The White Goddess (48 page)

Authors: Robert Graves

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Mythology, #Literature, #20th Century, #Britain, #Literary Studies, #Amazon.com, #Mysticism, #Retail

Here the trees are those of O’Flaherty’s Beth-Luis-Nion, without the intrusion of arbutus, elm, white-hazel and the rest. The unnamed ‘shrub trees’ evidently include the elder, reed or water-elder, broom and woodbine. This arrangement according to nobility is eccentric – the apple-tree and holly being excluded from chieftainship – and is possibly connected with the Greek 24-letter alphabet rather than with the Ogham 20-letter one or its 25-letter expansion.

The subject is very difficult, and the Irish ollaves had no interest in making it plain to outsiders.

1

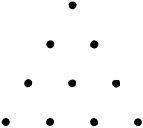

It is likely that Gwion was also aware of the value given to the number Five by the Pythagoreans and their successors. The Pythagoreans swore their oaths on the ‘holy tetractys’, a figure consisting of ten dots arranged in a pyramid, thus:

The top dot represented position; the two dots below, extension; the three dots below those, surface; the four dots at the bottom, three-dimensional space. The pyramid, the most ancient emblem of the Triple Goddess, was philosophically interpreted as Beginning, Prime and End; and the central dot of this figure makes a five with each of the four dots of the sides. Five represented the colour and variety which nature gives to three-dimensional space, and which are apprehended by the five senses, technically called ‘the wood’ – a quincunx of five trees; this coloured various world was held to be formed by five elements – earth, air, fire, water and the quintessence or soul; and these elements in turn corresponded with seasons. Symbolic values were also given to the numerals from 6 to 10, which was the number of perfection. The tetractys could be interpreted in many other ways: for instance, as the three points of the triangle enclosing a hexagon of dots – six being the number of life – with a central dot increasing this to seven, technically known as ‘Athene’, the number of intelligence, health and light.

1

To judge from a design on a glass dish of the Seleucid epoch, showing the façade of Solomon’s Temple as rebuilt by Zerubbabel on the original Phoenician model, the spirally fluted pillars correspond with Boaz, Solomon’s right-hand pillar dedicated to growth and the waxing sun; the vertically fluted with Jachin, his left-hand pillar dedicated to decay and the waning sun. The symbolism became confused when the Jews made their New Year correspond with the autumn vintage festival, for the pillars were then referred to as Jachin and Boaz, not Boaz and Jachin, but the tradition remained ‘Boaz is to Jachin as Gerizim is to Ebal – as blessing is to cursing’. Gerizim and Ebal were the twin peaks covering the Ephraimite shrine of Shechem. Gerizim was on the right-hand as one faced east from Shechem, Ebal on the left, and Shechem was a home of the terebinth cult. In

Deuteronomy

XI

,

29 there is a prophecy attributed to Moses. ‘You shall put the blessing upon Gerizim and the curse upon Ebal …towards the entrance into Shechem where dwell the Canaanites in the towered house beside the sacred terebinth of Moreh.’

This was as it should have been. The terebinth, the hard-wooded Canaanite equivalent of Duir the oak, was naturally placed in the middle with Ebal on the unlucky left, Gerizim on the lucky right.

1

At Arles, in Provence, the cult of the Goddess as a Triad or Pentad of Mothers has survived under Christian disguise until today, when her festival is celebrated from May 24th to May 28th, the middle of the Hawthorn, or Chastity, month, but now her devotees are largely gipsies. As a Triad she has become known as ‘The Three Maries of Provence’ or ‘The Three Maries of the Sea’; as a Pentad she has had Martha added to her company, and an apocryphal serving-girl called Sara. It seems that these were Christianizations of pre-Christian reliefs on the tombstones of the cemetery of Alyscamps at Arles, in which the Triad, or Pentad, was shown on one panel; and below, on another, the soul in resurrection. The scene was explained as the Raising of Lazarus. As late as the time of Dante the cemetery was used in the ancient style. The corpse was laid in a boat, with money in it, called

drue

de

mourtilage

and floated down the Rhône to the Alyscamps. The name Alyscamps has been explained as

Campi

Elysiani

,

‘the Elysian Fields’, but it is as likely that Alys was the ancient name of the Goddess; it may even be that the Homeric adjective Elysian (the

e

is a long one) is derived from her name. Alys also appears as

alise

or

alis

in many French place-names. Dauzat’s

Dictionnaire

Etymologique

,

under

alis

,

alise

,

meaning a ‘sheltered creek’, derives it from ‘the Gaulish word

alisia

,

perhaps pre-Celtic, which is represented by numerous place-names, and which must also have provided the Spanish word for alder,

alisa

.’

This makes good mythical sense, because Calypso’s sepulchral island of Ogygia was screened by alder thickets. Alys or Alis or Halys is the name of the biggest river of Asia Minor, and that it is pre-Hellenic is shown by the town of Aliassus (

-assus

is a Cretan termination) built on its banks just before it turns north to empty into the Southern Black Sea. There are also two Hales rivers, one in Ionia, the other in Lucania, which may be named after the same goddess. One name for the alder in German is

else

,

corresponding with the Scandinavian word

elle.

The Danish

Ellerkonge

is the alder-king, Bran, who carries off children to the other world; but

elle

also means ‘elf’ which should be regarded as a

clethrad

,

or alder-fairy. Thus in Goethe’s well-known ballad, based on his predecessor Herder’s

Stimmen

der

Völker

,

Ellerkonge is correctly translated ‘Erlkönig’, the commoner German word for alder being

erle.

