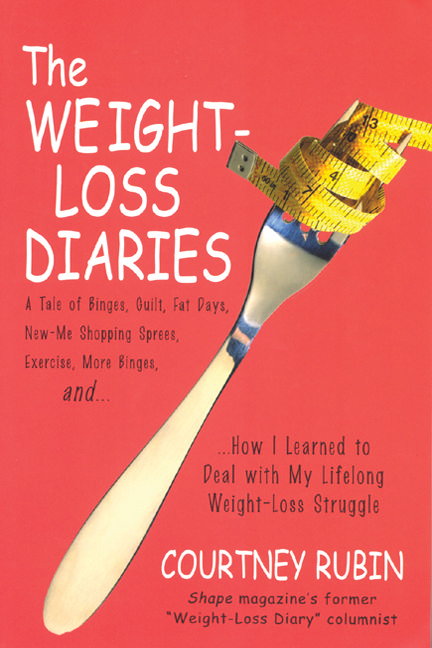

The Weight-loss Diaries

Read The Weight-loss Diaries Online

Authors: Courtney Rubin

COURTNEY RUBIN

Copyright © 2004 by Courtney Rubin. All rights reserved. Manufactured in the United States of

America. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication

may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval

system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

0-07-144273-1

The material in this eBook also appears in the print version of this title: 0-07-141623-4.

All trademarks are trademarks of their respective owners. Rather than put a trademark symbol after

every occurrence of a trademarked name, we use names in an editorial fashion only, and to the benefit

of the trademark owner, with no intention of infringement of the trademark. Where such designations

appear in this book, they have been printed with initial caps.

McGraw-Hill eBooks are available at special quantity discounts to use as premiums and sales

promotions, or for use in corporate training programs. For more information, please contact George

Hoare, Special Sales, at [email protected] or (212) 904-4069.

TERMS OF USE

This is a copyrighted work and The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. (“McGraw-Hill”) and its licensors

reserve all rights in and to the work. Use of this work is subject to these terms. Except as permitted

under the Copyright Act of 1976 and the right to store and retrieve one copy of the work, you may not

decompile, disassemble, reverse engineer, reproduce, modify, create derivative works based upon,

transmit, distribute, disseminate, sell, publish or sublicense the work or any part of it without McGraw-Hill’s prior consent. You may use the work for your own noncommercial and personal use; any other

use of the work is strictly prohibited. Your right to use the work may be terminated if you fail to comply

with these terms.

THE WORK IS PROVIDED “AS IS.” McGRAW-HILL AND ITS LICENSORS MAKE NO GUARANTEES OR

WARRANTIES AS TO THE ACCURACY, ADEQUACY OR COMPLETENESS OF OR RESULTS TO BE OBTAINED

FROM USING THE WORK, INCLUDING ANY INFORMATION THAT CAN BE ACCESSED THROUGH THE WORK

VIA HYPERLINK OR OTHERWISE, AND EXPRESSLY DISCLAIM ANY WARRANTY, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED,

INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A

PARTICULAR PURPOSE. McGraw-Hill and its licensors do not warrant or guarantee that the functions

contained in the work will meet your requirements or that its operation will be uninterrupted or error

free. Neither McGraw-Hill nor its licensors shall be liable to you or anyone else for any inaccuracy, error

or omission, regardless of cause, in the work or for any damages resulting therefrom. McGraw-Hill has

no responsibility for the content of any information accessed through the work. Under no

circumstances shall McGraw-Hill and/or its licensors be liable for any indirect, incidental, special,

punitive, consequential or similar damages that result from the use of or inability to use the work, even

if any of them has been advised of the possibility of such damages. This limitation of liability shall

apply to any claim or cause whatsoever whether such claim or cause arises in contract, tort or

otherwise.

������������

Want to learn more?

We hope you enjoy this

McGraw-Hill eBook! If

you’d like more information about this book,

its author, or related books and websites,

For my mother

In memory of some fine Fines: my grandpa Irving and

my uncle Dennis

And especially for my grandmother Ruth Fine

This page intentionally left blank.

Introduction

In the fourteen years since my first successful diet—at age fourteen—I’ve lost and gained more than 350 pounds.

Some people have tried every kind of diet—Weight Watchers, Atkins, grapefruit, Zone, Sugar Busters—and I have, too. I’ve usually lasted about three days on each. My big weight losses—thirty-five pounds, forty pounds, fifty pounds—were usually on diets of my own devising: either extremely low calorie or extremely low fat, the latter of which was introduced to me by my freshman-year college roommate. (Emily was also the one who introduced me to the concept of exercise, but we’ll get to that later.)

