser to Eulenburg, no doubt in the knowledge that it would be shown to Wilhelm. ‘Of all the great kings’, Bülow wrote shortly after his appointment, ‘he is by far the most significant Hohenzollern who has ever lived.’

14

He would, he assured the Kaiser himself, be his ‘tool’ and enable him to assert his personal rule over Germany. In 1900 a grateful Wilhelm made him Chancellor.

In the first years, Bülow managed the Kaiser with considerable success. He sent short memoranda spiced up with bits of gossip, avoided formal meetings, where Wilhelm would get bored, and made a habit of going for a walk with him every morning. The von Bülows had Wilhelm

to lunch and dinner and kept him entertained. Nevertheless, Bernhard the Obliging, as one of his critics called him, was prepared to disregard or modify the Kaiser’s wilder policies where he could, especially since the Kaiser often forgot what he had said in the heat of the moment. Nor did Bülow really want to carry out the coup d’état against the German parliamentary institutions which the Kaiser so wished for. What he wanted to do was manage the German people as well as their ruler and, as much as possible, bridge their differences. His policy, then and when he later became Chancellor, was one strongly promoted by Wilhelm and his conservative advisers of bringing together German nationalist and conservative forces in support of the crown and at the same time undermining the growing socialist movement and the strong regional feelings, in the south for example, which had never really accepted Prussian rule.

Sammlungspolitik

, as it was known, needed a core organising principle and this was to be pride in Germany. The government, Bülow believed, must adopt ‘a courageous and generous policy that knows how to uphold the joy in the present character of [our] national life, a policy that mobilizes national energies, a policy attracting the numerous and ever-growing

Mittelstand

[middle class]’.

15

An active foreign policy was clearly crucial in doing this. The fuss over Samoa, Bülow said revealingly, ‘has absolutely no material, but an ideal and patriotic interest for us’. And he gave orders that German newspapers were to treat the issue in such a way as ‘strengthens the trust in our foreign policy internally’.

16

His key strategy in foreign affairs was to manoeuvre to ensure that Germany continued to rise up the table of world powers. That might well mean stirring up conflict among the other nations. In 1895 he had told Eulenburg: ‘I consider an Anglo-Russian collision not as a tragedy but as “an aim most fervently to be desired”.’

17

Let the two of them exhaust themselves while Germany quietly grew stronger.

As far as specific policies went, Bülow believed in maintaining the Triple Alliance with Austria-Hungary and Italy and was privately cool on the idea of an agreement with Britain. Much better for Germany, he felt, to remain neutral between Britain and Russia in their continuing conflict. ‘We must hold ourselves independent between the two’, he wrote, ‘and be the tongue on the balance, not the pendulum oscillating to and fro.’

18

If he inclined to either side, it was probably towards Russia,

which he felt in the longer run was likely to be the stronger of the two powers. As for Britain, he held that sooner or later it would realise that it had to be on friendly terms with Germany because of British enmity with both Russia and France. It never seems to have occurred to him that the British might come up with other solutions to their isolation.

In directing Germany’s foreign policy he had the support, at least initially, of one of the Foreign Ministry’s cleverest, most powerful, and strangest figures, Friedrich von Holstein of the Political Division. Eulenburg called Holstein ‘the Monster of the Labyrinth’ and the name has stuck. The epithet was unfair because Holstein was no monster but a highly intelligent and dedicated servant of the German state who did his best to further its interests internationally. Like all nicknames, though, it had an element of truth. He was secretive and saw conspiracies everywhere. Bismarck’s son Herbert described him as having ‘an almost pathological delusion of persecution’.

19

While Holstein could be cruel and cutting to others, he was himself highly sensitive. He lived extremely simply in three small and unpretentious rooms and, apart from target shooting, seemed to have had no other interests beyond his work. He rarely went out in society and did his best to avoid meeting the Kaiser, of whom he increasingly disapproved. When the Kaiser tried to drop by the Wilhelmstrasse to meet Holstein, the latter disappeared on a long walk.

20

When the two men finally met in 1904 at a large dinner, it is said that they talked about duck hunting.

21

Holstein always refused the highest offices within the Wilhelm-strasse, preferring to be the power behind the scenes, keeping track of the reports coming in and out, spinning his intrigues and rewarding friends and punishing his enemies. His office adjoined that of the Foreign Secretary and he developed the habit of wandering in through the door whenever he pleased. Although he had been close to Bismarck, who relied heavily upon him, he fell out with the old Chancellor, his son, and his supporters primarily over the issue of Russia. Holstein opposed the Reinsurance Treaty and the very idea that Germany and Russia could build a friendship. Perhaps because he had thoroughly disliked his time as a young diplomat in St Petersburg, then the capital of Russia, his hatred and fear of Russia was one of the few consistent strands in his foreign policy.

22

In time he and Bülow would part company over the same issue.