1

Sed

manendum,

tum

ist

a

aut

populina fors

aut

abiegina

est

tua.

(Act II.)

1

British sailors used always to be tattooed with a star in the hollow of the hand between the thumb and fore-finger, and the custom survives in some ports. This is originally a plea to Venus as Goddess of the Sea and Jupiter as God of the Air to bring the sailor safe ashore, the star being the symbol of hope and guidance.

1

Another five-pointed leaf in sacral use was the cinquefoil, a chief ingredient in the flying ointment used by mediaeval French witches. An alternative in one formula is the poplar leaf, doubtless the five-pointed sort. Like the fleur-de-luce used in the same ointment – apparently because of its three-petalled flower and its red seeds contained in a triangular seed-box – it has no toxic effect, but seems to have been introduced in the Goddess’s honour (with a thickening of soot and oil, or infant’s fat) to enhance the effect of the other ingredients: namely, the abortificent parsley, bat’s blood to assist nocturnal flight, and the highly toxic aconite, belladonna, hemlock and cowbane. The formulas are quoted in Miss M. Murray’s

The

Witch

Cult

in

Western

Europe.

Mr. Trevor Furze has supplied me with two further formulas of English origin: (1) The fat of a newly-born infant;

eleoselinum

(wild celery, also called ‘smallage’, or ‘water-parsley’, a mediaeval remedy against cramps); skiwet (wild parsnip, the leaves of which were regarded as poisonous but used in poulticing); soot. (2) Bat’s blood, to be obtained at the wake of the new moon; pentphyllon (cinquefoil) poplar leaves; soot. Perhaps the ‘parsley’ in the French formula is really water-parsley, introduced to protect the witches against cramps when flying.

1

At Rome in the second century

BC

a sacred grove could be felled at an even cheaper rate: the sacrifice of a single pig. Cato the Censor in his

De

Re

Rustica

quotes the prayer of placation that the timber-hungry farmer must offer to the deity concerned.

1

Evidently a mistake for holly.

Chapter Twelve

I suggest in the first part of this argument that the ‘I am’ and ‘I have been’ sequences frequent in ancient Welsh and Irish poetry are all variants of the same calendar theme. Here, for instance, is the ‘Song of Amergin’ (or Amorgen) said to have been chanted by the chief bard of the Milesian invaders, as he set his foot on the soil of Ireland, in the year of the world 2736 (1268

BC

). Unfortunately the version which survives is only a translation into colloquial Irish from the Old Goidelic. Dr. Macalister pronounces it ‘a pantheistic conception of a Universe where godhead is everywhere and omnipotent’ and suggests that it was a liturgical hymn of as wide a currency as, say, the opening chapters of the

Koran,

or the Apostles’ Creed. He writes: ‘Was it of this hymn, or of what he had been told of the contents of this hymn, that Caesar was thinking when he wrote: “The Druids teach of the stars and their motions, the world, the size of lands, natural philosophy and the nature of the gods”?’ He notes that the same piece ‘in a garbled form’ is put into the mouth of the Child-bard Taliesin when narrating his transformations in previous existences. Sir John Rhys pointed out in his

Hibbert

Lectures

that many of Gwion’s ‘I have been’s’ imply ‘not actual transformation but mere likeness, through a primitive formation of a predicate without the aid of a particle corresponding to such a word as “like”.’

The

Song

of

Amergin

begins with thirteen statements, provided with mediaeval glosses. The thirteen statements are followed by six questions, also provided with glosses. These are followed in Professor John MacNeill’s version by an

envoie

in which the Druid advises the People of the Sea to invoke the poet of the sacred rath to give them a poem. He himself will supply the poet with the necessary material, and together they will compose an incantation.

| T HE S ONG OF A MERGIN | |

| God speaks and says: | Glosses |

| I am a wind of the sea, | for depth |

| I am a wave of the sea, | for weight |

| I am a sound of the sea, | for horror |

| I am an ox of seven fights, | for strength |

| or I am stag of seven tines, | |

| I am a griffon on a cliff, | for deftness |

| or I am a hawk on a cliff, | |

| I am a tear of the sun, | ‘a dew-drop ’ – for clearness |

| I am fair among flowers, | |

| I am a boar, | for valour |

| I am a salmon in a pool, | ‘the pools of knowledge’ |

| I am a lake on a plain, | for extent |

| I am a hill of poetry, | ‘and knowledge ’ |

| I am a battle-waging spear, | |

| I am a god who forms fire for a head. | [ i.e. ‘gives inspiration: Macalister] |

| or I am a god who forms smoke from sacred fire for a head. | ‘to slay therewith ’ |

***

| 1. | Who makes clear the ruggedness of the mountains? or Who but myself knows the assemblies of the dolmen-house on the mountain of Slieve Mis? | ‘Who but myself will resolve every question?’ |

| 2. | Who but myself knows where the sun shall set? | |

| 3. | Who foretells the ages of the moon? | |

| 4. | Who brings the cattle from the House of Tethra and segregates them? | [ i.e. ‘the fish ’, Macalister, i.e. ‘the stars’, MacNeill] |

| 5. | On whom do the cattle of Tethra smile? or For whom but me will the fish of the laughing ocean be making welcome? | |

| 6. | Who shapes weapons from hill to hill? | ‘wave to wave, letter to letter, point to point’ |