I’m good at starting a diet. I even like it. Actually, it’s the prospect of starting that I love, the same way I savor the prospect of a first date. Since he hasn’t yet popped a zit at the table, calculated how much of the paella I’ve eaten and then split the bill accordingly, or just plain not called again, I’m free to daydream about the way things could unfold. The regrets and disappointments of relationships past dissolve in a flurry of what-should-I-wear?

and what-if-he-doesn’t-show-up? and the possibility that maybe, just maybe, this date might be good.

Usually it isn’t. The thrill of the new wears off fast.

The same with starting diets. In my teens I would read every “Lose Ten Pounds with Four Simple Changes” article I could find, reread

The Woman

Doctor’s Diet for Teenage Girls

(the first diet book I ever owned), page through

Seventeen

magazine dreaming about the clothing I’d finally be able to buy, and make elaborate plans about what I would and wouldn’t eat. It was really only about food then, because in those days, the eighties, gym memberships were mostly still for the neighborhood health nuts, and besides, the idea of exercising in public seemed too humiliating. I was always secretive about my v

Copyright © 2004 by Courtney Rubin. Click here for terms of use.

vi

Introduction

plans—for me, my dreams and diets were as delicate and fragile as bubbles, ready to pop at the slightest raise of an eyebrow from anyone. So I’d wake up early (and without an alarm clock) the morning I was going to start—

always ravenous, but also brimming with resolve and the pleasure of my secret.

I was never quite sure when I’d start telling people about my diet. Preferably they’d just start noticing as the weight fell away. It didn’t matter, though, because I never got that far. I’d make it until after school on Day 1 of the diet and the munchies would start. Or I’d make it through three days and my family would go out to dinner and I’d give in. Or no big diet-busting thing in particular would happen, but by Day 5 or 6 I’d have had it with struggling every hour; thoughts of food blotting out nearly everything else. I’d think about all the days that stretched ahead of me—days without oatmeal-raisin cookies or full-fat cheese—and give up. And of course, I’d start eating everything I’d forbidden myself, thinking:

Tomorrow I’ll start. Definitely tomorrow

.

My successful diets worked because they worked relatively fast. I wanted to be thin, and in my typically impatient, nothing-caffeine-and-an-all-nighter-can’t-solve mentality, I wanted to get the job done as quickly as possible. So that meant unrealistic, punishing regimens of an hour of exercise and 750

calories a day—regimens that drove me straight to the bakery counter before long. The diet camp I went to at age fourteen—my first successful diet, bankrolled by my grandmother—I’d chosen specifically because its success stories seemed to have lost the most pounds. (I quickly gained back the weight I’d lost when I returned home to unrestricted access to the refrigerator and no enforced aerobics classes.)

For as long as I can remember, I’ve fought, with varying degrees of success, two battles—one with my weight and the other with my family about my weight. Most people don’t have the idealized version of themselves staring them in the face, but I do: I’m half of a set of fraternal twin sisters, and for years Diana could eat so much yet stay so slim that my parents used to joke that she had a hollow leg. For the past five years or so, even she has had to watch herself, but that’s not much consolation.

Eating has consumed my life for years. I was bingeing (which differs from plain pigging out or overeating in that it is frantic and frenzied and out of control, and for me usually involved going to at least three stores to buy all the food I wanted because I was too embarrassed to buy it in one). I was starving. I was dieting. I was wishing I could have the willpower to stay on a diet.

Introduction

vii

Not a day went by that I didn’t think life would be better or easier if I were thinner.

My diet pattern—either three days here and three days there, or lose forty pounds, fall off the diet with a spectacular crash, and then gain sixty—

changed in the fall of 1998 when I was twenty-three. I began my usual starvation diet in September, right after Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement. The day of fasting required by Jewish law was the perfect way to start a diet—or so I’d been hearing all my life from my grandmother. I got a new gym membership card—it had been so long since I’d used mine that I’d lost the old one—and started a rigid regimen of hour-long workouts five days a week.

I got twelve pounds into the diet. I was heavy enough at the time that this was just enough weight for me to feel tantalizingly close to actually

seeing

results, but certainly not enough for anyone else to see them. Then I ate four chocolate-chip cookies at a coworker’s birthday party. Ditching the Lean Cuisines and egg-white omelets immediately followed. But a funny thing happened: I decided to keep going to the gym anyway. I was tired of my life—tired of feeling out of control, tired of remembering major events based on what size I wore and what I had or had not eaten, tired of my pants being too tight—and not sure what else to do. Fitting in workouts somehow seemed more manageable than completely revamping my eating, something I’d failed at so miserably so many times. I had a good fifty pounds to lose, so I didn’t really expect that I could lose them with a few hours a week of stationary biking or walking around the track. But maybe, just maybe, a miracle would happen.